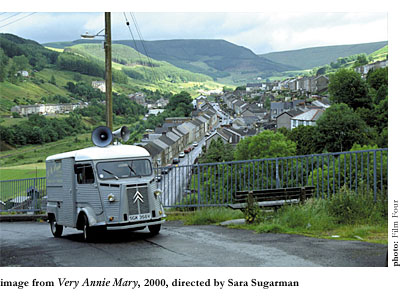

The Welsh have long been admired for their singing—for their vocal dexterity and charismatic delivery. Think the inimitable pop power of Tom Jones and Shirley Bassey, the angelic persuasion of soprano wunderkind Charlotte Church, or the force of baritone rock iconoclast John Cale. The Welsh are so infatuated with these homegrown talents that they treat their singers with the utmost respect, be they members of one of the nation’s many esteemed choral groups or among the wealth of venerated soloists. Jack Pugh is one of those talents, whose vocal renown in a small valley town in the Welsh film Very Annie Mary is so great that he is as beloved for his gift of song as he is for the valuable service he provides as the village baker (his bread delivery van is fitted with a microphone and loudspeaker so Pugh can sing arias a la Pavarotti while driving through the lush, scenic hillside surrounding the valley).

Very Annie Mary was filmed in the Garw Valley town of Pontycymmer in South Wales, and the many locals who stood in as extras provide a more authentic feel. Jack Pugh (played by Jonathan Pryce) is known to the villagers as the “Voice of the Valley,” and his twentysomething daughter Annie Mary (played by Rachel Griffiths) seeks, in the shadow of that valley and in the shadow of her father, to find her own voice by rediscovering the vocal talent she possessed before the repression of her father’s strictures and the demise of her nurturing mother. Annie’s bedridden 16 year-old best friend Bethan Bevan has a video recording of a concert recital Annie gave as a teen, but Bethan’s “sound system” is in symbolic disrepair (like her ailing immune system), and that once captured voice cannot be heard in playback.

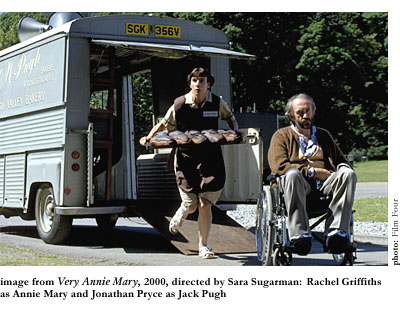

While pleasant on the exterior, thanks to his glorified celebrity, Jack Pugh treats his daughter Annie with little regard for her happiness. She lives with him, above the bakery, because she is considered “slow” and therefore unfit for marriage. An iconic free spirit, Annie’s clumsiness lends to a great deal of the film’s slapstick humor, and her simple aspirations and dreams are, to her father, less idealistic than simply childish. Therefore he keeps Annie in a sort of slavery; he prevents her from taking part in the rituals of breadbaking or singing, and she is relegated to the more menial tasks of shopkeeping and instrumental accompaniment—she is his “second fiddle.”

This dysfunctional family arrangement changes abruptly when Pugh suffers a stroke (mid-concert). His bread literally gives a life to the villagers, and when the supply is cut off, a hunger brews in his neighbors, who in addition to physical satiation long for that beautiful voice which has now fallen silent. Suddenly Annie’s responsibilities expand tenfold, to include carrying her father up and down stairs, and taking over the bakery, in which she fails miserably despite her great efforts and singularly creative approach. Ultimately, after various mishaps, Annie achieves her independence in a way that bridges a coming of age with personal rediscovery, whereby she finds her voice—figuratively and literally.

The film has an almost farcical fairy tale quality, and deftly updates many fairy tale clichés, including the happily-ever-after ending. Annie is a familiar character to us, as the child who is not allowed to grow up, and the princess waiting patiently for her prince to take her away to the castle (a house she passes every day that is up for sale and she dreams of being able to afford). Her head is not in the clouds, however; she has the will and drive to make her fantasy come to life, if only those around her would accept her for who she is! Like any fable, there is also a timeless quality to Annie’s Peter Pan-meets-Cinderella story (which is aided by the small-town setting), and that gives it a more universal appeal.

Very Annie Mary is an intelligent comedy with lots of silliness. A clueless old vicar is the brunt of many jokes, and some of the best gags make light of the church, albeit in a sporting rather than critical fashion. Pugh’s declaration that he’d like to familiarize himself with the book of Leviticus, to the point where he knows it forward and backward, prompts the vicar to warn that reciting biblical passages backwards is “the devil’s work,” and there’s an odd scene involving scratch-and-sniff bibles. There’s plenty of clever wordplay, but also a good bit of physical humor, particularly after Pugh’s stroke, when actor Pryce must rely chiefly on facial expressions to exhibit his character’s chagrin at Annie’s many blunders.

Australian actress Rachel Griffiths fits well in the title role, a lovable and sympathetic character whose bumbling yet undaunted spirit and charm maintains a light and playful tone in a potentially dark film about death and atonement. The beautiful and bouncy Griffiths has the distinction of having appeared in both Muriel’s Wedding and My Best Friend’s Wedding, but far from being typecast in marital-themed films, she continues to take on a variety of offbeat roles. Following the filming of Very Annie Mary, Griffiths came to Hollywood to appear in Blow as the mother of Johnny Depp (an actor three years her senior), and then joined the cast of the HBO series Six Feet Under.

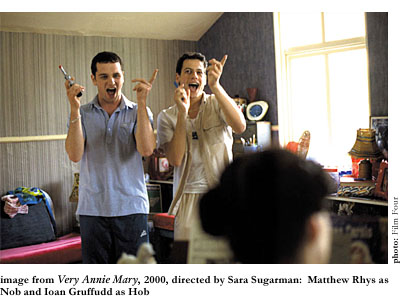

In supporting roles are Ruth Madoc as the evil stepmother to Annie’s Cinderella, and young hotshots Ioan Gruffudd and Matthew Rhys as shopkeepers Hob and Nob, who in addition to being Annie’s close friends and musical tutoring subjects are an openly gay couple in an accepting small town, which would be unique were it not for their grossly stereotyped portrayals.

Making her debut cinematic appearance in Very Annie Mary is Welsh folk songstress Mary Hopkin, who under the guidance of Paul McCartney in the late ’60s made waves with her lone hit, the enchanting “Those Were the Days.” Although Hopkin’s part is small and features no singing, her casting seems, perhaps unintentionally, to reinforce the notion of a singer who basked in the limelight long ago, and whose star has faded over time.

The real highlight of this small film, though, is Jonathan Pryce, whose fantastic and very human performance, particularly after his character’s debilitating stroke, is as convincing as anything he’s done, and truly draws on a great repertoire that includes everything ranging from Juan Perón to James Bond’s nemesis, from the seductive “Mr. Dark” in the film version of Ray Bradbury’s Something Wicked This Way Comes to the hapless anti-hero of Terry Gilliam’s existential dark comedy Brazil.

Very Annie Mary is writer/director Sara Sugarman’s second film, but first to be distributed in the U.S., thanks to a deserving screenwriting award won at the Sundance Film Festival. Sugarman started out on the other end of the camera, as an actress appearing in Sid and Nancy and on television. Released in the U.K. in 2000, Very Annie Mary stakes a claim for the blooming auteur in Sugarman, whose potential comes close to full realization in this well-made, assured, and thoroughly enjoyable film.

Very Annie Mary was the latest in this season’s screenings of the Key Sunday Cinema Club, which previews soon-to-be released films of note in the realm of independent and foreign cinema, and offers background and discussion of the films led by historians and scholars on a bi-weekly basis throughout the country. The Boston chapter currently has showings every other Sunday at the West Newton Cinema through December 16th.