I was kind of worried when my friend in Northampton agreed that he and his sweetie, visiting from Maine, would like to see a piece of conceptual art by Norman Rockwell’s eldest son, on display until October at the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art (MASS MoCA) in North Adams. My own amour and I had had a difference of aesthetic opinion with those two on a double date a year or two before. Coincidentally, our brief bicker had been over the contrast between another father-son pair of New England artists—a couple of painters by the name of Wyeth. At the Farnsworth Art Museum in Rockland, Maine, they had adored the magazine and storybook illustrations of N.C. Wyeth for their technical perfection as much as for the innocent iconography of their narratives—cowboy and Indian; pirate and pioneer; Robinson Crusoe and Robin Hood. Dismissing our preference for “bleak is beautiful” realism, they hadn’t even wanted to go to the building next door to see the unmade beds, imperfect nudes, and lonely meadows painted in somber watercolors and temperas by N.C.’s son Andrew.

The similarity is obvious between N.C. Wyeth’s circa-1920s depictions of legendary fictional characters and Norman Rockwell’s post-War illustrations of wholesome nuclear families and sentimental small-town citizens who still seem to have a sense of community: It’s their unmistakable (and in some ways tyrannical) American cheerfulness—a rosy-cheeked optimism conveyed with a draftsman’s precision and an ad man’s imagination. Wyeth and Rockwell didn’t just promote popular culture. Drawing for the popular print media before TV monopolized our free time, they helped to create popular culture.

The similarities of medium, tone, and content are not so obvious between the sons of Wyeth and Rockwell. Andrew, with his precise, detailed studies of logs and nudes, diverged only by degree and shade from his father’s style. Somewhere along the line, however, Jarvis Rockwell strayed far from his own father’s influence. Maybe he took after his dad at first, portraying flag-waving Reaganoids against a blue-sky background or something. I haven’t followed his career. But it’s clear that now, in his 70s, he’s into three-dimensional installations that make good healthy fun of the pre-packaged lifestyles his father portrayed.

Before we made our way to Maya, Jarvis Rockwell’s hysterical homage to pop culture icons, the three of us—absent my companion—had an agreeable time for more than an hour. We were prepared for anything. We’d walked around MASS MoCA’s sprawling complex—the former home, consecutively, of the Arnold Print Works textile company (1860-1942) and the Sprague Electric Company (1942-1985)—pleased that the maze of brick outbuildings and courtyards provided safe haven from the practical world outside the gate.

Our collective mirth had been stirred within a minute of entering the museum. (“You usually don’t see so many people smiling in an art museum,” said my friend to his smiling amour soon thereafter.) Not only were the individual, large-scale works playful and challenging; together they seemed to extend the mass-production theme of the former inhabitants. Andy Warhol’s purposely kitschy conceptual influence, exploiting to comic effect what poet Theodore Roethke called “the endless duplication of lives and objects,” found refreshing new interpretation. It was found in the blank, die-cut jigsaw puzzles onto which Christoph Draeger with cold-eyed clarity paint-jetted photos of catastrophes—settlements and structures broken by natural and induced disasters that themselves were in need of being put back together; a paradoxically mechanistic morphing of form and content. It was found in Danny O’s faded but still colorful collection of found basketball, wiffle, soccer, beach, and other plastic balls, and in Robert Wilson’s installation, 14 Stations, which made sacrilegious yet nonetheless spiritual use of the predictable formality of the religious pilgrim’s sympathetic walk toward Calvary. (Was Wilson restless to venture from the assembly line-like conventions of the ritual—another poke at mass-production?)

The chilling conceptual connection, coupled in a warmer corner of the cerebrum with MASS MoCA’s symbolic use of a blue-collar institution to get a wider variety of people interested in “the arts,” had us floating through the spacious galleries. The glimpses of humble North Adams through the tinted factory windows—worker housing painted in pastels, the Hoosic rushing through its cement canal to an appointment with the Connecticut, the profile of massive Mount Greylock backdropping the view—made ordinary life outside of the museum look rife with dreamy possibility.

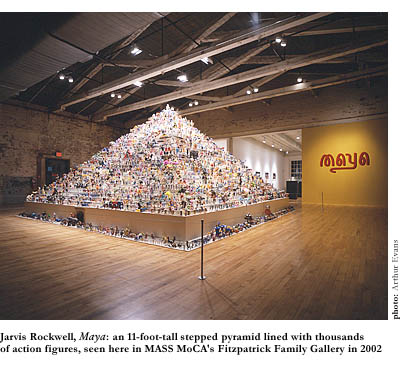

When we climbed the stairs to the third floor gallery, I wasn’t worried any longer that my friends wouldn’t like the wacky work of Jarvis Rockwell. Knowing it consisted of action figures, dolls, toy vehicles, and animal models in lines along the tiers of a tall pyramid, I figured the piece would support the mass-production theme. A press release had explained to me the artist’s interest in Hindu step temples in India; so I knew that the title of the piece referred to the Sanskrit term for illusion. Rockwell, I inferred, would be making the easy point that fantasy distracts attention from the graver facts of life. Perhaps he would be celebrating that on behalf of the children he expected to see the piece. Yet he would be simultaneously showing how the petty amusements of such icons keep us entangled in the world of conflicts and consequences, morals and mishaps, sensations and sins, that the yogis teach us to be detached from—right? The title wouldn’t refer, apparently, to the Mesoamerican people who built their own step-temple pyramids at Chichen Itza, on the Yucatan Peninsula of Mexico.

When we climbed the stairs to the third floor gallery, I wasn’t worried any longer that my friends wouldn’t like the wacky work of Jarvis Rockwell. Knowing it consisted of action figures, dolls, toy vehicles, and animal models in lines along the tiers of a tall pyramid, I figured the piece would support the mass-production theme. A press release had explained to me the artist’s interest in Hindu step temples in India; so I knew that the title of the piece referred to the Sanskrit term for illusion. Rockwell, I inferred, would be making the easy point that fantasy distracts attention from the graver facts of life. Perhaps he would be celebrating that on behalf of the children he expected to see the piece. Yet he would be simultaneously showing how the petty amusements of such icons keep us entangled in the world of conflicts and consequences, morals and mishaps, sensations and sins, that the yogis teach us to be detached from—right? The title wouldn’t refer, apparently, to the Mesoamerican people who built their own step-temple pyramids at Chichen Itza, on the Yucatan Peninsula of Mexico.

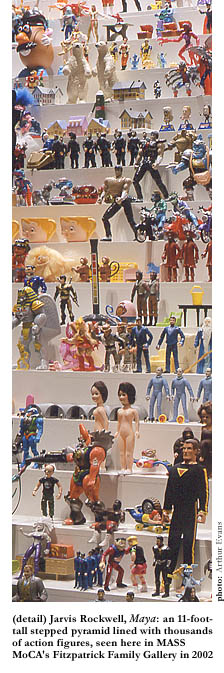

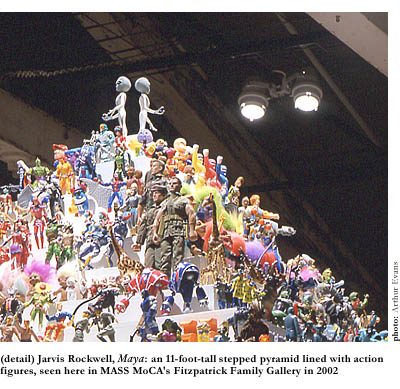

Rather, Maya would do a postmodern Pop Art update, American style, on the traditional pilgrimage of the Hindu worshippers who gaze adoringly at the familiar figures of gods and goddesses carved in the sides of the temple. Manufactured models of Yoda, Mrs. Potato Head, Dennis Rodman, Betty Boop, Howdy Doody, Batman, Simba, Snow White, Homer Simpson, and Duke Ellington in a zoot suit would be standing in for Shiva, Vishnu, Arjuna, Krishna, the milkmaid gopis in their diaphanous gowns, and a thousand other deities from the Mahabharata.

We weren’t the only ones pointing, chortling, and calling out names of our Mattel-, Disney-, Warner Bros.-, and Hollywood-made deities; shaking our heads in admiring disbelief at the egalitarian agglomeration of the deities on the steps of the temple; and taking particular pleasure in the continuous cue of deities entering and exiting the temple’s interior through the one floor-level doorway. A Barbie doll in a two-piece black-and-white bathing suit ahead of a herd of green dragons from some obscure cartoon. A Carl Yastrzemski doll (he did wear the Red Sox #8, didn’t he?), bat over his left shoulder, ahead of a Tonka truck half his size. Some Ninja Turtles or Pokemon monsters mixed into the line with red-haired Annie, wild-eyed Frankenstein, a cuddly wooly mammoth, and a bearded centaur. An equally diverse jumble of figurines up and down the four triangular sides of the pyramid made for a sugar-crazed splash of bright color. Two androgynous gray aliens, said by some museum-goers to be from Close Encounters of the Third Kind, stood watch from the top, possibly in reference to the old belief that aliens built the pyramids.

As elsewhere in the museum—an unusual pleasure to see—the pilgrims were not exclusively iconoclastic artists with advanced degrees. There was a smattering of modest retired couples, people of apparently unglamorous social status—former Sprague employees, I wondered, back to see what strange things have been mass-produced at the old factory since it closed? There were people from the suburbs and small towns—you could just tell. And there were children, lots of children, of all ages with their families.

Among the many excited younger pilgrims at the temple of Americana was Mark Rosenberg, age 5, visiting with the friendly females of his family from a western suburb of Boston. Mark was more than happy to call out the names of all the dolls and action figures he recognized. “There’s Mr. Potato Head!” he said. (“Who?” I asked.) “You know—from Toy Story II!” (“Oh, I’m afraid I missed that one.”) “There’s Buzz and Woody from Toy Story I!”—whatever you say, Mark—”and there’s Sully and Mike from Monsters, Inc.!” Mark even recognized Archie in his Riverdale High letter sweater—or maybe his mother told him who that was—flanked, probably, by some hilarious rubber hippo and a regimented row of clone-like toy soldiers. The mix of storybook, comic book, and Saturday morning cartoon figures with doll-models of heroes from real-life—athletes, musicians, and actors of the entertainment realm—made it hard to distinguish between the actual and the fictional (if there’s any significant difference) and made it ever more apparent that this was exactly the point.

Orange-shirted and eager, Mark probably wasn’t too hip to Jarvis Rockwell’s flip, Warholian commentary on the commercial exploitation of celebrity. (If dolls of Jackie O and Chairman Mao were on the steps with Campbell’s soup cans, I’m afraid I didn’t see them.) He couldn’t possibly have understood the nearby docent’s comment about the bizarre dioramas in the next room, featuring surreal sitting-room situations, with monsters at domestic dinner tables, disembodied heads on upright chairs, and, in one, a wild orange-haired Smurf—at least I was told he was a Smurf—being dressed down for his naughty behavior by the strait-laced, uptight, but completely naked parent figures on either side of him. “Consider how different Jarvis Rockwell’s take on domestic tranquility is from his father’s,” noted the nearby docent.

Maybe Mark will get the culturally complicated jokes behind conceptual art later. If the ingenious and iconoclastic subverts behind the scenes at MASS MoCA have any say in the matter, he will.