A camel, joked Sir Alec Issigonis, designer of the perennially popular Mini automobile, is a horse designed by a committee. Attending the panel discussion regarding the proposed Rose Kennedy Greenway at the Boston Public Library in early February, one caught more than a whiff of how such a malproportioned beast can come to be.

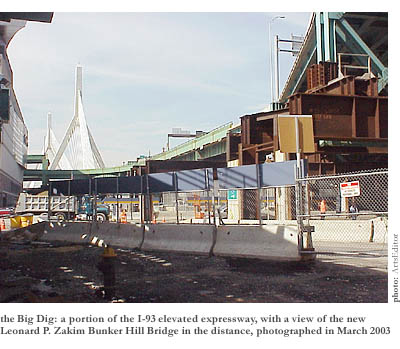

But first the background. Those who have been living in a hole in the ground for the past decade ought to be informed that they will soon be able to drive their cars through a much bigger hole in the ground underneath the current I-93 elevated expressway through downtown Boston. This will allow that ugly, crumbling piece of town-planning insanity to be demolished, thereby freeing up an eight-acre corridor of land between the North End and Chinatown. Now it is time to determine what to do with that land.

Everyone seems to agree that this decision is a momentous one, described on Boston.com as “the biggest urban design issue in Boston in decades.” And public interest is accordingly feverish, if the packed-to-the-rafters (or, rather, to the first-floor ground-slab) library auditorium is any indication. Not a seat was to be had as the various mutually backslapping suits finally handed over to the panel of architecture and design professionals; numerous relative latecomers had to make do with the exhibition of preliminary designs mounted in the lobby outside.

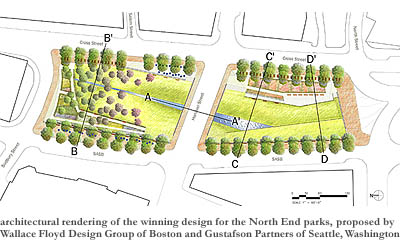

In fact, for all this show of seeking public feedback relatively early in the design process, we soon learned that certain decisions had already been taken by the planning committee behind closed doors. The most crucial of these was the admittedly laudable decision to designate the land for public spaces—a “Rose Kennedy Greenway”—rather than, as one might have feared, a shopping mall or yet more luxury apartments. Less obviously wise, however, was the decision to divide the long, thin plot into three distinct regions—the North End, the waterfront, and Chinatown—for which independent design contracts have already been awarded (a small amount of land having also been reserved for a botanical garden). The panel wondered aloud whether it would have been better to have entrusted the design of the whole greenway to one design group with a single unifying vision for the whole project—the kind of unifying vision that results in horses rather than camels.

The panel was also unanimously dismayed by the apparently irrevocable decision to sandwich the parks between sidewalks (for which the street furniture has already been ordered), needlessly reducing its mere six-lane width even further. They might also have lamented that the planning committee has elected to preserve all existing roads beneath the expressway. The result is that the greenway will be hemmed in between Purchase Street and Atlantic Avenue, and criss-crossed by any number of smaller roads heading into Haymarket and the financial district. Hence, the three distinct greenway parks will be further subdivided into eight road-lined rectangles, which the official literature refers to as “parcels.”

As for what is to be included in these parks, the panel did a good job of highlighting the complex range of issues with which the respective designers must grapple. Take the two-parcel North End park. Should it be a park for local residents, for Bostonians in general, for tourists, or for all three? Should it be a tightly designed piece of landscape art, or should it be a more flexible, utilitarian space—or perhaps a more traditional, pastoral kind of place? Relatedly, who should it try to cater to? Idlers? Walkers? Skateboarders? Basketball enthusiasts? Should it be designed with a summer day or a winter night in mind? Should it embrace the North End’s brick-paved past, or should it look to the future and attempt something entirely new? Or should it perhaps try to commemorate the North End’s Italian present?

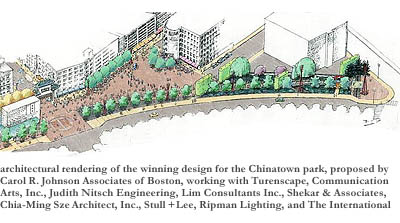

Quite what that latter option would involve is unclear. One hopes that it would not cross anyone’s mind to erect a miniature leaning tower of Pisa—although we ought not to be too sanguine about that; a number of the preliminary designs for the one-parcel Chinatown park include dragons and chopsticks. To me the resort to such obvious iconography is as unnecessary as it is tacky. Erecting a gateway consisting of two giant chopsticks makes a park no more authentically Chinese than filling a pub full of Guinness posters and pseudo-historical junk makes it authentically Irish. (A friend of mine from Dublin once complained that he couldn’t have had a less Irish experience than when he found himself in one of Boston’s numerous bars beginning with the letter “O.” After being asked for ID every time he wanted a drink, he was finally thrown out for being drunk and a little rowdy. It was St. Patrick’s Day.) As the panel suggested, if the Chinatown park designers really felt the need to incorporate a Chinese theme, they would do well to settle for planting some Chinese trees and leaving it at that.

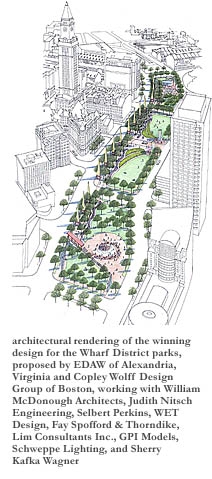

The biggest section of the greenway, consisting of five parcels, will be the waterfront section. The ambitious design brief here is for this (ahem) flagship park to reunite the city center with the ocean, from which it has been cut off for so long by the expressway. Again, that aim has been interpreted rather literally in one preliminary design, which involves simply flooding the five parcels with water. As the panel pointed out, such aquatic schemes can be extremely successful, as at the Christian Science Plaza, or utterly disastrous, as at Government Center. Personally, although a series of waterfront ponds might make for great skating in winter, I don’t see the point of them when the harbor is so close. I tend to think the designers should dream up something more imaginative to signpost people there.

In the end, though, I can’t help feeling that all this earnest soul-searching about what to do with the waterfront parcels is a little excessive. After all, the park will occupy only five acres in what is a decidedly ugly part of the city, overlooked by the various anonymous towers of the financial district on one side and by the postmodern monstrosity that occupies the Rowes Wharf on the other. Rather than enhancing the charm of the park, as it does along the similarly proportioned Commonwealth Avenue Mall, the surrounding architecture will seriously detract from the appeal of whatever is built on the waterfront site.

Moreover, reuniting the city with its waterfront is a dubious motive at best when that waterfront is such an undesirable place to be. Having only moved to this city a couple of years ago, I remember how bitterly disappointed I was when I first summoned up the courage to scurry under the forbidding expressway and across Atlantic Avenue to take a look at Boston’s famous harbor. My heart sank faster than a tea-chest tossed overboard when I first set eyes on the featureless desolation that is the Wharf area: the gigantic slab of mediocrity that is the Marriott hotel on Long Wharf, the monstrously ugly multi-story car park on India Wharf, and the curiously cobbled together aquarium building on Central Wharf.

Of course, this state of affairs is not set in concrete (or, indeed, brick)—positive miracles of urban design are possible given the requisite amount of political will. Take Barcelona in Spain—another city that unaccountably turned its back on its waterfront during the latter half of the Twentieth Century. Under the leadership of inspirational mayor Pasqual Maragall and boosted by the impetus of the 1992 Olympic Games, Barcelona has undergone an extraordinary transformation during the past 20 years, wholeheartedly re-embracing the sparkling Mediterranean via the construction of a whole new waterfront district that includes housing, restaurants, shops, a new harbor, and two huge towers. Nor should I neglect to mention the thousands of tons of sand that were shipped in to create a large public beach. Such is the quality of the design that has gone into these new developments that Barcelona has become the most popular city in Europe to visit and arguably the most beautiful city in the world.

It seems to me that Boston needs a similarly grand vision of waterfront revival if it is to fulfil its potential to join Barcelona in the ranks of Great World Cities. However iconic the greenway project becomes, it cannot single-handedly redeem the legacy of decades of architectural calamity and mediocrity. But, alas, one can’t help but be pessimistic about the prospects of such a revolution taking place when even the parameters of the greenway project itself are so conspicuous by their lack of boldness, confining the parks to a series of glorified traffic islands.

It seems to me that Boston needs a similarly grand vision of waterfront revival if it is to fulfil its potential to join Barcelona in the ranks of Great World Cities. However iconic the greenway project becomes, it cannot single-handedly redeem the legacy of decades of architectural calamity and mediocrity. But, alas, one can’t help but be pessimistic about the prospects of such a revolution taking place when even the parameters of the greenway project itself are so conspicuous by their lack of boldness, confining the parks to a series of glorified traffic islands.

For what it is worth, I would go much further than the panel in challenging those parameters. Not only would I abolish the sidewalks and hand the whole project to a single designer, I would also do away with one or both of Purchase Street and Atlantic Avenue and replace them with a cycle lane. This would have the effect of both minimizing the noise and fumes of traffic (thus making the greenway feel more park-like) and symbolizing a more environmentally conscious future in which car use is kept to a minimum—a genuine green way. Bringing the park right up to the surrounding buildings would also allow those buildings to play their role in the scheme, perhaps by becoming terrace cafés or restaurants. In addition, I would abolish as many of the cross-streets as is feasible; it seems to me that we need as much cohesion as possible in what is already a highly fragmented part of the city.

As for the question of what to do with the park itself, I rather like the idea of a walkway—possibly the boardwalk which features in one preliminary design—along which people could stroll in the summer evenings. I also like the idea, suggested by the panel, of the walkway’s rising and falling to provide a variety of perspectives on the surrounding area, making up for the loss of the view from the elevated highway. On the other hand, given the low quality of many of those vistas, perhaps it would be as well to screen the walkway with as many trees as possible, as suggested by an alternative preliminary design.

Finally, let me wholeheartedly endorse two pleas that the panel made in its closing remarks. First, that whatever is built should be properly maintained. If there is any criticism to be made of the Barcelona authorities, it is that they are focused too much on building new things and not enough on preserving what is already there. It is not uncommon to see a new building or installation crumbling and blighted by graffiti within a few years of completion.

Second, let me urge the members of the planning committee not to further tie the hands of their chosen designers by requiring them to consider too many of the above-mentioned users, needs, and aspirations at once. Such a compromising attitude might constitute the path (or boardwalk) of least political resistance, but it would also be the surest way to guarantee that Boston ends up with a lumbering camel when what it needs is an oasis of design, around which the surrounding urban desert can be reclaimed for humanity.