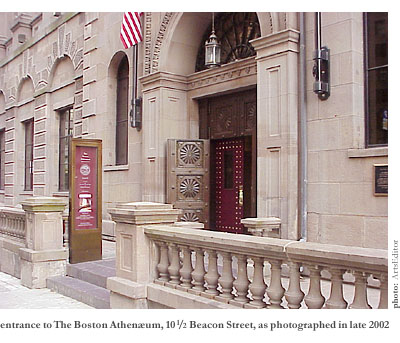

With its imposing, Italianate façade, its intimidatingly Grecian name, and its quaintly Harry-Potteresque address (10 1/2 Beacon Street), the Boston Athenæum is the kind of place in which you instantly feel underdressed if you are not wearing your Sunday best. Arriving there fifteen minutes late and without so much as an old school tie to distinguish my limp and grimy collar, I felt rather like I did when I first arrived, quite unprepared for the culture shock, at the porter’s lodge of my college in Oxford, England. As bow-tied associate director John H. Lannon fussed about the time, insisted on our checking our bags, and flatly refused to consider letting us wander around a little on our own after the guided tour was over, I felt the same mixture of disappointment, irritation, and contempt as that which had darkened my brow when I was first told that Oxford lawns are only for looking at. I thought I had escaped such stuffy, uptight nonsense when I set sail for the free and easy New World. Such paranoia about the honesty of an (ahem) upstanding member of the independent arts press hardly boded well for what we might encounter beyond the white marble vestibule.

But you could have told me to expect such treatment, couldn’t you? You’ve heard of the Athenæum, haven’t you? It’s that posh, members-only library down the road from the State House; just another old-moneyed Beacon Hill institution far removed from the daily reality of people who actually have to work hard for a living. Right?

Well, the bit about the old money is certainly accurate. Modelled on the Lyceum and Athenæum in Liverpool, England, the Boston Athenæum was founded in 1807 by the members of a local literary club. Financed by the ample proceeds of the china trade and frequented by the likes of Emerson, Longfellow, Webster, and Amy Lowell, the Athenæum soon became Boston’s cultural powerhouse.

Most of its collection of paintings has long since been donated to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (founded in 1875), and nor can it still claim, as it did in 1851, to be one of the five largest libraries in the U.S. Nevertheless, its 750,000-strong book collection remains highly impressive—albeit that it is largely confined to history, literature, and fine arts. Of particular note are the various unique and priceless “special collections,” which include the personal libraries of Henry Knox and George Washington, as well as the “King’s Chapel Collection,” a collection donated to the Massachusetts Bay Colony by the “infamous” (as our evidently Jacobite guide called him) King William III.

The issue of what to do with all these books has been a thorn in the side of successive directors. The problem was not even solved when the Boston Athenæum moved, in 1849, to its current, purpose-built premises, having outgrown a number of previous addresses. Architect Edward Clarke Cabot’s acclaimed original three-story design was augmented in 1913-14 to the tune of two extra floors, but even the more recent letting of the basement of an adjoining building promises to be no more than a temporary solution, given the Athenæum’s continuing acquisition of more than 5,000 new books a year.

But the more pressing problem in latter years has been how to preserve what the Athenæum already possesses. The ingeniously contrived “Mediterranean climate” boasted of when Cabot’s building first opened may have been bliss for readers, but it was not conducive to the health of the books, such that their condition, by the end of the last millennium, was becoming sadly dilapidated.

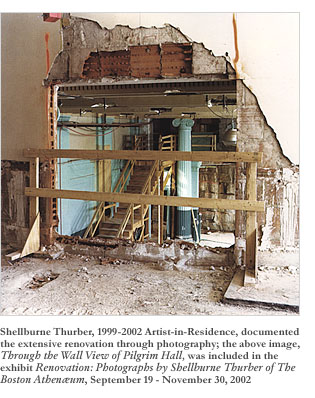

Hence, the trustees decided that bold remedies were in order. Armed with almost thirty million dollars from a highly successful fundraising drive, they closed down 10 1/2 Beacon Street for three whole years in 1999 and practically demolished the entire interior so as to accommodate both a greatly expanded conservation department and a highly elaborate system of air-conditioners, heaters, and sprinklers, bringing the building’s safety and climate control system up to the high modern standard for libraries containing unique collections.

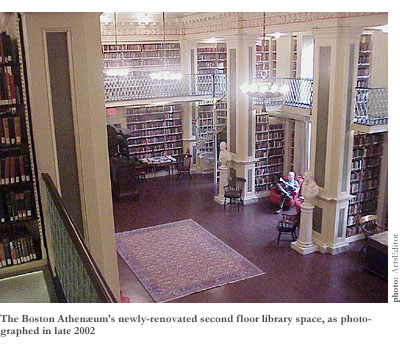

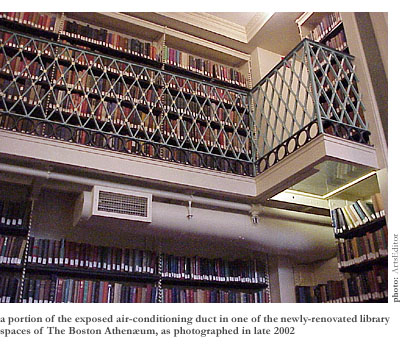

That three-year project has just ended and Lannon takes us from floor to floor, describing in intricate detail all the alterations the building underwent. He dwells with obvious relish on all the design problems that had to be overcome—all the false walls and ceilings that were installed to disguise the miles of ductwork, the 130 tonnes of machinery on the roof that makes it all work. He even offered to show us the electrical cupboards.

But one can forgive him his inordinate enthusiasm. After all, he has worked at the Boston Athenæum for twenty-five years. He is the one person in the world (besides us) who knows that there are 162 steps from the first to the fifth floor. He was one of the few staff members to remain on site throughout the demolition, and there was a photograph in the exhibit Renovation: Photographs by Shellburne Thurber (open to the public) of the demolished gallery against whose stained white walls he played racquets one unforgettable morning.

Alas, there is no picture of the game in progress, nor any record of the score. But, then again, it would all be more Greek to you anyway, wouldn’t it? I mean, be honest, you’ve never even heard of racquets, have you (as opposed to racquetball, from which Lannon insists it is entirely distinct)? And doesn’t that just confirm your prejudices regarding the denizens of the Boston Athenæum? God knows that the people who used the “real tennis” court in Oxford are hardly the kind of people with whom you’d want to share a game of squash.

Lannon, too, is well aware of this popular perception. Visibly bristling, he denies categorically that the Athenæum is a “Brahmin” institution only open to the right sort of fellow. “We are independent, not elite,” he insists, drawing our attention to the portrait, displayed prominently in the meeting room, of the first woman to be admitted as a member. He also points out that the Athenæum has a membership of over five thousand people, making it the largest and most successful membership library in the U.S.—a status that hardly coheres with the stereotypical assumption of its domination by a small coterie of Beacon Hillbillies. And, most crucially, he denies being able to recall a single membership application ever having been turned down.

Of course, if we were unkind we might suggest that that is only because the application form, which demands an annual fee of up to $150 together with three letters of reference, is sufficiently off-putting to discourage all but the right sort from applying in the first place. On the other hand, it is only fair to note the half-price fee for the under-forties, introduced to encourage younger members to join. Moreover, the Boston Athenæum’s latest brochure insists that one of its chief post-renovation goals is to reach out to the local community to seek to attract a wider diversity of members.

Only a churl would doubt the sincerity of that aim, yet it is clear that the Athenæum will have to do a lot more than offer a discretionary membership to every local high school principal if it is to fulfil that aim. It needs to make clear why kids should want to get their Harry Potter books from its newly-expanded children’s department in the first place. Highlighting 10 1/2 Beacon Street’s inevitable ghost might be a good start in that regard. However, the librarians also need to spell out why the little wizards should feel the need to start writing checks once they stop believing in the supernatural. Why isn’t it enough to become a member of the Boston Public Library?

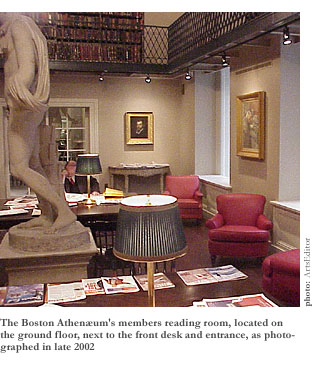

Lannon’s rather lame suggestion is that “you might not have to wait as long to get your hands on a new, popular book at the Athenæum.” However, it seems to me it is the building itself that is the institution’s chief lure. As intimately charming as any Oxford college library, it boasts five double floors, all beautifully decorated in the neo-classical style and commanding fine views of the adjacent Granary cemetery. It strikes me as the perfect place to write a Ph.D. thesis, and it is mystifying that the institution’s membership does not contain a higher proportion of students, especially now that the Boston Athenæum has a Web presence.

Then again, if catering to students and scholars was the Athenæum’s raison d’être then surely it would simply allow itself to be absorbed by Harvard or Boston University. Such a move would also make sense in the context of its evident desire to take research ever more seriously (witness all the book-preservation measures). Presumably its reasons for not going down the academic road include preserving access for people not affiliated with academic institutions. But the problem is that most of these people are simply not at liberty to spend all day studying in a library, however beautiful. What, then, can the Athenæum offer them that the Boston Public Library can’t?

The brochure suggests “perusing the latest issue of a favorite periodical” during one’s lunch hour. And, to be sure, the fifth floor members’ lounge, with its sunny, panoramic terrace, is as fine a setting for a sandwich as Boston has to offer. But surely this is not enough. No, I suspect that it is the Athenæum’s ability to expand and improve its events calendar that is the key to attracting a wider membership. Weekly literary, historical, and culinary discussion groups are unlikely to tempt the NPR-donating thousands in the Boston area, but a regular program of compelling and challenging speakers, debates, and films just might. (That is, for example, how the Oxford Union persuades students to part with $150 of their parents’ money).

In other words, the Boston Athenæum needs to strive to reclaim its illustrious history as a beacon of topical debate and cultural innovation. As things stand, it seems—consciously or otherwise—to wallow in its sheer historicalness. Different current members describe it as “an island of civility in an increasingly less civilized urban world,” “an institution where history is alive,” and, most tellingly, a place “which exists for those who love it as much as a state of mind as a physical place.” Such comments give the impression of an institution still languishing in the days of gentleman-amateurism, yet to adjust to the professionalization of—and mass participation in—contemporary arts, culture, and learning.

Or take the building itself. Lannon almost winced as he pointed out the one large air-conditioning duct that had proved impossible to conceal. Yet, rather than spending millions on such sleights of architectural hand, mightn’t the designers of the refurbishment have been instructed, instead, to make a bold feature of the ducts, openly exposing them to view like a nest of silver snakes? Wouldn’t that have constituted a far more powerful statement of 21st Century intent than any number of press releases mentioning the phrase “community outreach”?

On the other hand, maybe it would have been nothing but gross aesthetic and historical vandalism. All I know for sure is that, notwithstanding the beauty of its premises, the value of its collections, and the worthiness of its intentions, the Boston Athenæum has a long way to go to fulfil director Richard Wendorf’s desire to make it “a welcoming institution” to potential new members. Then again, maybe that’s just bitterness over the fact that I didn’t manage to stuff any of George Washington’s books into my coat when Lannon’s back was turned.