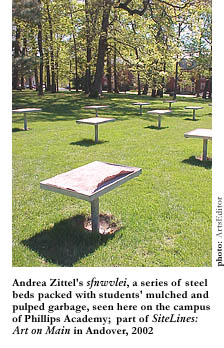

I was standing among the 24 nearly identical sfnwvleis that Andrea Zittel and her horde of helpers from Andover Youth Services had arranged in perfect rows when a peppy 40ish woman of East Asian descent bounded over from the nearby tennis courts and asked, “Excuse me—but do you know what this is?” It would have been the truth, but it wouldn’t have been very polite of me to say to a trusting stranger, “Oh, these are sfnwvleis, of course!” Not even sure how I might have pronounced that word anyway, I said instead, “That’s just what I was wondering! But do you know about the SiteLines art project that starts in Andover today? Well, this is a conceptual art piece that’s part of it. The artist made the piece with the help of some students.”

Abandoning the puzzled look she’d been wearing on her face, the inquisitive stranger stifled a chortle and admitted that she and her daughter—whom I’d noticed blowing overhand serves past her father moments before—had come to the tentative conclusion that those tray-like things on stands over there in the grass were barbecue grills. An odd place for them, perhaps, with no picnic tables nearby, but what else could they be? I concurred that they might well have puzzled me, too, had I not just spent 15 minutes tracking them down with my SiteLines map.

Abandoning the puzzled look she’d been wearing on her face, the inquisitive stranger stifled a chortle and admitted that she and her daughter—whom I’d noticed blowing overhand serves past her father moments before—had come to the tentative conclusion that those tray-like things on stands over there in the grass were barbecue grills. An odd place for them, perhaps, with no picnic tables nearby, but what else could they be? I concurred that they might well have puzzled me, too, had I not just spent 15 minutes tracking them down with my SiteLines map.

Many more maps just like mine—bright yellow-and-black affairs with one panel devoted to each of the nine participating professional artists—have been printed for distribution to visitors to SiteLines: Art on Main. Most of the site-specific pieces, collaborative efforts of the guest artists and their young apprentices that “connect the academy with the wider community” in an exploration of the Andover area’s history, geography, and culture, are easier to find than Zittel’s. And since the temporary outdoor art project, presented by Phillips Academy and its fabulous Addison Gallery of American Art, will be up until September 29, there’s plenty of time to find them all.

Arranged on a slope of manicured greensward on the campus of Phillips Academy, Zittel’s sfnwvlei—standing for something for nothing with very little effort involved—hides among a grove of shade trees banking the Vista fairway, just out of sight of the pristine and chilling view of the grand Addison Gallery across the street. Zittel, contributing to the delinquency of minors, probably encouraged her student helpers to rib the regimented sterility of this preppy landscape, noting that environmental art should feel free to blend as well as bicker with its surroundings. The steel tray of each conceptual barbecue grill is filled with a textured, reddish-brown cake of dried paper pulp. Individually and collectively the grills are curious to behold, but their blunt yet oblique symbolism seems a bit too cerebral to be shocking, a little too cool to be very engaging. Nevertheless, it’s encouraging that a visiting artist would have the gall to nurture rebellion in young artists, as long as it’s summoned instead of imposed.

Given the opportunity, I would have taken that trusting soul on the complete SiteLines tour when done playing tennis. Promising to return her to her daughter and husband in a couple of hours, I would have walked her past the Pathways project on the weed-free fairway—directed by Jessica Stockholder, who had enlisted the help of some Lawrence High School students. I would have walked her down the street, where we might have wandered past the first of several copses that multimedia artist Arthur Ganson and his apprentices from Greater Lawrence Technical School had wrapped with ribbons, each bearing a proverb of a single student’s composition—some of them witty (“It’s not where U from, it’s where U at!”) and some sentimental (“Smile because you never know who’s going to be falling in love with it.”).

Before taking my companion to watch the wizardly Ganson stamp fresh proverbs onto new ribbon with a nutty-looking printer called a Thought-o-Graph, which he assembled from spare parts with the assistance of his student staff, I would have led her into the Andover Historical Society to see the glass cases of miniature antiques that archeological artist Mark Dion had chosen from the Society’s collection—four or five cases full of loosely categorized objects: brooms, coal shovels, and buckets; rolling pins, grinders, and sewing machines; barrels, wheelbarrows, and rakes.

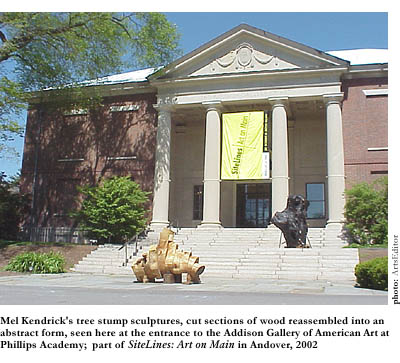

Later, passing Mel Kendrick’s tree stump sculptures on the steps of the Addison—ungainly libidinal things in such a sanitary setting—that had been sliced up and pieced back together at a Haverhill sawmill with Phillips students, I could have walked her into the Gallery’s first-floor hallway to see Dion’s large-scale photographs of selected miniatures. She would have loved those—and we could have gotten a glimpse of the impressive solo work of all nine participating artists, too, on view until July 31 in the complementary indoor exhibit InSite: Nine Contemporary Artists.

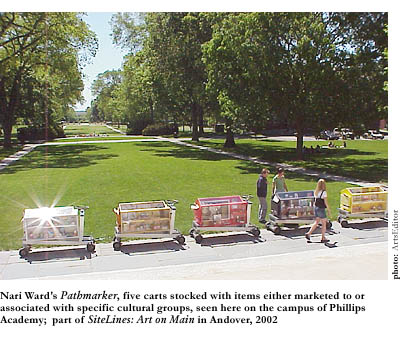

Maybe the five art carts Nari Ward designed with his crew of public and prep school students from Lawrence and Andover would roll by, their bifurcated transparent sides offering views of everyday objects in orderly assortment, the way they would in the Jamaican neighborhoods that inspired them—cereal boxes, canned soups, and mayonnaise jars—in thanks to the higher powers that made that prosperity possible. And my companion would not have wanted to miss Ward’s wild shopping cart in the Addison—the tall and statuesque skeleton of black and red tape rising geometrically from the depths of the ordinary street person’s cart like an atavistic idol, symbolizing credits and debits on the one hand, blood and the abyss on the other—and supplemented by nearby video footage of the deadpan artist wheeling his totemic cart down a wide boulevard in his hometown Harlem neighborhood. “Wow!” I can hear her saying. “Isn’t that bizarre!”

I did not invite her along, of course. By the time she approached me at the sfnwvleis, I was nearly done with the SiteLines: Art on Main tour, ready to ride my bicycle through the backwoods housing developments, past McMansions and renovated farmhouses, to catch the train back to Boston from Lowell. Unfortunately, I wasn’t going to be able to stick around until evening to catch Mosquito Cinema, a video presentation about movie-watching that is “based,” says the map’s caption, “on a series of interactions between the artist [Lee Mingwei], student participants, and spectators.” But I’d been in Andover since early afternoon, and a new segment of the Mingwei-motivated project will be showing each Saturday at 9 p.m. through September anyway.

The opening festivities had started with African drummer Wole Alade leading a troupe of student beat-keepers and dancers on a 20-minute burst of rhythmic rapture. I’d seen Adam Weinberg, director of the Addison Gallery of American Art, introduce some of the organizers of this town-gown collaboration, including Lawrence High School art teacher David Meehan (pony tail, warm style, and black leather jacket) and an unassuming man in men’s shop attire who might well have been Andover’s mayor. They had thanked just about everyone in Middlesex County for helping with the project—everyone from the staff of the Essex Art Center and Andover’s Memorial Hall Library to the hundreds of students from Doherty Middle School in Andover, Andover High School, and Greater Lawrence Technical School.

The opening festivities had started with African drummer Wole Alade leading a troupe of student beat-keepers and dancers on a 20-minute burst of rhythmic rapture. I’d seen Adam Weinberg, director of the Addison Gallery of American Art, introduce some of the organizers of this town-gown collaboration, including Lawrence High School art teacher David Meehan (pony tail, warm style, and black leather jacket) and an unassuming man in men’s shop attire who might well have been Andover’s mayor. They had thanked just about everyone in Middlesex County for helping with the project—everyone from the staff of the Essex Art Center and Andover’s Memorial Hall Library to the hundreds of students from Doherty Middle School in Andover, Andover High School, and Greater Lawrence Technical School.

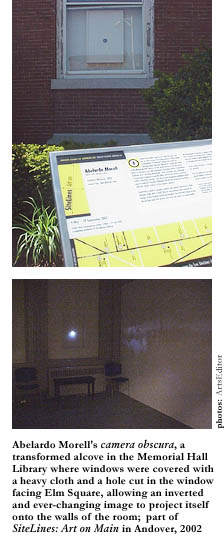

Then I’d heard Soul Kaliber, an a cappella “spoken-word” group, get completely down with poems for several voices about “truth, knowledge, power.” From there I’d joined the crowd behind bagpiper John Simeone up Main Street to the public library, first for a show of hip-hop dancing by 10 or 12 mocha-skinned young girls from Lawrence Ballet Academy—in blue jeans, spangled bandannas, and powder-blue t-shirts—looking a little too adorable to be believed; then inside the library for a look at photographer Abelardo Morell’s camera obscura demonstration, in a room that he told us is “the equivalent of being inside a camera,” with an inverted view of the scene outside projected from a pinhole in the outside wall onto the entire surface of the opposite wall.

A lot of the collaborative environmental artwork in SiteLines does warm the chilly atmosphere of Andover’s Main Street a little, especially when considered in light of the fact that several hundred students got to participate in the project. Downtown in front of the Old Town Hall, for example, there’s the quirky little observation deck that Jason Middlebrook erected with the help of Andover students and residents, whom he surveyed for ideas. From its railing you can overlook the busy sidewalk and street and read the illustrated plaques, like those found on similar decks in bog-side or ridge-top nature preserves. Can you identify the names and habits of various species found in this native habitat? Each seems tamer than the next. Squirrels with their nuts. Pigeons with their breadcrumbs. Homo sapiens with their CD collections and their SUVs.