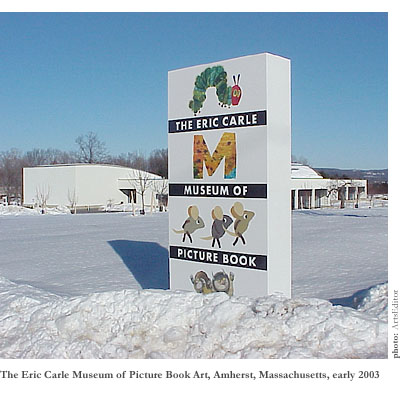

There are a lot of things besides the west, central, and east galleries to like about the Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art, not least of all its location. A low-slung, inconspicuous, off-white, International Style building, with five or six pretty gray dormers protruding from the roof, the museum sits next to an orchard on the spacious pastoral property of Hampshire College, on the southern side of Amherst, Massachusetts. For pure architectural aesthetics, you couldn’t ask for more—less, in this case, definitely being more. All clean right angles, opaque panels, and transparent windows—it goes well with the rest of the alternative college’s neat clusters of tidy buildings.

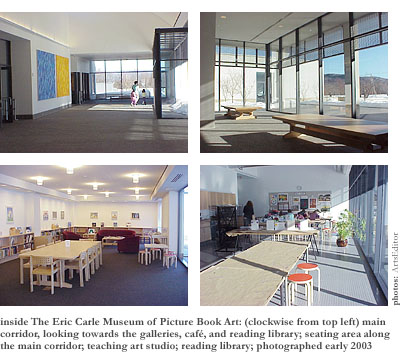

It’s not bad inside either. The galleries of the museum, dimly-lit to preserve the original works on display there, offer views of another sort. Dedicated to exploring the role of visual art in international children’s literature, the founders of the museum—among them Director H. Nichols B. Clark—have opted to use the place to showcase the art-making process. Rather than display the finished picture books themselves in cases on the wall (an absurd proposition), they’ve framed the original art from the illustrators’ studios and mounted the pieces—sketches, end papers, layout dummies, and all—the way they would artwork in any ordinary fine arts museum. A box on a bench in each of the three galleries contains copies of the corresponding books that the studies eventually turned into. A drawing on the wall is to its book on the bench as a chrysalis is to a butterfly.

If it weren’t for the accessible picture books themselves, you get the feeling that children would have no reason to visit the galleries, that they’d be better off heading for the museum’s reading library or teaching art studio, or toward the next educational presentation in the 130-seat auditorium. The original works are all mounted well above the head of your average six-year-old, after all. But because the books are available, and because the children’s own personal grown-ups are there to help them appreciate the place, they do run, to some extent, from frame to frame, just the way you’d hope, some of them carrying art-appreciation question-and-answer checklists composed in accordance with the practical yet dynamic Visual Thinking Strategies devised by Abigail Housen and Philip Yenawine. Ambling in their first few months of autonomous mobility, or sliding giddily across the polished floor in their socks, toddlers in purple overalls and their older siblings in blue jeans look up to the wood-framed pictures with considerably less ponderous faces than their parents do. But their parents are far less somber than they would be in a fine arts museum. The most reticent people here seem to be the art-school students with orange hair and Japanese animation t-shirts going face-to-face with the individual pieces, and even they wear bemused expressions on their admiring, euphoric faces.

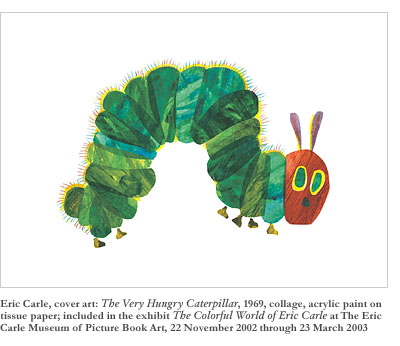

As the name of the museum would suggest, Eric Carle is one of the motivating forces behind the novel new museum, which opened late in November 2002. (According to Director of Development & Marketing Nora Maroulis, the ECMPBA, as the museum may never be known, has already welcomed eighty percent of the 25,000 visitors expected in a year.) Author of some 70 children’s picture books, Carle is most famous for his 1969 book The Very Hungry Caterpillar. He and his wife Barbara Carle conceived of the museum years ago. Only with the help of Hampshire College have they been able to take the concept through all stages of metamorphosis. Perhaps they are to the museum as the very hungry caterpillar is to the butterfly, eating its way through the beautiful little book—starting with leaf matter, progressing through one apple, two plums, three raspberries, and so on, and graduating to such delicacies as ice cream and sausages—until, gorged in pupahood, it begins to eat its way out of its own cocoon. The Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art couldn’t have fluttered from the cocoon until it had gone through all the motions. But it’s a colorful butterfly now—a swallowtail or a monarch—in a sometimes not very colorful world.

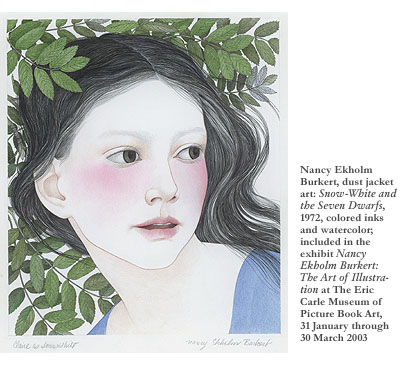

Not surprisingly, the three atmospheric galleries of the museum feature not only rotating exhibitions of original work by well-known illustrators, but also, and always, the work of Eric Carle himself. Through March 30th, the work of Nancy Ekholm Burkert will be on display. Known for illustrations of Snow-White and the Seven Dwarfs and of Roald Dahl’s James and the Giant Peach, Burkert will use her exhibit to demonstrate the parallels between her children’s picture book art and the visual artwork she does with adults in mind. In late April, the curators will mount a retrospective exhibition of the works of Japanese picture book artist Mitsumasa Anno, including original works from his books Anno’s Alphabet and Anno’s Journey. And before the year’s over, the museum will feature the work of author and illustrator Leo Lionni, creator of Little Blue and Little Yellow, Frederick, and Alexander and the Wind-Up Mouse. The Lionni exhibit should go well with whichever original works by Carle are on display at the time, because the Dutch-born artist uses a similar collage technique in illustration of similarly naturalist themes.

Anyone with children—or anyone who’s spent an hour in a children’s bookstore, even—will know what to expect of Carle’s own contributions to the museum’s exhibition space. His zoologically edifying and endearingly quirky stories are known in daycare centers and brightly colored playrooms around the world. Original works from Eric Carle’s picture books currently on display in the west gallery include the brown bear, red bird, and blue horse from Brown Bear, Brown Bear, What Do You See?, and the ice-blue polar bear, bold blue hippo, and green (with yellow and red spots) boa constrictor from Polar Bear, Polar Bear, What Do You Hear? Trunk and limbs made of five or six orange, brown, and russet painted sections of tissue paper, yellow face, black snout, beady eyes comically true to a kinder, gentler version of reality, the brown bear stares your way. In the book he will answer the question “What do you see?” with his own species-specific response. Similarly, the polar bear and other animals one by one will answer the question “What do you hear?” in reference to creatures presented on the corresponding facing page. “I hear an elephant trumpeting in my ear,” says the boa for example. “I hear a walrus bellowing in my ear,” the pretty tissue-paper peacock with the fanned tail feathers says. Until finally the zookeeper on the last page says, “I hear children…growling like a polar bear, roaring like a lion, snorting like a hippo,” and so on down the line of peaceable beasts from the zoo’s free-range pastures and simulated arctic and tropical environments.

After looking at the Carle collages, you enter the smaller central gallery. The draft pages, story charts, and printer’s proofs of Australian illustrator Robert Ingpen’s 2002 book Halloween Circus at the Graveyard Lawn greet you there. Elegant watercolor and ink illustrations of a graveyard that comes alive on Halloween, these fantasy-land pictures would probably appeal to an audience older than the toddler who’d take easily to the Eric Carle books—maybe even to teenagers familiar with the ubiquitous dungeons and dragons, hobbits and heavy metal heroes, from the escapist popular culture of our day. “Locked doors / owls hoot / bat wings thump,” begins the book, conventionally enough, the large pages crawling with fairies and goblins. It’s interesting to see work so recently finished, but it might have been more interesting (or surprising anyway) to present the original works that went into the making of Ingpen’s more edifying introduction to Shakespeare.

The east gallery of the museum, same size as the west gallery, housed an exhibit of Maurice Sendak’s work through January 12th. It would have been advisable to become intimately familiar with just about everything Sendak ever published—though not so much with his most well-known work, Where the Wild Things Are—before visiting this room. Bits and pieces of many of his books adorned the walls, mixed with original works from such influential old-time children’s lit luminaries as Samuel Palmer, Winslow Homer, and Randolph Caldecott. (Even Albrecht Durer and William Blake made a couple of appearances each in this room, though not with etchings from children’s books.) The drawings formed a testimony to Sendak’s long and varied career in children’s literature. But out of context, you didn’t get enough of the story from one or two pictures to do much more than pique your curiosity about the whole Sendak library. Out of context, you didn’t fully enough understand, unless you already knew the story, the pen-and-ink drawings of a girl named Ida playing the horn in her room, while two goblins stare at her from the top of the ladder that they’ve leaned in the night against her window sill. You wanted to read the whole book to see how that scene corresponds to another great pen-and-ink of Ida brooding under a gnarly tree by a tumbling brook that a group of squat citizens is crossing on a nearby bridge.

The Sendak story about Ida is no doubt for sale in the museum’s bountiful book store, as must be his circa 1950s-and-’60s books Little Bear, Higglety Pigglety Pop!, The Sign on Rosie’s Door, and the more recent Dear Mili (1988)—all of them sampled in the frames of this exhibit. Eric Carle’s books are there—in Spanish, Hebrew, Arabic, and English—and Ingpen’s probably as well. You can expect the rest of the greatest hits of children’s picture books to be there—Alice in Wonderland, Charlotte’s Web, Treasure Island—and you can hope that original drafts of the drawings for such books will appear in the galleries of the Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art sometime in the future.