After the Dutch Protestants booted (or clogged) the Spanish Catholics out of the Netherlands in the 17th Century, Holland became a world power, hitting the high seas in its well-built ships to trade textiles and cheeses for exotic goodies from parts newly known. Dutch paintings were part of the industry—those that weren’t bought by the citizens of Amsterdam and Leiden were traded like rugs or pottery. A lot of the leisure time afforded by the surplus wealth went into the production and promotion of these paintings, as it had in Italy two centuries before (and in ancient Roman times before that), and as it would in France two centuries hence.

Some of those paintings have ended up in the houses of fortunate Boston collectors, who perhaps have in common with the Dutch capitalists a thrifty appreciation of opulence. (Could the white-ruffed, rosy-cheeked, art-loving folks in Rembrandt’s great portraits of the period be substituted with Cabots and Lodges, Mugars and Raabs, in suits and nice dresses?) Most of us will never know who those collectors are—only that they have loaned us a look at the great paintings they have at home, on view through mid-September at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, in The Poetry of Everyday Life: Dutch Paintings in Boston Collections.

The captions won’t tell us who loaned the paintings. But we’re free to imagine the moneyed matrons and patrons of Beacon Hill and Wellesley supervising the transportation, by steady-handed MFA movers, of Jan Baptist Weenix’s portrait of The De Kempenaer Family. (Those three young girls stopping to pose, as if for a snapshot, with their warm-eyed mother on the terrace of their palace—the youngest with a doll, another pushing a custom-crafted baby carriage—might put us in mind of Sargent’s Boit girls and of Velasquez’s royal Spanish families.) We may also imagine that the owners hang the painting above the mantel in the drawing room of their mansion, protecting it in a glass frame from the hot and sooty hearth.

Turning from the De Kempenaers, we can take our time puzzling over the motley assortment of paintings in the loosely categorized “figures” section of the exhibition, but will there be time to give each picture the attention it requires? (Will we make it to the adjacent “landscapes” section within the hour, for example, and still have time for our own creative weekend projects?) There’s the unmistakably Rembrandt painting, The Apostle James Major, that we’ve seen before, like the caption says, at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Mottled, modest, alive, and luminous, there is no intricate arrangement of interesting props to contemplate here, just a heavy-hearted sage praying outdoors in his brown robe.

But here’s a huge painting of war goddess Minerva (by Arie de Vois) in plumed helmet, black metal breastplates, embroidered red robe, and outrageously frivolous slippers, standing haughtily, her lance planted beside her, before the nine voluptuous muses she has come to see near a waterfall on Mt. Helicon. How can we stand before this large, colorful work of barely restrained gaudiness long enough, gazing in mock rapture at the indolent muses in all their particular detail, when we know that we will want to look with great care at the several small slice-of-life paintings that wait for us on the wall nearby? We need to take a deep breath and appreciate the muses singing, playing the lute and the flute, and doing geography on a globe before we move along to the portraits.

The paintings on the nearby wall will still be there when we’re ready. The artist will still be giving a drawing lesson to his student. The old violist will still be ruminating alone in an open cafe window. (And we’ll still be able to see, in interior shadow from the back, our favorite detail of the whole exhibit: the woman in the white bonnet eating lunch at a table.) The surgeon on a house call will be performing a foot operation on an injured hunter when we arrive—and the hunter will be taking it like a true stoic, his wall proudly adorned with a stuffed souvenir crocodile and a hooked harpoon.

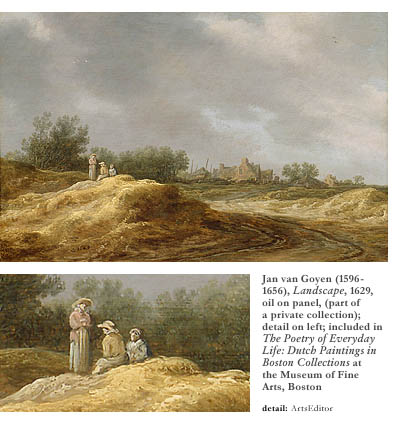

It has been four hundred years since the steady-eyed Dutch painters went outside with their easels and took a long look at their land and sky. (Shakespeare was being his bawdy self in London, and the pilgrims were landing artlessly at Plimouth.) The sun apparently was rarely shining in the yellowish, diluted orange, or blue-gray sky of the Netherlands. But that didn’t stop the landscape paintings from being rich with detail—rivers flowing helpfully through flat landscapes; plumes of smoke curling from the chimneys of thatched cottages; a boxy cart moving slowly along a path (which compositionally holds the picture together) and around small sand dunes toward the steepled town in the distance; people getting into or out of boats (among them, a man on shore gesturing to his companion with the oars: our second favorite detail) or gathering to rest from planting barley on a knoll beside the field. Four hundred years, and still the sea has not managed to break through the dikes and flood those paintings. For the most part they were done below sea level, like everything in Holland, and not imagined from classical scenes in Italian landscapes, which gives them the grave majesty that we see in Rembrandt’s portraits and Biblical scenes.

Whether we’re philanthropic Bostonian collectors, armchair art historians noting the Dutch influence on the rurally sympathetic 19th Century French paintings of Corot and Millet and their Impressionist descendants, or just contentious bums intent on traveling four hundred years into the past just to get away from it all, we’re liable to wonder whether we like better a flatland painting like Jan van Goyen’s Landscape (perhaps taken from the wall above the brass-fixtured toilet) or Jacob van Ruisdael’s Wooded River Landscape with Shepherd (maybe taken from its place beside the beveled Italian Renaissance mirror in the hall). Aren’t van Ruisdael’s sweeping landscapes, translated from the Italian, absolutely wonderful, all full of the sound of crashing symbols, and yet by now also a little melodramatic? The shepherd leading his flock down the hill; the lightning-stricken trees in the foreground pointing out the sky and the mountainous distant horizon; the unharnessed stream galloping diagonally across the huge canvas—the enormity of the picture! Maybe we don’t love it intimately like we do the woman in the white apron standing by her cottage with a basket. But we could practically take a leap right into the van Ruisdael picture and disappear forever.

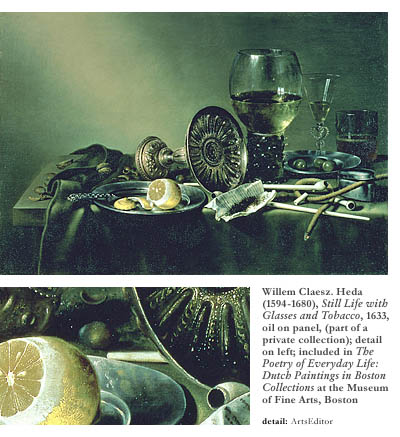

We could meet the shepherd for a roemer of ale and a good laugh back at his thatched cottage (which doesn’t appear in the picture). Sleeping overnight (the last cart leaves for Haarlem at five), we could set up an easel in the morning and do a little still-life painting while he went off with the flock. Apparently that (people painting pictures) would not have surprised an industrious 17th Century Dutch peasant the way it might a 21st Century mass-produced American. Our picture, though, wouldn’t look much like the paintings in the smaller, darker room of the Torf Gallery—Willem Claez. Heda’s Still Life with Glasses and Tobacco (taken down from a dining room wall in Manchester-by-the-Sea, probably), Balthasar van der Ast’s Still Life with Fruit and Shells, or Pieter Claesz.’s Still Life with Peacock Pie. Though the peasants would have been familiar with the flies and mice that feast on the decaying foods in these virtuosic pieces, they would not have been likely to have imported lemons, pewter dishware, Italian wineglasses, and fresh-killed peacocks on hand. And we don’t necessarily know how to do still-life paintings anyway.