As Winfred Rembert tells it, he began making his pictures in the early 1990s at the suggestion of his wife Patsy. A man who grew up in the southwestern Georgia town of Cuthbert during the 1950s and ’60s, he used to tell all kinds of stories of his experiences there, yet up in New Haven, Connecticut, where he and Patsy lived with their children, Winfred realized that few others knew stories like his. So, to keep them alive for not just his children but his children’s children, Rembert—a resourceful man, good with his hands, and armed with a certain acumen about how to make tools and machines work for him—chose an extraordinary reserve for the memories of his youth, bringing them to life in hand-worked leather tableaux and colorful shoe-dye illuminations.

An exhibition of the artist’s work, titled Winfred Rembert: Caint to Caint, is on view until March 31st at the newly opened Adelson Galleries Boston, 520 Harrison Avenue in the South End neighborhood, with over three dozen pieces on display. The Rembert catalogues I reviewed before visiting the gallery offered a beautiful overview of the artist’s full range. The bright shoe-dye colors were expertly reproduced; his compositions set in the fields, on the street, at the pool hall, or on the chain gang are electrifying—even on the printed page.

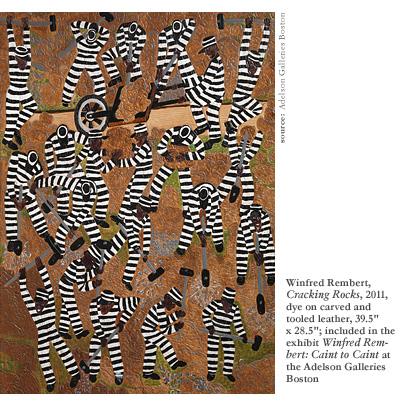

Still, they’re no substitute for standing face-to-face with the works themselves. Rembert’s art may be well represented through framed images on a computer monitor or the printed page, but his media convey a tactile depth, imbuing the images with the physicality of how directly the stories extend from Rembert’s own life. Underscoring this connection, the artist in fact learned leather working while incarcerated in a Georgia state prison, a skillset he would later in life—independently, and with true originality—transform into an art form entirely of his own making.

Rembert’s work is uniquely alluring and arrestingly beautiful. He chooses bright, engaging colors that viewers cannot help but marvel at, wondering perhaps if they’ve even encountered such striking hues before. And yet, undeniably, the same images emit a profound, moving familiarity, whose elusive meaning lies at the heart of why these works are so interesting and powerful.

Two explanations stand out, reflex-like in the mind. The first is Rembert’s skill as a storyteller, which he carries forth from a long oral tradition in his community, where such tales are tied inseparably to the identities of the teller and audience alike. The second is that Winfred Rembert’s stories boldly embrace universal human themes, transcending his community of origin and speaking to the experiences of all viewers from any corner of America.

Put another way, we may not be from Cuthbert, Georgia, yet we understand what Rembert’s stories mean, and perhaps just as importantly, why he’s telling them. Central to this experience, though, and in keeping with the works’ place in a folklore tradition, is co-presence—looking at them close up, breathing the same air they do. To experience the richly-textured leather surfaces, coated with stark-colored dyes, invokes awareness of how both the memories and their representation in these images were made.

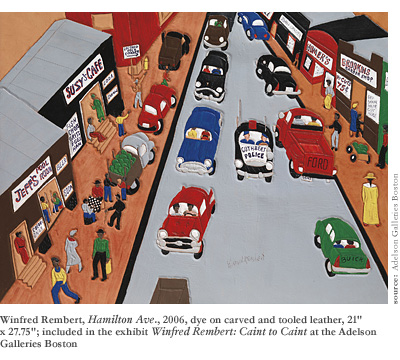

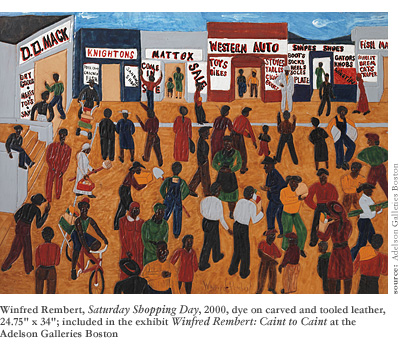

Critical appraisal of Rembert’s style has remained controversial. For example, in the documentary All Me: The Life and Times of Winfred Rembert, a Yale curator wonders whether naïve is the most honest, if undercutting, characterization. (She stands undecided herself.) Fundamentally, this ambiguity may stem from the apparent simplicity of Rembert’s approach to illustration. In Hamilton Ave., he depicts cars and trucks of specific makes—a Ford, a Buick—without motivation beyond their presence in his memories. In Saturday Shopping Day, another of his compelling street scenes, every store bears its name and purpose—sandwich shop, dry goods, meats, toys, boots, socks, heels, wingtips. Whether these inclusions make the works naïve or primitive or childish is entirely beside the point—they are images whose purpose is so primarily tied to storytelling, memory, and personal experience that no statement is being made about brands or commodities beyond “this is how it was.”

Perhaps more to the point, Rembert is hiding nothing in his pieces. Their titles are simple identifiers—Cotton Field #3, The Hungry Eye Café, Pay Off Time—the latter of which depicts just that, a moment of exchange as the cotton pickers’ harvest is weighed and purchased. Although it would be a mistake to confuse Rembert’s simplicity with literal-mindedness, the images are definitely meant to reflect a moment in time, snapped from a specific narrative. To wit, each face belongs to someone Rembert remembers from Cuthbert. Their names come and go among his memories, yet he remembers their roles, faces, and intertwined stories.

Indeed, Rembert often pens a note to accompany each artwork, set it within a narrative arch, and define the provenance of the image in the artist’s expansive memory and experience. The scenes of work and play and even prison life that adorn the gallery walls are an extension of his being and identity, and they convey a stirring sense of who he is. And yet they also capture broader ways of life shared by a community and upheld by a collective spirit that kept them moving through hard and easy times alike, a spirit that perhaps belies the comforting familiarity the works convey to nearly every viewer.

In that sense, Winfred Rembert is carrying on a tradition in the truest sense—he understands how his world works, a sensibility that he translates through his own memories to invoke collective experience. If the documentary film captures the stirring roots of the artist’s life in the segregated South, his trials, and even his surprising good luck, it’s his art that truly reveals the man for who he is, and who he is to all of us, his people.