If you moved from Oregon—an active tectonic region ruled by volcanoes and constant, crushing surf—to the tamed landscapes of New England, you might want to recreate the excitement of that primal environment. This may be the impetus behind Patrick Pierce’s peculiar aesthetic, which drives him to populate his home and studio with gawky, hulking, teratological sculptures.

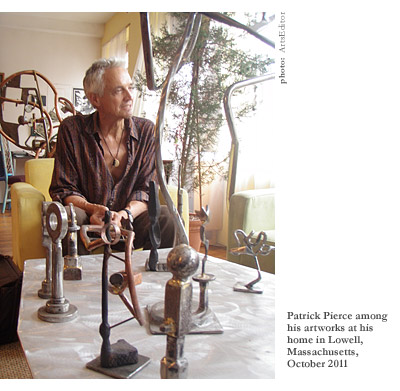

After a half-century of economic decline, Lowell, Massachusetts has become a locus for artists. One of the genuine birthplaces of the Industrial Revolution, and now home to a national historical park of racketing water-powered textile mills, Pierce owns a two-story loft building in the city. He sculpts, paints, writes poetry, lives there, and has populated it with dozens of sculptures and painted objects from his past thirty-plus years. He built the dramatic furniture and light fixtures in the living spaces out of salvage and scrap, a process recently (and correctly only in the case of such furniture) termed “upcycling.”

Upcycling implies an improvement in the status of the objects created from discarded commodities, where recycling often diminishes quality: ground-up substances do not consider the morality or aesthetics of the final product. Pierce has appropriated the term “upcycled” as the descriptor of choice for his work, in lieu of the canonical labels collage, found object, Merz, junk, assemblage, and so on. A web search of upcycled artworks will not reward the seeker with anything of more worth than a recent New York exhibit of art made with used subway cards. The norm for these works is to manipulate various forms of litter to create not the triumphs of abstraction for which we revere Picasso, Schwitters, or Duchamp, but mundane landscapes or banal portraits of rock stars and other celebrities. Upcycled art is bad company whose production—with rare exception—veers toward the corny, kitschy, or cute. Pierce’s re-positioning is a regrettable whim, owed not so much to a reading of the current early-century cultural landscape as to his poet’s attraction to new vocabulary.

Pierce’s recent sculptures are on display in his first floor storefront gallery. Behind a partition, visitors negotiate a long walk between large sculptures to a studio where he welds and bonds industrial materials to organic refuse. On both floors, the environment is populated by idiosyncratic creations that have been exhibited at Denise Bibro Fine Art in New York City, Jessica Hagen Fine Art and Design in Newport, Rhode Island, and many other galleries and public installations.

Since the 1980s, Pierce has produced a substantial, recognizable body of work, developing a mature and personal sensitivity to the material nature of physical things. His work arises from the period and art theory of Abstract Expressionism, and in a way it is reassuring to see that the epoch’s classic vocabulary is still alive in his work—even in the self-effacing nod Pierce makes towards Mark di Suvero by signing his sculptures “Patrik” in the spirit of di Suvero’s unpretentious “Mark.”

Pierce is essentially a practitioner of assemblage, a fundamentally poetic creative mode in which selected objects transcend representation to become parts of artworks. In the best examples, the visual power of each well-chosen, well-arranged object protects the whole from succumbing to visual doggerel, while the objects collectively synergize to invoke an original form.

Pierce delights in the histories revealed by detritus—industrial scraps that have outlasted their purpose—and his finest works contribute to a corpus of junk sculptures and collages that are among the 20th Century’s most original achievements. Despite its central position in art history, assemblage is among the most difficult of styles for the casual viewer to unpack. Pierce’s sculptures are no exception, demanding that viewers make aesthetic sense out of objects whose forms are shaped by their ugly past, surrendering to the beauty of corroded contours and battered surfaces.

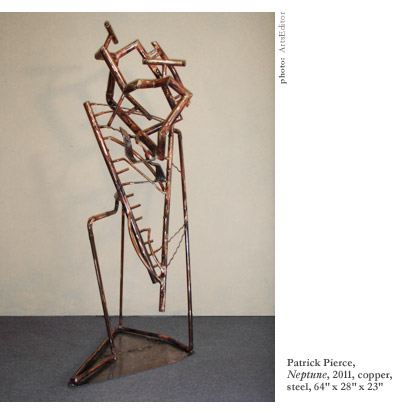

Wrought from copper swimming pool pipes, Neptune rises from a triangular steel base like bony legs, the copper organizing into a kind of skeletal torso with a heavy, outlined, bearded head, like a polygonal line drawing floating in space. The work invokes African tribal deities, or the skeleton of an enormous frog—another amphibious nod to Neptune. Except for a single gawky swirl of steel at the hips, it pursues a strict grammar of lines and angles, a formal virtue that is rarely a primary goal in Pierce’s work.

Largely a slab cut thick from an elm that grew three concrescent trunks, Auricle is mounted on three converging iron rods bonded to a triple I-beam base. The biomorphic structure plays with a pedestal-object relationship, or flirtingly suggests a trunk and legs. The heroically-scaled slab, surrounded by its protective bark, has an undeniably heart-shaped outline, yet it quickly morphs into the head of some great beast, an alien continent, a Stone Age goddess entrapped by a stalagmite, or an archer’s target twisting violently out of harm’s way. It’s a tree grown into a singular form, shaped by climatic history and environmental happenstance. Cut down, Pierce selected this section to preserve and enhance. He responds to its form and history, offering interpretation by carving in relief. Pierce channels his awareness of the tree’s reified energy—a decades-long record of flux—by hollowing out a slit, enhancing a crack, accentuating the complex system of radial ripples that chart a living thing’s developmental course. This treatment is a kind of geographic portraiture that discovers and accentuates the subject’s expressive identity, embracing its natural origin and making it integral to the visual structure. Notwithstanding, Pierce’s selection of accents is confusing, often seeming more decorative than historical or narrative, and while the work is elegantly finished and pleasing to absorb, at their worst the small flourishes suggest a careless and thoughtless origin. Perhaps the underlying message is that the tree grew by chance, and had the good luck to find itself in Pierce’s studio.

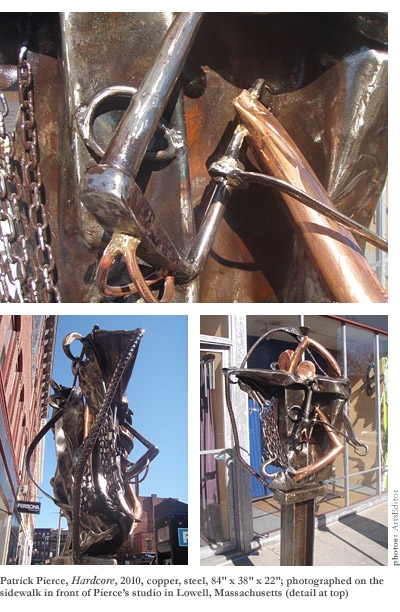

A solid-form parallel to Neptune‘s linear exploration, Hardcore is built from a half-crushed industrial steel tub raised onto a vertical I-beam and fitted together with metallic detritus—heavy chain, a steel hook, copper pipe, rebar, an eye-ring. Neptune’s Greek counterpart Poseidon is often associated with a bull, representative of his geological powers as the god of earthquakes in a temblor-prone region. Prior to domestication in the late Stone Age, wild bulls roamed freely throughout Eurasia, and the awe they inspired is captured in cave paintings, house shrines, altars, rituals, Ionic capitals, and sculpture. Perhaps a half-bull itself, Hardcore recalls the mythical beast, channeling Picasso’s haunting Minotaur series.

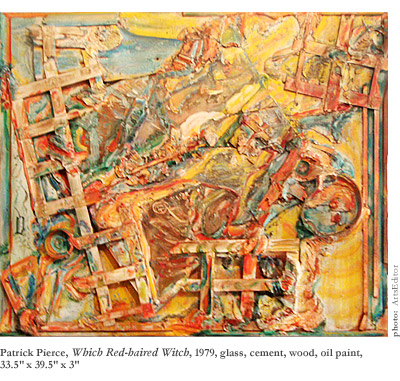

As with his metal works, Pierce’s paintings incorporate the objects that inspire them, typically embedded within a palette of faded indigo and ochre. While his sculptures appear as unique objects first and composite sculptures second, his paintings feel more immediately deliberate and formal in their composition. Combines more than assemblages, they engage the flat, rectangular format even as they project forward and radiate out along the plane of the wall. They invoke Tanguy or Miró’s surrealist dreamscapes and de Kooning’s anxious surfaces, and in so far as Pierce obviously admires Ernst’s humor, he exalts Rauschenberg’s entire oeuvre, declaring it “an encyclopedia.” Distant cousins of Giacometti portraits, Pierce’s images acquire a sense of individuality in visually splintered forms that are firmly entrenched within the traditions of Surrealism, automatic writing, and gesture painting, working to elevate a physical art act as the consummate emotion.

Pierce’s paintings stretch sideways, and often include circular motifs or chunks of grids. Compressed into a shallow surface and bounded within a few square yards, the paintings carry cohesive formal statements more easily than the sprawling sculptures. There, Patrick Pierce is prone to an exuberant lack of control over his creative energy, which overburdens many pieces with distracting and unnecessary ornamentation. By contrast, his paintings rarely betray unworked spaces and their patchy, pastel-hued planes provide a calming, neutral ground, as though the underlying white wall is another constituent part. Their gentle, floating forms counter sculptures that rear up emphatically like self-assembling creatures emerging from a swamp—unbridled expressions of deep, natural impulses, and a stark contrast to the civilized, grammatical wall pieces.

At a certain point, all great artists become autodidacts, but the formal study of art—or at least, colloquy in a community of artists—can save substantial time and error. For forty years American artists flourished in one square mile of Manhattan, until university jobs and rent increases scattered them across the continent. Interestingly though, that proximity is being restored in part by the Internet—even as artists repopulate small, distant cities in search of affordable work spaces. Talent and sensitivity are essential, but conversation among artists has evolved to provide an essential supplementary sensibility that preserves the quality and virtue of their works far into the future. Without this asset, Pierce often seems stricken by an inability to know when to stop working—when a surface has been shaped to satisfaction, or when it is time to leave a suggestive image for the viewer to fill in her own interpretive experience.

Pierce resists the industrial finish of most welded sculpture. He is uninterested in machined surfaces that look as though they have been made by robots, an admirable aesthetic position that merits further exploration—especially considering that it is not always ideally realized. Overlapping reflective circles covering stainless planes are an analogue to chisel marks in stone—at once proof of the human hand and a contemporary cliché. Where other sculptors use a uniformly-mechanistic industrial finish to subordinate details to the whole, Pierce scrawls over his steel finishes with an angle grinder, a kind of automatic writing that furiously scours the surfaces with spark-spinning abrasive discs. Unfortunately, these marks often distract and even detract from the expressive qualities of the sculptures they cover, neither embellishing nor adorning, but rather constituting a sort of historical litter—the tracks of a worker’s footprints on the factory floor. They are mark-making gestures without system or intent, and though they echo certain visual cues key to Abstract Expressionism, they lack form, feel tentative, and are ultimately rendered irrelevant by the final coat of varnish slathered on to unify the composition.

Ultimately, what stands out most about Pierce’s artworks is that they are driven less by static composition than by pictorial flow—a vital investment of dynamic meaning that suggests life, vibrancy, and energy through an all-over aesthetic that keeps the viewer’s gaze in perpetual circuit. The formal appearance of his sculpture is a secondary by-product of the creative act—is it not entirely a coincidence then that he has moved to the city that birthed Jack Kerouac? But Pierce’s jubilant method is also his greatest weakness. Per Richard Stankiewicz—a true father of junk sculpture and a mentor to many artists—”Appearance is never superficial. It is the essence of art.” In other words, an artist’s intentions will not survive unless they are physically realized in his work, and Pierce’s energetic aesthetic often squanders visual power and compositional quality in the pursuit of energy, leaving him with works that are incomplete if not fully vacant.

However, in the face of a large and varied oeuvre, these could perhaps count as minor quibbles. Patrick Pierce’s work is fundamentally original and of compelling quality, and many of the large and most of the small works are elegantly conceived and emotionally mature statements wrought in formally sound visual language. It is just unfortunate that exuberance often undermines the contemplative balance of composition.