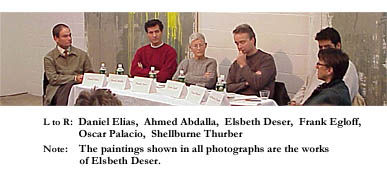

“Boston artist” – a term we hear often. It shows its face at gallery openings, in newspaper reviews, and in everyday conversation. An October 23rd discussion at Elias Fine Art officially titled “Is there Geography in the Art World?” sought to explore questions surrounding the role that geographic region plays in an artist’s work. The discussion, a part of the Boston Art Dealers Association’s Gallery Talk Month, included comments from a panel of five artists of varying backgrounds. The talk was successful in addressing some of the basic issues related to regional influences in art, although it became a bit misguided in subject matter as time passed.

The opening questions posed by moderator Daniel Elias initiated the event. What does geography mean? Can an artist be defined as a Boston artist or just an artist of his or her own right – and of the world? What effect does it have on the content of work? What are the implications for collectors and dealers? How can the positive effects be brought into an artist’s work while simultaneously keeping the negative results at bay?

“It’s really interesting that nobody defines New York artists as New York artists. They’re artists,” noted Shellburne Thurber, a photographer and clearly the most vocal of the panelists. “For a long time I was urged to go to New York. But my work has everything in the world to do with the fact that I grew up around here, I live around here, and my family’s around here. My work is all about home. To move to a place that I didn’t come from doesn’t make any sense.”

Frank Egloff, another panelist who has in recent years exhibited at Elias and the Mario Diacono Gallery, agreed, “There’s been a nationalizing of the art world over the last ten years, which creates an illusion that everything is happening everywhere. But the reality is that is if you think of a place – that figures heavily into the art that’s made.”

An audience member fervently disputed the idea of regional differences, however, claiming that mass communication has created a universal world of contemporary art. “Today, you know what people are doing all over the world. If you go back a little, then geography was important. If you go to an area around Santa Fe, for instance, where you have these little pueblos, you can identify art from every particular pueblo even though they’re just a few miles apart. Here, we’ve been exposed to the universal culture. It’s a much broader experience.”

The question arose about what Boston offers an artist. Does this city function in a different way than other locations?

Ahmed Abdalla is an artist who grew up in Egypt, and whose perspective evolved when he began traveling, leaving his homeland and eventually arriving in Boston. He described the atmosphere of the art scene in Egypt, “The whole art community is very much focused on history. It is also in conflict with contemporary art in Europe and the United States. We were always curious to know what was happening in those areas. See, you are kind of rejected in the art society in Egypt because you are doing something different.” Abdalla’s art was originally centered on such traditional topics as village life, the Nile, and donkeys. And he enjoyed it. When he left Egypt to visit Holland, however, he underwent a crucial transition. “I started to change. There was a need for me to change, to move from what I used to do into something else. It’s not because I wanted to do something that more people can communicate with. It’s something about being. I think location affects very much the artist and his or her work, because there is a different reality.”

Another concern was raised comparing the value of art that is created in Boston to that of other locations. Does the work of Boston have distinct features? Thurber’s immediate position was that academics play an important role. “We are an academic community first and foremost, and a lot of the work that comes out of here is academically driven. I think that academia provides an intellectual ‘featherbed’ for people.” When asked for an example, Thurber related how she viewed a biennial at the Photographic Resource Center a number of years ago. There was an initial “germ of brilliance” in the work, but this germ was overlaid by an enormous number of textual references, revealing an almost “intellectual insecurity” in the work. Thurber explained that she wished the references could have been stripped away and the simplicity exposed.

Several people then voiced the fact that art schools dominate much of the art scene here. An audience member expressed, “The art schools here teach certain students who may not come in with a vision. And sometimes when they come out, they can do a painting or a photograph and it’s barely good. But it has an academic quality and reflects the school or teachers. So I really think breaking away from all of that means truly having your own vision, and making your work.”

That term – “Boston artist” — what does it mean? Is it good or bad? Some people thought it refers to those artists that were born here while others thought artists that work and live here. There was clearly a divide in the interpretation of this ubiquitous phrase.

There was an overall consensus concerning the “Boston artist”, though – that it is not about the style of the work. There is a difference between comparing New York to Egypt and New York to Boston, as another audience member pointed out. Having moved to Boston from New York several years ago, her discovery was that there is no distinction between the aesthetic of two cities. The art is the same.

A second person in the audience supported this. “I was recently talking with a curator whom you all know. He said when he goes to New York to see art, it’s the same as the Boston art that he sees. There’s really no difference in the quality, in the creativity, or in the innovation.”

Indeed, it is the market that draws the difference between the two cities. You typically won’t find confrontational or provocative art here because the market won’t buy it. Elias mentioned that just as the “Boston” tag is used here, New York has its own tag — the “hip” tag. And Thurber agreed, proclaiming that one of the greatest advantages of working in Boston is that there is less pressure to be “hip”.

An obvious question was then posed — why must an artist be categorized and labeled? The general sense was that people require simplicity when digesting the massive amount of artwork available. They need a basic internal categorization system, or a “defense mechanism” as Elias put it. A member of the audience even referred to an artist’s distinguishing mark as a “gimmick” – something that is memorable, that identifies an artist in someone’s mind.

The talk seemed right on target for the first hour, but it unfortunately reverted to light griping about the failings of the art world in Boston during the second. The museum’s responsibility to promote involvement in the arts became a hot topic, and many audience members agreed that our museums need to work together to create a compelling art scene that attracts more involvement. Many potential collectors have felt that the art world has left them out – that it’s too difficult to understand. The museums, press, and city government need to disseminate more information about the contemporary arts. And Boston’s Open Studios have been extremely helpful in bringing the visual arts down to the level of every individual.

It was soon apparent that the subject had steered off course and was not going to be briskly returned from its divergence. The panel became virtually silent even though certain members had not been given enough time to contribute, and Elias seemed unaware of this fact. He consistently voiced his own viewpoint on each topic, although at the outset his intention was to not spend a lot of time talking.

In fact, it wasn’t until Elias’ summary at the closing of the discussion that the topic was brought back on point. “My feeling at the start was that there’s no geography in art. If you’re an artist, you’re involved in an international set of ideas. But my preconception I think is too simple. Geography has many effects on artists’ hope in terms of what they make and how they live and how they are able to produce in a market. Some of those effects are legitimate, some are healthy, and other ones make life harder.”

Well done, though belated.