As soon as I emerged from the abject bunker that is South Station, into the windswept desolation of Sunday evening Fort Point, I began to have my doubts. True, I said to myself, the Theatre District is over-reviewed and overrated, but at least it doesn’t make you feel like you’re the only person to have survived a nuclear holocaust. And, on reflection, I would have quite liked to see As You Like It.

But the eerily deserted staircase that led up to the fourth floor of the Actors Workshop on Summer Street could hardly have felt farther removed from its lavish ceremonial cousin at the Wilbur Theatre. As for the black-walled, overheated theater itself, there were only about a dozen people present when I arrived. Nevertheless, the only spare row was the front one, so, never understanding why so many people seem allergic to front rows, I took my seat there. Yet I regretted my boldness as soon as the lights went down and the evening’s performers came onto the stage shrieking, gurgling, skipping, and scurrying like the guests at an asylum Christmas party. “Oh no,” I groaned, “It’s going to be one of those shows.” Past experience told me it was only a matter of time before one of the inmates hauled me onto the stage and tried to pull of my pants.

To be fair, I oughtn’t to have been greatly surprised. After all, I was attending the latest show by Boston’s little-known Performance Cult. And didn’t that name reek of the worst excesses of thespian exhibitionism normally reserved for “workshops”? (A British comedian once remarked that anyone who uses the term “workshop” and who is not connected with light engineering is—if you’ll pardon my Old German—a twat.” If I remember that line it is because I have some sympathy with it.) Yet, at the same time, I was also attracted by Pcult‘s “simple” concept, described on their Web site: to present a one-off show, each entirely unique, consisting of a series of brief, original “vignettes” in whatever medium the performer chooses—whether that be drama, song, dance, music, puppetry, mime, or poetry. And I was intrigued by the stipulation that all of these pieces were to be “based on the truth.” What, I wondered, could that mean in practice?

The first piece, into which the actors launched once the asylum party was over, gave some clue. Standing in a line across the stage, they took it in turns to step forward and start to say something, before being interrupted by the next person—usually before they had even finished their first sentence. The effect was rather like walking down a busy street and listening to the snatches of conversation that meet your ears as the people stream past. It was hardly profound, nor particularly amusing, but as an emblem of what was to come it worked well enough.

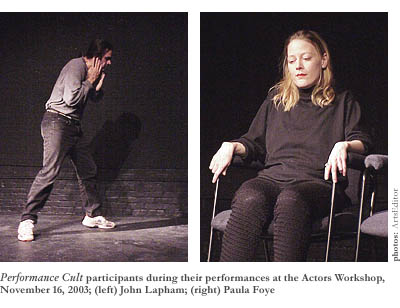

The only problem was that it was better than most of what followed. The first solo piece, performed by John Lapham, began with an overly long repetition of his asylum routine. Finally, after yelling a few words in what sounded like Russian, he calmed down and, donning his spectacles, launched into a faltering, almost apologetic explanation of how all this sound and fury was part of an ongoing process of working out the “fears” that had been with him ever since, at the age of nine, his uncle had scolded him for singing “oh my delicious hamburger relish.” Yes, there was the occasional funny (apparently improvised) line here, but most of Lapham’s anguished sentences trailed off into silence before the thought that gave them birth had been coherently articulated. It was hard to tell how much of his angst was acting; certainly he looked genuinely terrified as he prepared, at the finale of his piece, to sing a song “without shame, to fill the space I am in.” And, though the song was quite pretty (in a cheaply sentimental way), I couldn’t help concluding that it must have been more personal demons than artistic judgement that convinced him to sing it to us.

There was also more than a whiff of demon exorcism about the next piece, performed by Paula Foye. She began by informing us, rather bitterly, that she works as a textbook proofreader, taking the assignments (such as math books) that her co-workers don’t want. She was going to share with us, she continued, what she had been thinking about recently, as she sat in her gray cubicle. Yet rather than launching into a story illustrating the alienation of man in the modern capitalist jungle, all we got was a haltingly improvised story about her ex-boyfriend, a former Mr. Junior America with occasional anger management problems. Again, this story had its amusing lines (especially one about the boyfriend openly stealing a hamburger from a roadside diner because he believed that if you work on your body then you don’t have to follow the same social rules as everybody else), but not enough to salvage it. A glance at Foye’s bio confirmed that improvisational storytelling is her way of “purging her pain.”

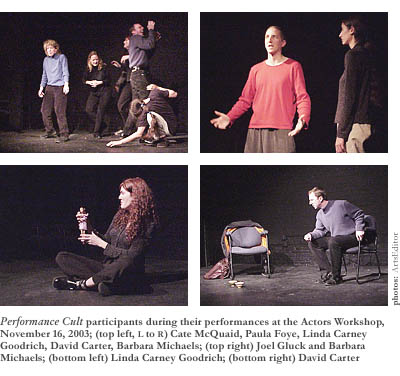

However, just as I was ready to write off Performance Cult as a drama therapy group with the gall to charge an entrance fee, along came David Carter. Sure, even he believes in “theater for personal change,” but at least he managed to create a little dramatic illusion. Indeed, illusion was the operative word in his piece when we learned that the apparent partner, about whose parasitic idleness he’d just been bitterly complaining to his psychiatrist, turned out to be his cat. True, the joke was rather labored, and it certainly took too long to set up, but at least I was able to uncurl my toes a little while a comically intense Carter had it out (at his psychiatrist’s insistence) with the hapless creature.

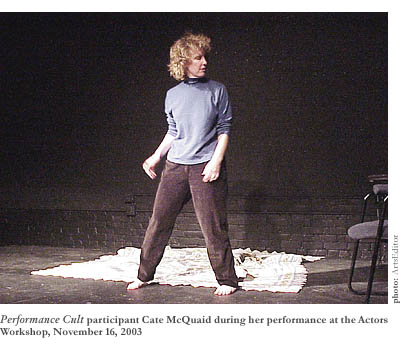

Next up was Cate McQuaid, visual art critic for The Boston Globe. Hers was an amusing, vividly evoked farce in which an impotent ex-boyfriend appeared in her bedroom, persuaded her husband to take a shower, and then proceeded to take off his clothes and rub up against her erotically before finally being persuaded to leave. As he went, he declared that “impotence is fun,” upon which McQuaid’s husband returned and got into bed with her, McQuaid reassuring him that nobody was saying he was impotent. I presume that the piece was supposed to have something to do with men’s inability to face up to impotence, but the precise point it was trying to make (if there was one) remained obscure.

Last up was Joel Gluck, co-founder of Pcult. His skillfully delivered narrative, detailing the final months of his doomed marriage, had a clarity and emotional intensity missing from what had come before. The piece was made all the more vivid by the motif of his wife (played by Barbara Michaels) standing next to him all the while, staring at him with a mixture of accusation and entreaty, repeating the urgent mantra “I need you to move out now.” The moment at the end of the piece when Gluck finally turned to her and whispered a final “goodbye” was deeply moving.

There was also one other participant, Linda Carney Goodrich, who performed brief little skits between the other performances. Her theme was her recent childbirth—or, more precisely, the body issues that childbirth raises for women. For example, her first scene involved Barbie—a rather obvious symbol of supposedly perfect, impossibly slim female beauty—giving birth. After the baby was “born,” the plastic belly that had enclosed it was thrown aside, while Goodrich screamed like a South Boston fishwife that now you couldn’t even tell Barbie had had a baby. The next scene trod similar ground, involving three new mothers (including Barbie) insincerely exchanging assurances of how great each other looked, before competing with tales of how awful they nevertheless felt inside. Then, after an agonizing birth scene, there was the startling scene in which a naked Goodrich stared down at her dimly lit body, wailing that it would never be the same again.

In all of these scenes there was the sense that a body marked by motherhood is something to be ashamed of. But then we were treated to the contrasting scene, perhaps the highlight of the evening, in which Goodrich perched pertly on a stool, like a voluptuous cartoon vixen, one proudly maternal breast liberated from her red bra and attached to an electric breast milk extracting machine. To a soundtrack of ’70s lounge music, she writhed seductively, hilariously, uttering lines like “admit it: it excites you” until, reaching a climax of womanly pride, she drank her own breast milk (although she actually drank an emergency, pre-extracted supply, apparently being too nervous to lactate onstage). If only she had left it there instead of returning one more time for a rather obvious scene in which she argued with her partner about who would look after the baby when it woke up.

Perhaps the point was to return us from theatrical fantasy to everyday reality. For, taking the evening’s performances as a whole, one could be forgiven for concluding that this was the “truth” that Pcult was seeking to illustrate—a naked reality shorn of all theatrical artifice. But surely this realist philosophy of theatre had its day a long time ago. After all, isn’t all theatre supposed to be about “the truth” (or, more grandly, “the universal truths of the human condition”)? Yet being about the truth needn’t entail taking the craft out of performance, the art out of writing. Indeed, as Joel Gluck’s piece amply demonstrated, theatre best conveys the truth when it raises its audience above banality and cliché, thereby exposing them to the true significance of life’s events. If all we wanted to hear was mundane anecdotes and half-baked jokes, ill-formed sentences and half-expressed thoughts, we could have saved ourselves nine dollars and stayed on the T.

To be fair, I think the “truth” Performance Cult is actually trying to articulate is not so much artless reality as the personal experience of the performers. The problem is that too many of the performers seemed incapable of turning their personal experiences into artful, engaging theatre. Nor, perhaps, did they even want to—as I mentioned above, the primary aim of most of them seemed to be more personal improvement than artistic achievement. Hence, it came as no surprise to learn after the show that Joel Gluck (the co-founder of Pcult, remember) is currently studying to be a drama therapist.

Not that I have anything against drama therapy. But it seems to me that if you are going to charge members of the public good money to watch a show written by the performers involved, there needs to be some fairly rigorous peer reviewing of what ends up in that show. Rehearsals need to be more than—as they are at the moment—just opportunities for performers to request feedback if they feel sufficiently psychologically robust. They need to be times when some serious, honest quality control is imposed on the performers, when pieces not up to scratch are either ditched or rewritten. There has to be some kind of minimum standard, both of writing and performance.

It is only fair to emphasize, once again, that each Pcult show is entirely unique. Perhaps the show I attended was a particularly unsuccessful one. Moreover, one can only applaud the energy and commitment that goes into making such independent shows a reality—especially in the current arts funding crisis. But, all things considered, I still wish I’d gone to see As You Like It instead.