A grown man bounds onstage in a dress to cheers and applause. A sinister figure appears from the left to a lively chorus of boos and hisses. A young woman playing the part of boy hero slaps her thigh to show off her shapely legs. A band of ragtag characters fights for the good, right, and true with a handful of bad puns along the way. This is the British Pantomime, a widespread and well-loved theatrical tradition in the United Kingdom, seen rarely here in the States. But never fear—one company is keeping the tradition alive in the Boston area. Matthew Woods, artistic director of the physical theatre troupe Imaginary Beasts, has produced a Panto each winter for the past eight years.

Woods urges those who have never seen one to forget their preconceived notions about Pantomime. “Marcel Marceau’s white face? Story filler for a ballet? An evening of charades?” he asks. “You will find none of the above in the traditional British Panto.” A lot of people think of Pantomime as “acting without words,” says Woods, but this is an incorrect assumption. Historically, the development of the British Pantomime was sparked by limits imposed by the court on amateur theatrical houses. These troupes were seen as competition for the court-sanctioned houses, and as a result were not allowed to produce works with spoken dialogue. They could, however, perform using song and dance, comic jokes, and bits of wordplay, and from these strictures the routine-based form of Panto was born. Woods explains: it “allows for a story to be told without lots of dialogue.” However, it is far from silent.

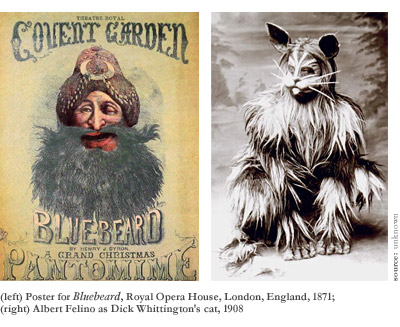

Panto is a hybrid comic form that emerged from the Commedia dell’Arte in the 16th and 17th Centuries, involving slapstick, farce, and other routine-based physical humor. As the form evolved, it grew from the inspiration of the Harlequinade in the 18th Century and the Burlesque in the 19th Century, becoming filled with spectacle—cross-dressing, clowning, song and dance, humans dressed as animals, and sexual innuendo were all part of the show. Eventually, pop culture references and social satire became part of it. In Imaginary Beasts shows, this has included everything from jokes about Beyoncé and Lady Gaga to the presidential election and healthcare reform. All of these elements are performed against a backdrop of classic stories, fairy tales, and popular legends.

Common Panto stories include Cinderella, Aladdin, Jack and the Beanstalk, and Puss in Boots, but any classic tale will do, as long as it can end happily. “At the center of the spectacle,” Woods explains, “the most important element of all—the battle of good versus evil—is played out.” No matter what story it is, good always triumphs over evil in the end. And the “key element,” Woods emphasizes, is audience participation. “Audience members don’t have to leave their seats, but they do have to boo the baddies and cheer the goodies,” he explains. The audience is always on the side of good, right, and true, and it is only with their enthusiastic support that evil is vanquished in the end.

It was in a theatre history class at Hamilton College that Matthew Woods first became interested in Pantomime. He had already developed an interest in Vaudeville and Commedia dell’Arte, and, he explains, he was “intrigued by this currently produced style of performance that uses a classic, traditional form.” In his junior year abroad in England, Woods got direct exposure to Panto in the culture where it is most often performed. In London during the holiday season, professional Pantos are produced with famous actors, but in England’s small towns, nearly every community has its own Panto. “There is a spirit of festivity and community that brings people together in wintertime,” recalls Woods, “and that really spoke to me at the time.” When he moved to Boston’s north shore eight years ago, he began working for Sleepy Lion Theatre in Topsfield. “We worked out of a barn,” he says, “and the owners of the farm were British. They asked the company to do a Panto, and I was eager to try my hand at it.”

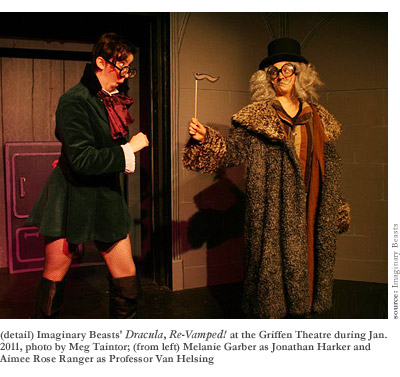

Woods and his collaborators decided on the most traditional Panto of all, Cinderella, for their inaugural effort. They were offered a performance space at the Topsfield fairgrounds, and given very little time to prepare. “We had three weeks from start to finish, including writing the script, rehearsing, and constructing costumes and sets,” he remembers with a smile, “and a cast of twenty-two actors.” They managed to pull it together, and on opening night they hosted a big dinner and reception for the community, in the true spirit of Panto. “It was a completely magical experience in the end,” says Woods, “and I’ve been doing it ever since.” He put on two more Pantos with Sleepy Lion Theatre, and then went on to found Imaginary Beasts, producing five in Topsfield, South Hamilton, and Gloucester. His most recent production, Dracula, Re-Vamped!, played this January to enthusiastic audiences at the Griffen Theatre in Salem.

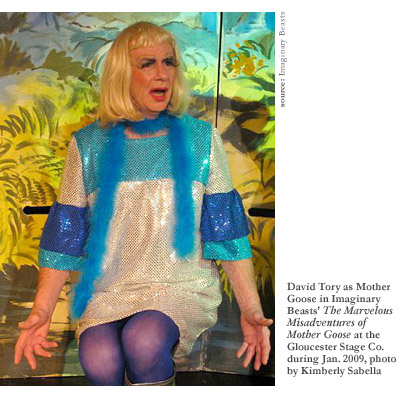

With every classic plot, the characters found in the story are assimilated with traditional Panto characters, which include the Dame, who is a woman past her prime with a particular fondness for young men; the Pantaloon, who is a miserly and foolish father figure; the Principal Boy, who is the young hero embarking on a great adventure; and the Principal Girl, whose personality changes with the times, but is always the object of the Principal Boy’s affections. While historically, the Principal Girl was a damsel in distress waiting to be rescued by a man, in Woods’ productions, she is always a strong, capable character who plays her own part in bringing about the happy ending. Typically, the existing characters in a story are adapted to fit these Panto types—Mother Goose is a kind and charismatic Dame, Doctor Seward is the dim and stingy Pantaloon in Dracula, Jack is the adventurous Principal Boy in Jack and the Beanstalk, and Cinderella is a beautiful but unlucky Principal Girl.

In addition to these key roles, a Panto is populated by a collection of other comic types that help make up the balance of good and evil. Often there is a Second Boy or Girl who acts as the audience’s friend, and a Henchman who is a bumbling sycophant coupled with the Principal Baddy. Also commonly seen is a Comic Duo made up of a straight man and a foil, much like the Vaudeville acts of Laurel and Hardy or Abbott and Costello. Every Panto has a Skin Part, which is an actor (or two) playing an animal, who nearly always falls on the side of the goodies. In Imaginary Beasts’ own tradition, the company’s productions feature a llama named Mr. T, in honor of the real llama that lived on the north shore farm where Woods held his first Panto rehearsals. And of course, in every Pantomime there appears a Benevolent Agent, often known as the Good Fairy, and her arch-nemesis the Principal Baddy, or the Demon King. Sometimes the existing characters in the story may fit into these roles. Dracula, for instance, is the Principal Baddy in his story. Otherwise, a character may be invented within the world of the story to accommodate these types. In Woods’ production of Treasure Island, the Principal Baddy was “Floody Mary, the Wicked Witch of the Wet,” while in his version of Sinbad the Sailor, Sinbad finds a broken old spigot out of which the Good “Fairy Faucet” would appear.

A key element in Pantomime is the tradition of gender-bending performances. The role of the Dame is always played by a man, and the role of Principal Boy is always played by a woman. The audience gets endless pleasure from watching a man parade around in a hoop skirt, and a young woman fall in love with the leading lady. The audience’s joy comes from seeing how unconvincing the actors are in their parts. In Mother Goose, the man playing the Dame first enters to tell the audience about “her” magical goose, making a show of speaking in a high voice, gesturing with soft hands, and crossing his legs. While playing up such “feminine” traits, he ensures that he simultaneously shows off his large feet and hairy limbs. In Dracula, the woman playing Principal Boy Jonathan Harker ties her hair back and bounds around the stage with a young hero’s reckless enthusiasm for rescuing Lucy. But she also wears a costume meant to show off her shapely feminine form, so when Harker comes face-to-face with the woman he loves, we cannot help but notice “his” feminine features and long bare legs.

These performers consciously emphasize how different their own bodies are from the roles they are playing for the sake of humorous entertainment. In Imaginary Beasts productions, the costuming, done by designer Cotton Talbot-Minkin, always adds an extra comic edge for the gender-bending performers. The Dame finds occasion for several outfit changes, like Mother Goose coming out in a glittering ’60s mini-dress after looking in the Pool of Beauty, or Sinbad’s mother Gussie dressing up in an Arabian Princess costume for her visit to the Sultan. And the Principal Boy is often called out on “his” revealing clothing choices. In the Beasts’ production of Dracula, Jonathan Harker’s outfit of tiny spandex shorts and knee-high boots led Dr. Seward to comment to Lucy that her unworthy hero was “barely wearing pants.”

Perhaps the most important element of Panto tradition is its routines. As Woods explains, “you cannot have a Pantomime without plenty of audience participation.” Routines are “the vital heart of a good Panto.” Each character typically has a personal relationship with the audience, which is established and then cultivated through moments of direct address. A Panto character will always try to enlist the audience to be on his side, usually demonstrated through moments of enthusiastic vocal support. The most basic, and also the most essential, example of such a routine is the audience cheering the goodies with shouts of approval, and discouraging the baddies with shouts of “Boo, Hiss, Boo!” At the start of the show, the Good Fairy introduces this routine, as she asks the audience to help her fight for the side of good, right, and true. From then on, the audience’s vocal support provides the necessary energy for the plot to move forward.

As the show progresses, the audience must continue to help out as the characters get lost, tangled, or trapped in plot twists. Common routines include moments of call-and-response, such as “Oh No It Isn’t / Oh Yes It Is!” and “Which Way Did He Go? / He Went That Way!” In these routines, the audience always supports the side of the goodies, agreeing with their proclamations and helping them on their quest to catch the baddies. The audience’s willing participation is always necessary to advance the plot in some way. Often there is a sing-along, which helps to encourage a goody or even to vanquish a baddy. In Imaginary Beasts’ Mother Goose, the plot was modeled after Mamma Mia! and the entire show was set to ABBA songs, which enticed giggling audiences to sing along to everything. In another traditional routine, a goody asks the audience to keep a look out for an item placed onstage, and throughout the show the audience protects the object by scaring away anyone who approaches it. In the end, the object always turns out to be highly significant, such as the Book of Wonders, which holds the final page of Sinbad’s story, or the lantern that lights the dark passageway where Dracula is found hiding. The object is thus involved in bringing the plot to a happy conclusion.

Probably the most beloved of all Panto routines is “It’s Right Behind You!” in which the audience saves a good character by warning him of an approaching baddy. The good character starts off by asking for the audience’s help, explaining that if they should see something sinister pop out upstage, to shout loudly “It’s Right Behind You!” so he will know to make his escape. Then comes the delightful routine of “practicing.” The goody asks the audience to give it a try by imagining a frightening figure right behind him, and right on cue a baddy pops out in the background. As the audience shouts out in earnest, the well-intentioned but painfully unobservant goody, believing it to be merely a practice round, makes a big show of turning around to catch the intruder. He misses seeing the baddy, who disappears again just in time. The goody then faces forward to congratulate the audience on a respectable first try, and asks the boys and girls to see if they can’t be a bit louder for a second round of practice. This game is repeated until the goody finally realizes the audience is shouting out a true warning, and turns around to come face-to-face with the grinning baddy. Children in the audience of many an Imaginary Beasts performance are so delighted by the routine that they take to shouting out “It’s Behind You!” throughout the rest of the show, each time a baddy enters upstage.

Whether it be to advance the plot or simply to put on a show, every routine is crafted for the audience’s delight. Tried and true routines often appear purely for entertainment, such as a “slop scene,” in which a buildup occurs to a character inevitably getting a pie in the face. There is also the joy of the “rope trick,” in which a rope is stretched taut across the stage, a group of characters exit pulling it offstage left, and a few moments later enter pulling the still taut rope onstage right. A good Panto is never without moments of witty wordplay, in which the audience happily groans to a series of terribly bad puns. In Imaginary Beasts’ production of Sinbad the Sailor, the baddy was a Gorgan named Zola (or, the Gorgon Zola) whose presence always elicited strings of “cheesy puns” from the other characters onstage: “That lousy limburglar! I knew she was up to no gouda!” In every successful performance, the audience’s enthusiastic voice becomes like another character in the play. And each performance is unique. It is up to the actors to improvise enough to include the particular contributions of each audience, but the performers must also have command enough to lead the audience back if they begin to distract from the story. “A good Panto actor must develop a sense of knowing when to stray and when to return to the plot,” says Woods. “As a general rule of thumb: always know the thrust of your scene.”

Woods relishes the “collaborative nature” of theatre, and he says he “tends to indulge in it” when creating a Panto script. Though his approach isn’t typical, it does embody the community spirit of the form—everyone involved has a voice. “Essentially,” he explains, “because Pantos are based on fairy tales and well-known stories, the key story and plot elements are already in place.” The writer’s task then, is to develop a scenario, or a description of what should happen in any given scene. “The description includes plot information that must be conveyed, any traditional routine that needs to be included, sources for inspiration, and small scraps of dialogue or a joke.” The actors take the information from the scenario and improvise a scripted scene. Each scene gets continually refined during the rehearsal process, and eventually Woods takes all of the material that has been generated and sits down to write a final version of the script. Still, with so much room to play, it is never quite finished until right before the show opens. Moreover, even with final scripts in hand, there is room for the actors to improvise during performance. And they must, for with the unpredictable element of audience participation, the show is never the same twice. Each night laughs come in different places, new jokes are added to reflect the current news, and particularly talkative audience participants become integrated into the show.

Ultimately, for Matthew Woods, putting on a Panto is always a magical experience. “Remember what it felt like to be a child who could believe in possibilities and make-believe?” he asks. Panto captures that wonder and festive spirit. But it is not simply a nostalgic entertainment. “Panto has always been a theatrical form that brings us face-to-face with our greed, our prejudices, our cowardice, and our dishonesty, but it does so in a way that forces us to laugh at ourselves. In the end, virtue is rewarded, true love conquers evil, and everyone lives happily ever after.” As for Imaginary Beasts? They continue to play, and happily look forward to their next adventure.