Ernest Hemingway once described Paris as a “moveable feast,” suggesting that those fortunate enough to have spent their youth in the City of Light and cauldron of artistic revolution always carried a bit of its sensual, aesthetic, and hedonistic realities with them, enmeshed into their own beings. For Hemingway, Gertrude Stein, and others of that generation, Paris was the center—both physical and spiritual—of the art world. Fast-forward nearly a century and today’s art world can best be described as center-less—no one movement predominates and no one city can claim ascendancy in either the aesthetic or commercial life of the Contemporary Art market. New York, London, Basel, Dubai, Beijing, Hong Kong, Delhi, Buenos Aires—all these and more play crucial roles in the production, sale and collection of Contemporary Art. So, how to contend with such multiplicity? How to cope with artists, collectors, dealers, and auctions that are truly global in sentiment and scale?

The answer, considered enthralling and ingenious by some and superficial and disingenuous by others, is the art fair. Fairs bring Hemingway’s idealistic “moveable feast” into concrete being. They create, for a matter of only a few days at a time, a sensory, aesthetic, and commercial center around which the various forces of the art market converge, mingle, applaud, condemn, party, sell, and purchase, before packing up and moving on to the next fair, in the next city, creating the next temporary hub.

Earlier this month, it was New York’s turn to play host. In a two-week span, Sotheby’s set a new auction record for any work of art when it sold Edvard Munch’s The Scream for $119.9 million, and Christie’s set a new record for any Contemporary artwork, selling Mark Rothko’s 1961 canvas Orange, Red, Yellow for $86.9 million. Dozens of other artists’ and sales’ records were achieved at both houses, proving once again that in spite of the euro-zone crisis and generally gloomy financial outlook in other commodities markets, the art market is flush with cash and feeling bullish. Nestled in the middle of these events, and competing with various other fairs and exhibitions around the city, including the New Art Dealers Association, Verge, and the Whitney Biennial, was Frieze New York, the center-of-the-center of this record-shattering period.

Held from May 3-7, this was the inaugural New York offshoot of the wildly successful eponymous London fair. The UK version of Frieze, organized by Matthew Slotover and Amanda Sharp, has been setting up its tents in Regents Park since 2001. Known equally for its ability to attract blue-chip dealers from around the world and for evincing a commitment to emerging galleries, their artists, and non-profit projects, Frieze transformed the London art scene and is viewed as a leader in Contemporary fairs, second only perhaps to Art Basel on the yearly calendar, and with its own distinct point of view.

In 2012, Slotover and Sharp hope to capitalize on the success of their London flagship. In addition to the launch of Frieze New York, another new fair, Frieze Masters, dedicated to art created before the year 2000, will premier alongside the original Frieze in London in October. This expansion is both ambitious and timely. The current market is, against all odds, awash in cash and eager to spend it on top-notch inventory. Additionally, the market has become increasingly event-driven in recent years, as collectors and dealers alike flock to high profile fairs in the U.S., Europe, and Asia. The collectors receive VIP treatment and are feted at parties and dinners while simultaneously being provided with an overwhelming array of art from all corners of the globe, and in return the dealers gain wider exposure to potential new clients. By creating several successful franchises, Frieze will join the ranks of Art Basel and its subsidiary, Art Basel Miami Beach, in offering galleries and collectors several events per year, each with its own unique features, but which all carry the imprimatur of the Frieze brand.

The premier edition of the New York fair did not disappoint. Logistically, this was no small feat, as it was held on Randall’s Island, a rarely visited recreational area in the East River. Fair organizers arranged ferry service from downtown Manhattan and bus service from uptown. Both modes of transportation were included in the $40 admission fee. (For VIPs, there was also a fleet of BMW 7 series shuttles.) Once on the island, visitors were greeted by a massive, serpentine tent, three football fields in length. Designed by New York-based architecture firm SO-IL, the tent was remarkably airy, suffusing the interior in light and providing ample space for the over 180 galleries exhibiting within. These galleries were organized into three sections, including the main fair; Frame, dedicated to galleries founded less than six years ago and displaying a solo artist presentation; and Focus, which premiered at the New York fair and provided a platform for galleries established in or after 2001 showing up to three artists’ work. Although these special sections were grouped together and had differentiating signage, they were convincingly integrated into the main fabric of the fair, eliminating awkward transitions or a sense of segregation. The tent also provided visitors with several open, plaza-like spaces equipped with benches that helped to break up what could otherwise have been a tunnel-like, claustrophobic interior. Pleasant cafes and watering holes bearing such blue-chip New York names as Sant Ambroeus, Frankies Spuntino, and The Fat Radish dotted the periphery of the space, while food trucks and an outpost of the Standard Biergarten were located outside and provided only slightly more bohemian food and drink options.

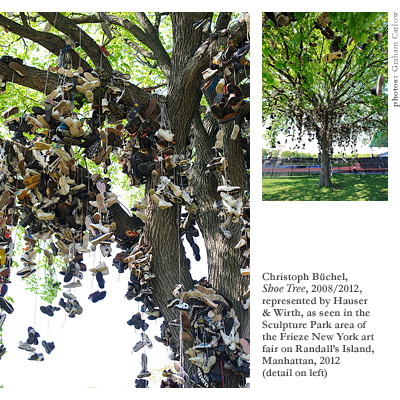

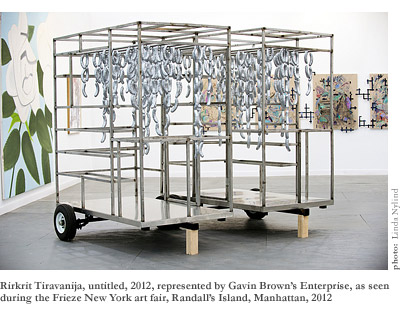

The Frieze Sculpture Park, which took advantage of the rolling green space of Randall’s Island and its beautiful prospect of the East River and Manhattan skyline, also awaited visitors who ventured outside. Featuring a number of monumental sculptures, the park was curated by Tom Eccles, Executive Director of the Center for Curatorial Studies at Bard College, and included works by Louise Bourgeois, Jaume Plensa, Subodh Gupta, and Joshua Callaghan, whose massive Pop-inspired Two Dollar Umbrella provided a witty reminder of the day-to-day realities of life in New York City. These works were all submitted for inclusion by participating galleries and were available for acquisition.

The fair also included a section of commissioned works, known as Frieze Projects. It was produced under the auspices of Frieze’s non-profit arm and was meant to highlight the organizers’ commitment to engaging with art beyond the reach of commerce. Curated by Cecilia Alemani of High Line Art, each of the eight Frieze Projects was intended to somehow address the relationship of art to its environment. By choice, seven of the eight participating artists displayed their works outside—only John Ahearn and Rigoberto Torres’ recreation of their seminal 1979 South Bronx Hall of Fame was, by necessity, located within the tent. Other projects included an open workshop for children hosted by Tim Rollins and K.O.S. (Kids of Survival) and a whimsical and incongruous field of tumbleweeds installed on a lush, green lawn by Latifa Echakhch.

One of the central critiques of today’s large fairs is that they allow little time, space, or solitude for serious aesthetic engagement. Although it is true that the narrow corridors and large crowds, not to mention the overwhelming quantity and variety of works on view, tend to limit the time one can spend with any given work of art, it is also true that certain pieces—or even entire booths—cannot help but arrest your attention. These moments will be different for each viewer, but for me it occurred first in front of a delicate, embroidered canvas by Egyptian artist Ghada Amer hanging in New York gallery Cheim & Read’s booth. Entitled White Bang, the piece was not only representative of Ms. Amer’s work, but also extremely beautiful—subtle female figures, embroidered in varying shades of blue thread, mingle with lightning-like filaments that swirl around the center of the white canvas, as though it were a vortex. Further examination of Cheim & Read’s presentation revealed equally striking works by Louise Bourgeois, Jenny Holzer, and Lynda Benglis. Gallery director Adam Sheffer told The Art Newspaper that the gallery had sold the majority of these works, including my beloved Amer, by mid-day on Friday. Other, similar moments occurred at David Zwirner’s stand, a tribute to the Minimalist movement featuring works by Dan Flavin and Donald Judd, among others. They, too, reported strong sales totaling $2.13 million by Friday.

On the ferry ride back to Manhattan, I struck up a conversation with a woman who asked me what I had seen that I liked. After I waxed poetic about my favorite objects, she sheepishly confessed that she had not noticed any of them. When I asked her the same question in return, she launched into an equally flowery recital—I hadn’t noticed a single one of the pieces that had enthralled her. And this, perhaps, is the beauty of the fair—there is truly something for everyone. That it is all for sale, for those lucky enough to be in a position to buy, is just the icing on the cake. The rest of us are free to look, admire, and form our own opinions.

The trepidation and outright disdain with which many view the vast sums of money spent on art speak to the difficult and contentious financial times in which we live. It seems that globally the haves and have-nots are moving further and further apart. That anyone should have $1 million—let alone $120 million—to spend on something as frivolous as a work of art seems wrong, somehow, when so many others are out of work and finding it harder and harder to live in even the same level of comfort their parents were able to provide for them just one generation ago. And yet, art, money, and power have always been intimate, if ambivalent, bedfellows. The wealthy have always been the patrons of the arts, and although this has sometimes led to appalling censorship, it has also left us with monuments as rich, varied, and culturally important as the Taj Mahal and Sistene Chapel. To write off today’s collectors as nothing more than trophy-hunters is to deny the history of collecting and patronage of the arts. Were Peggy Guggenheim alive today, she would undoubtedly have been an active and acquisitive visitor to Frieze. And who is to say that any of the many collectors in attendance could not prove to be the next Guggenheim or Frick or Gardner or Getty? Only time will tell which of the many artists and artworks represented at Frieze make it into the canon, but one should at least applaud the risk-taking collectors and connoisseurs who are on the cutting-edge, making aesthetic judgments and building what they hope will be lasting monuments of visual culture.

Frieze has now packed up and left town. The tent has been dismantled, the artworks crated and shipped to new owners, or if unsold, to the next stop on their gallery’s list of fairs. Gallerists and their staff will tally the inventory lists and book their tickets to the next venue. Nomadic collectors will do the same. This is the heady dance of the current market—to serve its global constituency, the market must be constantly on the move, seeking out new settings, new outlets, and new centers. That it does it with panache and very few apologies may make it an easy target for those looking to expose the extravagances of the super-wealthy, but it also makes for one hell of a sensory feast. And if you look closely—beyond the parties and BMWs and spectacle—there is even a great deal of wonderful and important art to be seen.