Meeting Purpose: 2nd Annual Boston Theatre Community Town Meeting

Sponsor: StageSource

Host: Huntington Theatre Company

Date: 19 June 2000

Topic: How do we increase visibility and support for theatre in the Greater Boston area?

The atmosphere in the Boston University Theatre (known to theatre-goers as the Huntington) is just a bit dark for such a cool and sunny evening in mid-June, and not just because it’s Monday, the day after the Huntington’s 1999-00 season ends. And not just because the set of August Wilson’s only moderately well-received new play-in-progress, King Hedley, is still up, backdropping the stage, a jumbled wreck of bleak brick tenements with barred and boarded windows, a beaming black ballplayer in a baseball cap pentimentoed in white commercial stencil-paint on one of the crumbling walls. It’s dark because a couple hundred people from the theatre (which no one seems to spell “theater” anymore) community have gathered at the second annual town meeting, and underneath their giddiness they fear that with a downturn in the economy their stages might fall into as much disrepair as the Pittsburgh neighborhood of Homewood that’s depicted in Wilson’s play. They are here to figure out why the audience for theatre in Boston isn’t booming like the construction and education businesses are. Shouldn’t the growth of this entertaining enterprise be commensurate with the wealth of the wealthiest citizens, the way it was in Periclean Greece when the sale of olive oil and wine made leisure-time conducive to philosophic reflection and artistic activity? Could Tom Cruise and Tom Hanks have numbed and dumbed us down so far with their movies that we have no energy left for the sort of catharsis that comes from great characters exchanging the poetic lines of a brilliant script?

It doesn’t take long for the lively people here, who after all are trained in the power of suggestion and illusion, to forget about the possibly very dark destiny of American art and to lighten the atmosphere with ribaldry and wit, making sure the gloom of Wilson’s set doesn’t dominate the dialogue. (Many of them probably adore the giddiness-galore of Broadway frivolity more than the tragic gore of Shakespeare anyway.) For openers, John Kuntz, winner of the most recent Elliot-Norton Award for best solo performance, gets the place roaring with his campy send-up of a theatre queen fussing and gossipy about the pratfalls of the theatre life. The names he drops in his outrageous monologue, while flinging that tacky black synthetic boa over his slender shoulder, break into guffaws from the cognizant crowd. “Why did I fall in love,” he wonders at one point, “with this beast they call the theatre!?”

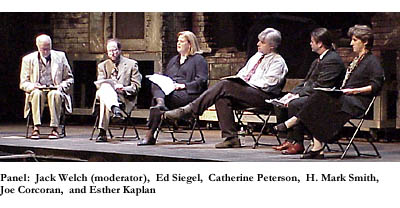

The answer to that question does not remain open to discussion—he doesn’t strut or fret for more than 10 minutes upon the stage, but walks off to hoots and hollers. Now out comes Michael Maso, managing director of the Huntington Theatre and self-described “groupaholic,” to welcome the crowd, to recognize aloud that the local theatre audience really isn’t growing much, and to introduce Jack Welch, managing director of Baker’s Plays and founding member of StageSource, the sponsor of this second annual town meeting. Welch, no show-off, tones the atmosphere down, and wastes no time turning the evening over to the five panelists, each of whom will be given five minutes to address three sequential questions whose answers should give the theatre some direction and inspiration. What is your organization doing to widen the Boston theatre audience? What is the biggest obstacle you face in accomplishing the task? What can the good-intentioned and civic-minded members of the audience do to help your own particular part of the cause?

First up is Catherine Peterson, the executive director of Arts/Boston, the high-profile outfit responsible for (1) the BosTix discount day-of-the-show clearinghouse outlets, at Copley Square and Faneuil Hall, that are popular with tourists and office-workers alike, she notes, and (2) the Arts Mail discount vendor of surplus advance-sales seats at, for example, the Lyric Stage and the Leland that otherwise would probably remain empty. Peterson proudly proclaims Arts/Boston’s success in “helping to build relationships” between theater groups and new audiences, saying (if my tape recorder can believe its ears) that the organization sells three million dollars worth of tickets per year. She notes—or gloats—that influential Boston Phoenix critic Carolyn Clay uses Arts Mail as a resource for small-theater productions. “Space,” she says in response to the second question in the sequence, is a big problem facing Boston theaters—lack of it, she probably means; especially downtown, where (for some related reason) blockbusters like The Greatest Story Ever Told can’t afford to stay on more than a couple of weeks. “Make sure you’re on our mailing list,” she reminds the crowd with the clock ticking down. “We want to be your advocates.”

Ed Siegel, the first-string theater critic at the Boston Globe, announces that he personally reviews more plays each year and that the other papers in town do, too. He advises the audience to read Maureen Dezell’s “Stages” column in the Globe, bound to be of increasing importance to ticket sales for small and large Boston theaters alike. He questions whether he and his employer, as evaluators of the cultural scene, are obligated to help theater companies that can’t afford to advertise. “Our readers,” says Siegel, “are our first, second, and third priorities. It’s not my job to sell theaters,” he continues. “Boosterism based on someone’s intentions,” he elaborates, “can only lead to a loss of credibility. My responsibility is to bring excellence to the attention of my readers,” and to tell them whether they should spend their time and money on given productions. (“Fortunately,” he adds, “the answer increasingly is yes, they should!”) And yes, the Globe can do more to help, without selling out and giving thumbs up to everything. If there were more of an audience for the plays, it would be possible to have a second full-time theater reviewer. More listings would be nice, too. Plus the thorough kind of coverage given the Red Sox and the presidential campaign. “The better the productions,” he starts to conclude once the applause for some of these dreams dies down, “the better the case I could make for such coverage.” And to make these dreams come true, why not—for one thing—give more “edge” to the small and mid-sized theaters in Boston and stop playing it safe? Do good new stuff like Quills, Killer Joe, or Some Explicit Polaroids.

Given their prominence in the theatre community, Peterson and Siegel are hard acts to follow. But there’s more to come. H. Mark Smith, program coordinator for the Massachusetts Cultural Council; Joe Corcoran, CEO of TheatreMania.com (or TheaterMania.com); and Esther Kaplan, special assistant to the mayor for cultural affairs for the City of Boston—they have something to say as well.

Smith speaks shrewdly of the effort to raise the consciousness of the “noncultural community”—i.e. the effort to form partnerships between wealthy but middlebrow corporate sponsors and the small theaters that could really use their enormous piles of not necessarily all-that-well-deserved money. A state-agency bureaucrat with a big heart and a keen mind, he encourages the crowd to lobby politicians for public support of theater arts, and he praises the practice local theaters make of hiring Equity actors.

Corcoran uses his five minutes partly, and understandably, to plug his Internet theater resource company, saying it offers reviews, calendars, profiles—the works—free of charge and in a format convenient to those (such as tourists) in search of a condensed, quick-check guide to the plays currently in production in the greater Boston area. “The benefits” of his online service “should be obvious,” he says, to theater companies that buy advertising space on the TheatreMania.com Web site. “TheatreMania dot com” (he keeps repeating the name of the outfit, for good reason) “is eager to play a part” in broadening the theater audience.

In a sense, Peterson, Siegel, Smith, and Corcoran are in a position to understand why the mainstream middle- and upper-middle class (okay, and the downright filthy rich, too) are not driving back into town, with the doors of their air-conditioned cars locked and their windows rolled up, to go to the Leland, the Open Door, the Lyric Stage, and not even in very great numbers to the A.R.T. in Harvard Square and the Huntington right here across from the much more broadly beloved Symphony Hall. (They never do pontificate about the pervasive American anti-intellectual suspicion of those who are “different” the way they could if this were happening at the A.R.T. and Anna Deveare Smith and Robert Brustein were here, with Brustein’s best friend, ha ha, August Wilson.)

Esther Kaplan, on the other hand, is in a better position, in her office down at City Hall, to understand the feelings of alienation, by class and taste, and the externally imposed frugality (let’s not call it poverty, please) that keep the crowds from Dorchester from donning their duds and jumping on the Red Line to the theater district on weekends. She doesn’t really go into it, though. (This is turning out to be much more of a marketing meeting than a philosophical symposium, isn’t it?) She’s here with the facts and figures from the Mayor’s office. Reporting on a Menino-mandated study of “the cultural community’s needs” and how best to fill them, she says her crew of researchers interviewed 50 “cultural leaders,” 25 city officials, a bunch of public and private funders, and held 13 community meetings in an effort, she said, to find out how “to strengthen the fabric of city life” through vital cultural activity. In textbook good-government style, she enumerates the eight areas to work on, including economic development, in-school and out-of-school opportunities, access to “cultural opportunities,” attention to “cultural infrastructure,” dissemination of “cultural information,” financial and technical support, and management of public art events. Her earnestness, together with the noble intentions of her office’s work, keeps the audience from falling asleep. Is everyone musing on the massive amounts of street theater we could have in Boston if her flowcharted dreams of diversity came true in segregated Boston? Or is everyone wondering why she bothers to even hope that, say, serious live drama will someday soon be such a popular form of culture that the price of admission to a play will be roughly equivalent to that of a movie ticket?

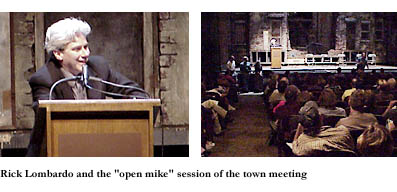

Following Kaplan’s presentation—but before the radically abbreviated keynote speech by Ben Cameron, executive director of Theatre Communications Group—several conscientious citizens take the opportunity of an open mike to offer their own observations and suggestions. One person suggests hiring a marketing firm to assess the whole situation and offer a solution. One wonders how to improve the image of the theatre community in the funding community. And more than one, in response to Esther Kaplan’s presentation, asks how the theatre community, with the help of the funding community, could do outreach (or inreach) to the minority community in a city that ranks 42nd, of the 50 largest American cities, in public funding for the arts—pretty far behind Philly and D.C., which both have significantly larger African-American communities, way way behind San Francisco, and not even in the tailwind of New York.  We should take the Long Wharf Theatre in New Haven as a model, says one panelist. They diversify their casts and their audiences (and presumably their repertoire). The Boston Shakespeare Company’s summertime productions on the Boston Common do that, notes another panelist. People who won’t go to the A.R.T. to see A Midsummer Night’s Dream will go to the Common to see it, partly because it’s free and outdoors and easy to get to, no doubt, partly because the cast is culturally diverse, partly because the productions are a delight. Yet another panelist says he saw kids whooping it up recently at a production of East Is East at a theatre in the rough East End of London! There’s the Underground Railway Theatre at the Strand Theater in Dorchester, isn’t there? And doesn’t someone else say the Wheelock Family Theater over there in the Fens is a beautifully utopian place in this regard?

We should take the Long Wharf Theatre in New Haven as a model, says one panelist. They diversify their casts and their audiences (and presumably their repertoire). The Boston Shakespeare Company’s summertime productions on the Boston Common do that, notes another panelist. People who won’t go to the A.R.T. to see A Midsummer Night’s Dream will go to the Common to see it, partly because it’s free and outdoors and easy to get to, no doubt, partly because the cast is culturally diverse, partly because the productions are a delight. Yet another panelist says he saw kids whooping it up recently at a production of East Is East at a theatre in the rough East End of London! There’s the Underground Railway Theatre at the Strand Theater in Dorchester, isn’t there? And doesn’t someone else say the Wheelock Family Theater over there in the Fens is a beautifully utopian place in this regard?

Mayor Thomas Menino’s not known for connoisseurship—he’s the guy who two years ago on the Boston Common could be heard introducing, unless the breeze was really playing tricks with his words, “Sergio Ozower and the Tanglewood Tabernacle.” But he does seem to understand the importance of improving the quality of life in crowded, run-down neighborhoods. People from East Boston, Charlestown, Roxbury, Dorchester, and other solidly working class (or not-working class) neighborhoods may go in modest numbers to family-oriented productions of the Nutcracker and Broadway imports like Cats. But their real potential is in grassroots theater produced by schools and community centers. This much is easy to gather.

It’s dark outside by the time the evening ends, though not as dark as it is inside now that the season’s over and everyone’s gone home.