When Pamela Sienna conceived the series of “wrapped package” paintings that she continues to work on three years later, she didn’t have access to live images of the nuclear explosions she wanted to depict in the background. They weren’t available for plein aire landscape paintings outside the window of her East Boston studio. She hadn’t been around for the nuking of Hiroshima in the ’40s. The Cuban Missile Crisis in the early ’60s hadn’t produced the blast (aw, shucks!) that she might have been able to use images from. And pictures of Three Mile Island trembling and Chernobyl leaking wouldn’t do for the cataclysmic effect she desired.

By the time Sienna got around to doing her immaculate, illusionist, anti-nuke paintings, the nuclear clock had been turned back an hour or two, thanks to the defenestration of the Iron Curtain. But the threat of nuclear warfare still loomed in the figurative background of all global affairs, as it has since the Manhattan Project brought us the strange fruit of Einstein’s research in physics, and Sienna saw no reason to forget about it. Even given the increase in tension likely to be created by the war about Iraq, no one knows whether another nuclear bomb will ever detonate, and if it does, whether it will be by a developing-world despot or a world-war monger.

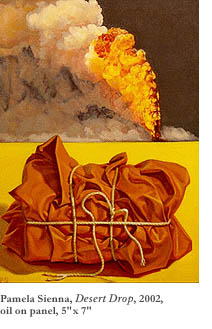

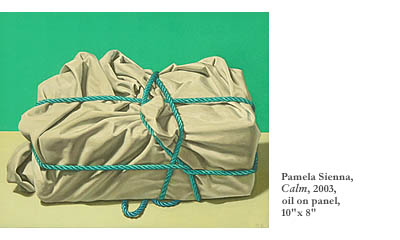

A believer in Yeats’ observation that a work of art is the social act of a solitary person, Sienna wanted to keep the issue on the proverbial radar screen by juxtaposing, in multiple but various treatments of the scene, a paradoxically beautiful image of the iconographic nuclear blast (not always your typical mushroom cloud) with the equally symbolic yet more mysterious image of a wrapped package on the unblemished plane of bright color in the foreground. To get the best images, she went right to the source—not to Pakistan, China, North Korea, or Russia, but to the largest manufacturer of weaponry in the world. The U.S. Department of Energy, obliged by the Freedom of Information Act to provide images from the roughly 900 bomb tests done in the western deserts from the early 1950s to the mid-1970s, complied with her request.

A believer in Yeats’ observation that a work of art is the social act of a solitary person, Sienna wanted to keep the issue on the proverbial radar screen by juxtaposing, in multiple but various treatments of the scene, a paradoxically beautiful image of the iconographic nuclear blast (not always your typical mushroom cloud) with the equally symbolic yet more mysterious image of a wrapped package on the unblemished plane of bright color in the foreground. To get the best images, she went right to the source—not to Pakistan, China, North Korea, or Russia, but to the largest manufacturer of weaponry in the world. The U.S. Department of Energy, obliged by the Freedom of Information Act to provide images from the roughly 900 bomb tests done in the western deserts from the early 1950s to the mid-1970s, complied with her request.

“I was brought up in the age of atomic anxiety,” says Sienna of her current preoccupation. Unlike some baby-boom-generation artists, this representational but not quite realist painter has never found solace for that anxiety in abstraction (what she calls “the part of the painting process that takes just the first couple of hours” in a serious painter’s effort to “say something”). Nor does she speak glowingly of painting that’s “less about painting than it is about theory or concepts based on concepts.” A hard-working craftsperson who acknowledges that it takes years to learn how to paint in the vivid representational style she loves, she derides trends toward the frivolous in the art world, including glitzy glass architectural wonders built for installation artists and “the same 20 painters you see in all the other museums.” And she says of those who declared painting dead in the 1990s: “They weren’t looking!”

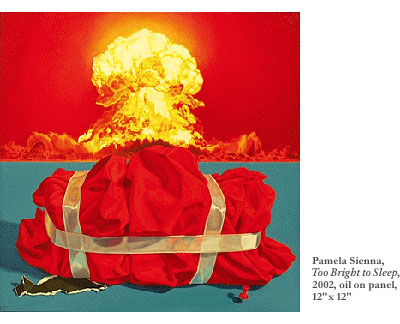

It is evident from a glance at Sienna’s symbolically loaded paintings (inspired in part by the wrapped packages and eerie realism of Chilean artist Claudio Bravo) that they require a great deal of labor and a very steady hand. In the late-night solitude of her studio, she applies—one at a time, with small brushes—the 15 or 20 layers of glaze (paint diluted with linseed oil) that add up to a single painting, eventually achieving the transparent yet brilliantly colorful effect you get “from looking at a ruby and seeing the light bounce through it in reaction with light in the atmosphere.” Sienna’s background images of nuclear explosions, deadly and luminous formations of yellow and red flame, sometimes fringed by coils, rolls, blankets, plumes, or billowing pillows of white or gray smoke, can take the shape of a flower, a helmet, a screw, or the legendary mushroom. By themselves on the hardboard panels, the fires would be impressive illusionist paintings worth a bit of comparison and contrast on their own. But the placement of the mysterious gift in the foreground provides an element of cryptic mystery that doubles the attention.

Is the nuclear fire a thing of beauty forever? Is the generous gift actually something as deadly as the nuclear fire? Which connotation of the symbol should we settle on?

These jeopardizing questions are presented in clear, visually symbolic language in all four of the paintings that the Arden Gallery, at 129 Newbury Street in Boston, displays in its small rear showroom with the works of its other artists. In Last Possession, the draped and bundled gift lies not quite squarely in the foreground of the picture on the dark red desert-like plane that recedes even more darkly to the horizon. A cream-colored cloth textured with as many curious creases and folds as the coat of a soldier in a Caravaggio painting or a tablecloth in a Dutch still life, and tied up loosely in a loopy length of braided red rope that itself demands admiration, the package simultaneously invites and resists interpretation, attracts and repels the hand drawn to its trompe l’oeil temptation. The blank sky above the razor’s-edge horizon sets off the dragon-red furls of flame that come to a head in a brilliant ball of yellow flame. In the luxuriously draped bundle there may be the attaché case of a Rumsfeldian defense monster—er, minister—who can deny with a straight face that the war about Iraq has anything to do with oil interests. Or perhaps it merely contains a child’s suitcase full of pastel cotton clothing.

There’s no telling—and Pamela Sienna, as private in person as the packages in the paintings, isn’t saying, even if she knows—what’s in the slightly lumpier rectangular shape concealed by a startling red drapery in Too Bright to Sleep. Whatever ominous or gentle gift rests on the blue plane that takes up the lower half of the picture plane, no one is likely to emerge from the volcanic cone of yellow flame on the horizon (under a deep red sky) to cut the translucent ribbon that Sienna has gone to the somewhat sinister trouble of wrapping it with. A red thumbtack stuck in the foreground throws a dark shadow toward the package, and a scrap of paper blackened by the fire beckons the imagination. The lumpy concealed shape could belong to one of the many desert creatures who no doubt lost their lives to nuclear testing before the organizers were forced to go underground (literally) with their tests in the ’70s—a covey of roadrunners, a single coyote, or a human child dead of leukemia. Though it’s a completely lifeless blue landscape (not the purplish-brown or yellowish-red or greenish-beige of a real desert), the package could even be a desert plant Sienna’s shielded from the blast in a symbolically protective act. A yucca plant, maybe. A clipped-back maguey cactus, perhaps.

The Arden Gallery, under the ownership of Hope Arden Turner, has represented Sienna’s pretty, apocalyptic work for three years, apparently since she began to gift-wrap these ominous packages. In addition to the packages, the gallery sells the remaining few unsold results of Sienna’s 1994 series 27 Paintings of Bodies and Bombs—unabashedly unsubtle juxtapositions of nudes and nukes instead of gifts and nukes. These include at least two small paintings of Joseph R. McCarthy, the notorious United States senator who conducted hearings in the 1950s targeted at those whom he classified as Communists. Pamela Sienna has placed herself next to the senator in one of the paintings, depicting herself as a toddler of the times looking up at the kind of black-and-white television that broadcast the hearings. Sitting on the floor, she’s wearing a blue dress and white socks against a deep red background that concurrently alludes to “red” Communism and the first color of the American flag. She’s home alone in that social context, a child who’ll be taught to unwrap her first concealed gifts soon, unaware quite yet of the role her country is playing in the world.