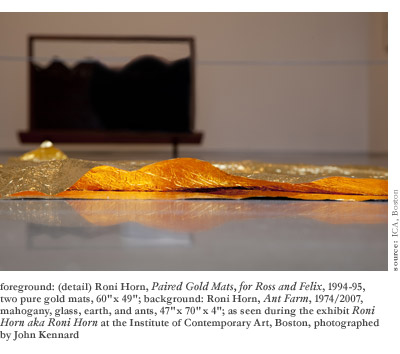

Behind Roni Horn’s sculpture Paired Gold Mats, for Ross and Felix, the artist has made a large rectangular opening in the gallery wall. Where one expects more white flatness, there suddenly looms rippling seawater and, on a clear day, sunbeams streaming through the glazed cantilever of Boston’s Institute of Contemporary Art. As the light dances upon the work—two stacked sheets of gold foil made in homage to Felix Gonzalez-Torres and his lover Ross Laycock after the latter died from AIDS—the precious metal glows and shimmers. That first glimpse of gold against the Boston harbor marks the climax of the exhibit Roni Horn aka Roni Horn, the moment you witness the artist’s work, which so often alludes to the flux of weather, dramatically engage with that flux.

Hosted previously by the Tate Modern and the Whitney Museum of American Art, this is the largest survey to date of the internationally renowned American Post-Minimalist. Exhibited in a reduced format at the ICA through June 13th (since February), it includes over fifty works selected from the artist’s thirty-plus year career. Horn, who was born in 1955, obtained her MFA in sculpture at Yale University and now divides her time between Manhattan and Iceland. Since the mid-seventies, the latter island—with its volcanic geology, capricious climate, and geothermal liveliness—has proved a wellspring of inspiration for her work, which focuses on the unstable, volatile nature of perception and identity.

Iceland’s weather—indeed, weather in general—serves two purposes for Horn. Conceptually speaking, it symbolizes shift, flow, and mutability. Visually, it engages with her reflective and translucent materials to enact such flux. It is at once a thought-provoking metaphor and an awe-inspiring phenomenon. The experience of watching the sun glimmer off Paired Gold Mats, for example, oscillates between a meditation on impermanence and a soothing absorption in the golden beauty. Horn may as well have added “sunlight” to the materials list right alongside “two pure gold mats.” The work does not merely interact with the weather, but, at least in part, literally is the weather.

This peculiarity feels natural within Horn’s weather-centered way of thinking. Her 1995 work You are the Weather consists of one hundred photographs of the face of a woman bathing in an Icelandic hot spring. At first glance, all that seems to change is the rising steam, but a closer look reveals nearly imperceptible shifts in the woman’s expression. Looking closer is a prerequisite for viewing Horn’s work, which is invariably more than it appears. You are the Weather suggests that the same quality abides in the viewer: moment to moment, you appear unchanged, but your body, thoughts, and emotions are always in subtle flux; they are as mercurial as weather. Horn’s title thus reinforces the metaphor of weather as mutability. And yet, since the photographs reconfigure identity as a false construct of sameness imposed upon a volatile cloud of differences, You are the Weather may also be taken literally—you, the woman, and the weather ultimately belong to the same protean continuum of existence.

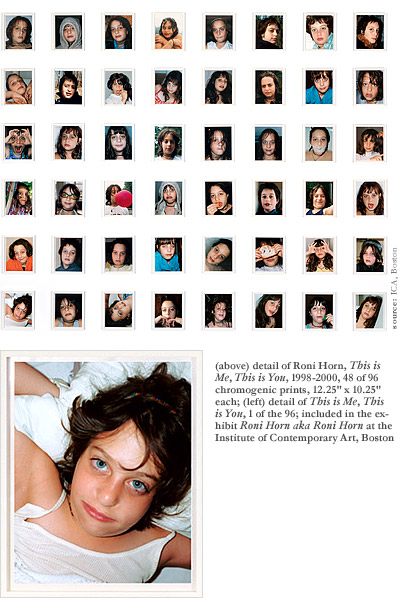

This underlying concern with sameness and difference—a thread running through much of Roni Horn’s artwork—echoes the pre-Socratic problem of the one and the many. And like much philosophy of that period, it seems at times rudimentary, at others elemental and wondrous. The photographic series a.k.a. and This is Me, This is You fall into the first category. The former consists of paired shots of Horn at different stages of life, while the latter presents two nearly identical sets of close-ups of her niece (a dead ringer and stand-in for Horn as a child) on opposite walls. Horn often uses juxtaposition and pairing to invite a second look and to introduce the sameness/difference dialectic. These photographic works meditate on the multiplicity of identities assumed in the course of a single life as well as the impossibility of capturing the ever-evolving self through portraiture. Unfortunately, there’s nothing new here for anyone who has perused old family photo albums and thought, “Is that really me?” Perhaps the same critique could be levied against You are the Weather, but in that work, the woman’s transfixing gaze and the invocation of the elements triggers a response of greater depth. Define, if possible, the essence of your identity, the faces challenge.

Opposite of White, v.1 (Large) and Opposite of White, v.2 (Large), a pair of enormous cast glass sculptures, present an equally robust investigation of sameness and difference. Both are squat and cylindrical with concave, fire-polished tops. The former is transparent and colorless while the latter is a rich onyx with grayish-white edges. The clear cylinder is unremarkable—you gaze into the mass and see everything immediately: a few bubbles that emerged during casting, and nothing else but clear volume. Meanwhile, the black cylinder seduces you with its lustrous polish. You can see nothing of the interior, but so pure is the blackness that gazing at it feels like staring into the cosmos. It summons, as James Turrell has said of his own work, “the wordless thought that comes from looking in a fire.” The cylinders contrast the acquisition of ordinary sensory knowledge (v.1) with that of spiritual insight (v.2) and also address the perception of light, volume, and material. The titles imply that sculpture, as compared with painting, can form white’s opposite in two ways: since white reflects all colors, its opposite can either absorb the colors (black) or permit their passage (clear)—and clarity is a property of materials, not pigments. The abundant visual intelligence of this work positions it at a far cry from photo album uncanniness.

In other works, Horn continues to take up material variance—particularly in glass—to execute some clever art-historical tweaks. She infuses the rectangular prism, a favorite Minimalist form, with vibrant color and personality in a rejection of Minimalism’s cold, impeccably fabricated objects. Untitled (Aretha), a bright red, cast-glass cuboid, teems with the energy of its namesake. Pink Tons, a four-foot cube of pink glass, is a take-off on Tony Smith’s Die, a six-foot cube of stainless steel. While Die is an impersonal, perfect Platonic solid, Pink Tons is rife with cracks, distortions, and bubbles that breathe with a fragile beauty.

Horn is as interested in words as she is in conjuring up a “wordless thought.” Her White Dickinson series consists of Emily Dickinson excerpts cast in white plastic and embedded in aluminum bars. As physical objects, the bars are extraordinary to behold, and the precise method of their manufacture befuddles all but seasoned industrial fabricators. Horn orients them vertically, propping them against the gallery walls in a subtle underscoring of their weight and volume. This concretization of poetic language reminds us that the roots of linguistic meaning lie in physical and corporeal metaphor. “Degrees,” for instance, one of the plastic excerpted words, traces back to the Latin gradus, meaning a literal “step.” As for the aluminum encasing the words, it fills the silent, empty space between the letters, reifying the pre-linguistic realm of thought and feeling that language can only imperfectly translate.

Among the exhibition’s many appearances of language, the most innovative appears in Still Water (The River Thames, for Example), fifteen close-up photographs of London’s evocative river. Water, like weather, symbolizes flux for Horn, and the work encourages our awareness of countless changes in the Thames’ flow from one split-second to the next. At the bottom of each photograph, copious footnotes record her idiosyncratic responses to precise points on the water’s surface. The annotation of something so non-textual is startling. It’s as if we’ve witnessed Horn’s invention of a new academic discipline of aqueous micro-attention studies.

While Roni Horn’s glowing gold and glass provide real-time encounters with flux, Still Water and many of her other photographs address the subtle mechanisms of perception used to process this flux. As such, the latter necessarily lack a strong visual presence. Rather than offering something to see, they condition us to scrutinize how we see. Visitors who find the austerity disappointing will be rewarded upon leaving the ICA. Time spent immersed in Horn’s vision tends to temporarily alter one’s perspective, alchemizing everyday phenomena into art. The harbor’s undulations, no doubt, will appear subtly miraculous, and even more mundane sights—the sun’s reflection in a puddle, a pair of parking meters—will suddenly loom as objects of new curiosity. If one could sustain this aftereffect in a continual life practice, the only conceivable downside would be a disincentive to see more of Horn’s work. As with medicine, the highest conceivable achievement of her art would be to render itself superfluous.