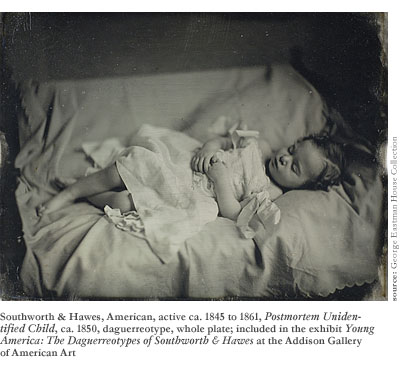

The first thing I noticed about New England upon my recent relocation from San Diego was the pervasive sense of history here. Of course, that’s not to imply that Southern California has no history, but unless one is determined to look beyond the shiny, new strip malls, it’s relatively rare to run into much recognition of that fact. In contrast, New England explodes with artifacts reaching back to its colonial past, and history can be encountered almost everywhere one turns. Young America: The Daguerreotypes of Southworth & Hawes, on view at the Addison Gallery of American Art through April 9th, brings a piece of this ever-present past to Massachusetts after first being exhibited in New York City and Rochester.

Although a collaboration between two New York photography institutions—the George Eastman House and the International Center of Photography (ICP)—this impressive exhibition featuring over 150 daguerreotypes is firmly rooted in New England’s history. Both photographers, Albert Sands Southworth (1811-94) and Josiah Johnson Hawes (1808-1901), were raised in New England (Southworth even attended Phillips Academy), and they established their working partnership and daguerreotype studio in Boston in 1843.

I first saw the exhibition at its opening venue in New York City—a setting that struck me as potentially out of step with the antiquated scenes of Boston and quiet, romantic portraits of the city’s mid-19th Century denizens. However, I was pleasantly surprised that even after a chaotic, solo trek to the ICP through rainy downtown Manhattan and multiple subway transfers, Young America succeeded in transporting me to a quieter time and place. Part of the success may be attributed to the fact that the exhibition was located on the basement floor of the ICP, whose low lighting and location set it apart from the rest of the museum and allowed for a more focused and contemplative viewing. Seeing the exhibition again in Andover recently brought me back to that strange, otherworldly sensation. It happened to be another overcast and rainy day, and although this time located on the top floor, the exhibit was once again set apart from the other galleries by darkly painted walls and low lighting—so low, in fact, that it was difficult to read the descriptive plaques. In some cases, the plaques seemed to be intentionally hidden in the shadows beneath the daguerreotypes. The images themselves were all set inside new reddish-brown or gold frames and casings, fashioned as they would have originally been seen.

Although the images that make up Young America now appear as relics from an antiquated past, at the time when Southworth and Hawes established their studio, daguerreotypes were among the most modern technology available on the market. They set up shop just four years after Louis Jacques Mandé Daguerre publicly announced his discovery in Paris in 1839. By 1853, there were reportedly 2000 daguerreotypists practicing in America at the time, and most were in the business purely as a way to make money. Rather than being content with a mechanical, working knowledge of the medium, Southworth and Hawes sought to elevate their photographs to the realm of fine art, which accounts for the images’ compositional beauty.

Soon after their introduction, daguerreotypes quickly became a popular form of portraiture. At this time portrait paintings were far and away the most patronized art form in America, and American sitters preferred portraits that achieved a truthful likeness, as opposed to a more idealized vision of themselves. Daguerreotypes became synonymous with truthfulness, and there was a belief that the camera revealed the inner conditions of the soul that a painting could never achieve. One of the characters in Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The House of Seven Gables illustrates this belief by stating that the daguerreotype “brings out the secret character with a truth that no painter would venture upon, even could he detect it.” Southworth and Hawes, dedicated as they were to making fine art, sought to do just this.

Their portraits range from famous political and cultural leaders of Boston to ordinary citizens, but all have an equal intensity about them. The exhibition begins with images of some of 19th Century Boston’s most illustrious figures, many of which later were translated into woodcuts, lithographs, or engravings, for the public to see the likenesses of individuals they knew only through the news. Although they are public portraits meant for public consumption (and therefore consciously more firm, stern, and sober than private portraits), these do achieve a sense of each individual’s personality. Southworth and Hawes capture the image of the poet Grace Greenwood, for example, with enormous, wild eyes that are strikingly frightened-looking. Reverend Rollin Heber Neale, on the other hand, may have a wild look about him from his unruly hair, but his stance and powerful stare command attention and respect.

The public portraits lead into the next section, private portraits, meant for viewing by family and friends. Despite the fact that Southworth and Hawes approached private portraiture differently than that meant to be seen in a public context (they explain that “a likeness for an intimate acquaintance of one’s own family should be marked by that amiability and cheerfulness, so appropriate to the social circle and the home-fireside”), aesthetically, they do not offer immediate difference from the public portraiture. Many sitters look away from the camera and several are unsmiling. However, some of the most striking and illuminating images in the exhibition are showcased in this section—those depicting the two artists with their families. The two families of Southworth and Hawes were close-knit (made closer when Hawes married Southworth’s sister, Nancy Stiles Southworth), and this intimacy is revealed through the natural joy that is depicted in the images. They, like their sitters, may also have been interested in locating and preserving their likeness, but they were also able to loosen up more and experiment with the camera. Because of this, these images come closer to revealing the individual’s personality than any of the others.

On the whole, Young America achieves a reflective look back at a time of great change in America—change that may have evoked both excitement and uncertainty in its citizens. Americans were actively discovering new technology, new lands, and working to solidify a visual identity for themselves. Southworth and Hawes participated in this quest by assisting with their sitters’ earnest desire to present a lasting and truthful image to the world. As a result of their success, I left this exhibition feeling oddly nostalgic for anonymous people who lived in a time long past. These daguerreotypes may belong to Boston, but the sitters’ desire to carve a lasting place for themselves in an unstable world has the ability to resonate with everyone. Even Southern Californians on a sunny summer day.