Maybe it has something to do with being from the Isle of Man, an ancient place both of and separate from united empires. Something about those with Manx ancestry, that they possess an ability to light others from within, that they give something innate to others, allowing them to shine in exactly the way they were meant to. Paul McCartney descends from Manx lineage; my supernaturally soulful cat, Frankie, is a Manx. And Chris Killip is, too.

Killip’s newly printed photobook, The Station, illuminates the Thatcher-era, anarcho-punk boys and girls and their Gateshead Music Collective in Newcastle, north east of England, and the sway that their music and self-operated club held over their existence at the time. The Station’s story starts in 1981, but Killip’s began in 1964 with a jump from the Isle’s capital of Douglas to London and into an eventual photographer’s assistant role—a serendipitous detour away from an intended career in hotel management. Killip’s later stint as founder, curator, and director of the Side Gallery in Newcastle bore his seminal photographic work to that point, his Henri Cartier-Bresson Award-winning collection of 4 x 5 film slides depicting Britain’s underclass of the 80s, In Flagrante (1988).

Killip’s 1985 Station collection, originally seen as his tabloid-sized series with Pony Ltd. two years ago, gets an immaculate, printed edition here from publisher Steidl in Germany; it’s a textural mic-drop for the nothing-can-replace-a-physical-copy side of the digital age debate. The photo pages inside alternate between granular and glossy, bound and oversized in a gritty cloth cover fashioned, I imagine, to endure the Isle’s relentless sea vapors. The stark black end paper lists the bands that played the club, from Blood Robots to Napalm Death, Legion of Parasites to The Reptiles.

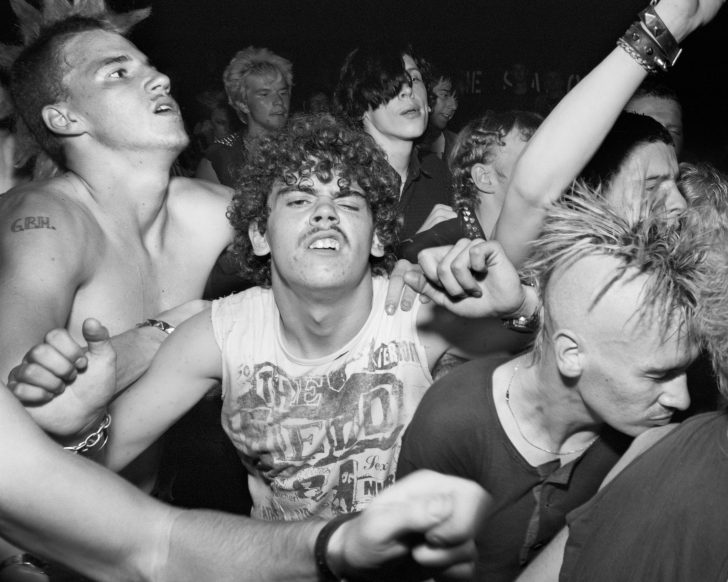

The Station’s photographs are about space, between and throughout. But the images don’t focus on the actual space of the venue itself, an old Police Social Club on Swiburne Street in Gateshead that was formed, Killip writes in his introduction, after “the collective successfully applied to The Prince’s Trust for funding to buy equipment and to refurbish the space.” While it may be that contemporary life is ineffably unmoored from the very idea of closeness (intimacy with relative strangers at a club feels like, at this moment, a future relic of our world), the soul of the collection emanates from just that—the energy of the subjects’ closeness. The proximity of the revelers (most of whom were “members of [other] local bands, who weren’t playing that evening…in the audience dancing.”) is where The Station draws its energy, its light.

Killip’s laying bare of the personalities at the club, in atmospheric black and white, evokes the way Dorothea Lange or Diane Arbus could capture the spirit, almost mystical, of working-class folks. But whereas those artists’ works often contrasted the close-up expressiveness etched onto well-traveled faces by alternately placing their subjects against wide-open vistas and the rawness of their environments, Killip stays intimate here. Although influenced by a great many photographers, he promises, “The Station was a very difficult place to photograph. The walls, ceiling, and floor were painted black, the only light came from the stage which meant that I had to use a flash. My technique came out of necessity.”

The Gateshead club, too, was a social, emotional necessity for the young musicians and fans who had migrated over from a short-lived punk venue, The Garage, in Bells Court, after its closure sometime in 1980. On top of that, a miner’s strike that wrought widespread unemployment during the same period could’ve spelled the undoing of the community. What about, then, the accompanying legacy—warranted or not—of punk music rising from a cauldron of political unrest, anger, and aggression? “The overall mood [at the Station] was a sort of joy, as the place was a celebration of punk at that time,” recalls Killip to ArtsEditor. “The place was a co-operative run by the bands and members of the audience, making it completely unlike any other venue that I knew. It was their place and their music. It was not a violent place—it was self-governing, no security, no bouncers.”

Killip also marvels that someone so obviously not “of” the punk culture of the era could have been so casually, almost indifferently, accepted at the Station during what surely must’ve been a time of wary suspicion of outsiders. “Nobody ever asked me where I was from or even who I was. A thirty-nine-year-old with cropped white hair who always wore a suit. With a big flatbed plate camera around my neck and a hefty Norman flash, with its outsized battery around my waist, I must have looked like something out of a 1950s B-movie.”

The photographs themselves unveil a propulsion, a movement from masses of youth who aren’t diametrically or socially opposed to each other’s trajectory, but instead leading each other to inclusivity, to a shared experience. In many of them, revelers get physical with each other, but not the blind pushing or deflection frequently found in punk pits; in fact, there’s guiding, excited pulling, friend’s hand in arm as they bounce inside an enervated sub-group or escort each other toward the stage.

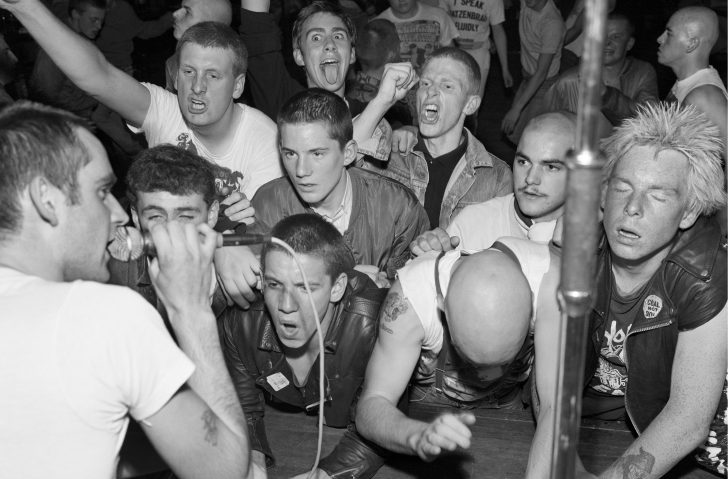

In one photograph, a throng of young men fixate their gazes at the howling lead singer onstage, a shot framed from just behind the singer’s shoulder as he grips the mic. The visages convey a kaleidoscope of feeling, from solidarity and sympatico—a commingling with each other and the lyrics—to an unbridled silliness (one self-aware punk points his tongue at Killip’s lens). There’s also rapture and dissent and melancholy all at once: a clubgoer in a vest with a frayed sticker in support of local coal mining also has his eyes closed, nearly in repose.

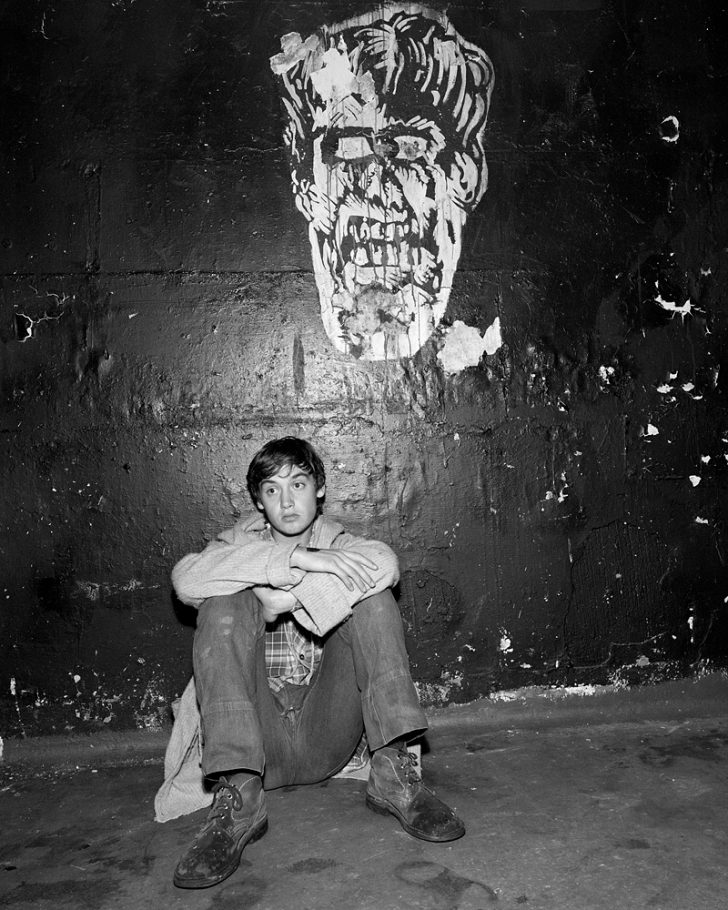

In another (and maybe The Station’s best photograph), a young man—he might as well be Quadrophenia’s Jimmy Cooper, long coat, wispy bangs and all—sits against a chipped concrete wall, knees to chest under a peeling graphic of a Frankenstein monster-ish mugshot. It’s the young man’s face that wields the picture’s power: not angry, not disaffected, but with the weight of everything that comes with wondering what’s next.

What was next for the kids of The Station? Killip crossed paths with them only once again. “In 2018, I took part in an exhibition at The Baltic in Gateshead, a venue that’s only 500 yards from where the Station was. Lots of the lads from the Station came to the show. You could see them really enjoying seeing themselves from thirty years ago.”

Chris Killip found the light within the kids of the Gateshead Music Collective, and recorded it for us to see. The pictures, though, manifest what had simply been there at the club all along. “Because it belonged to the people who went there,” Killip intones, “it positively confirmed their identity and self-worth.”

Spoken like a truly—supernaturally—soulful cat.