The morning of Friday, October 4, began as any other day in the life of Stuart X. As usual, he sipped his morning latte while browsing through the business section of The New York Times. Concerned his portfolio had continued its plunge for a third straight day, he fingered his way to the back pages of the stock market charts. A look of dismay suddenly came over him. There, instead of finding numbers, all he saw were miniscule words. Thousands of words. In different languages. Page after page. His immediate reaction was to call his broker. Was this some kind of joke?

A joke? No. An art installation? Yes.

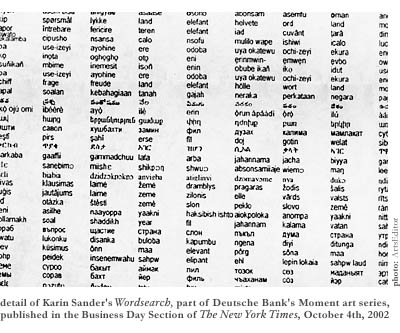

Granted, it’s not your typical art installation, given that it appears in a newspaper. It’s a conceptual sculpture of sorts—or to be more exact, a “translinguistic sculpture” that is three-dimensional in its “crossing” of languages. For proof, look to the banner running atop the eight-page spread, declaring, “Advertisement: Deutsche Bank Art. Karin Sander: Wordsearch, a translinguistic sculpture.”

If this still doesn’t dispel your curiosity, gaze a little longer. Depending on how close one wishes to look, the effect of Wordsearch can vary dramatically. From a few feet away, the gray, miniscule words organized in long columns form an abstract pattern that is strangely beautiful. Arranged to resemble stock market prices, one may easily miss the difference between the two. Up close, Wordsearch may still be difficult to decipher, as there is an overwhelming amount of information on each page, and one isn’t certain how the words, mostly foreign, relate to one another. Again, this reaction is similar to the feeling many viewers get when looking at stock quotes.

Only under intense scrutiny—and the ability to prevent one’s eyes from frenetically jumping around the page—may the puzzle of Wordsearch be solved. At the far right side of every odd page (minus the first page, naturally) is a column of different words, naming languages. The word at the top of the column is English, followed by Fuuta Jalon, Hungarian, French, Arabic, Italian, Yiddish, and so on…ending with Dutch. The astute observer will realize that the confusing words in columns to the left are in fact translations of one another. A thesaurus of languages. Brilliant.

But this realization, satisfying as it is, has only brought to the fore a myriad of other concerns—such as why this “sculpture” appears in a newspaper, and in the business section for that matter. Or why the words resemble share prices. And, most importantly, what does it all signify?

To answer these questions, one must travel to a fateful day a few years back, when the project was first conceived by Karin Sander, a German conceptual artist whose work often employs everyday materials or public spaces. “I was visiting New York and observed all these different languages,” the artist says. “It was incredible and so culturally rich. The question I kept finding myself asking was, ‘Where are you all from?'”

Indeed, in no other city does one hear, in the course of a short subway ride, people speaking Slovak, Dutch, Vietnamese, and Spanish, to name a few. (And that’s not even during rush hour.) Of the 6,800 languages known to exist today (1,000 in written form), many can be heard in New York. The city is undeniably the most culturally diverse city in the U.S., if not the world, and it is also one of the most tolerant. For Sander, New York represented the perfect laboratory to investigate issues of identity—in terms of the individual, groups, and the city as a whole. Language is an essential ingredient in defining one’s identity—tied to it are one’s culture, ethnicity, and family background. In this city of nations, linguistic threads converge and “stretch out all over the world,” says Sander. “Where you come from is an important topic of conversation, and as I lived longer in New York, I experienced that people’s roots to their culture grew stronger with time. I wanted to address these issues of identity in my work, particularly in relation to New York.”

Enter the art custodians at Deutsche Bank, who approached Sander in 2000 about creating a work for their newly formed Moment art series. The mission of the series is to annually present temporary art projects in important cities around the world and to present each for a “moment” in a public space. Created by Deutsche Bank Art as a way to bring a picture, idea, or situation into public consciousness, it also aims to foster tolerance and diversity. The series was inaugurated in 2001 with Shipped Ships by artist Ayse Erkmen, an installation in which three ferries from Japan, Italy, and Turkey were shipped to Frankfurt and run as a ferry service along the German bank and the river.

Eager to put her observations to artistic use, Sander chose the metropolis as her locale and posed the question, “What language does New York speak?” Her aim was to create a lingual portrait of the city by finding as many diverse New Yorkers as possible and asking them to donate a word from their native languages that held cultural significance. Each word, she decided, would then be translated into every one of the other languages gathered in the project, to create what she refers to as a “translinguistic sculpture.” Together, these words would form a momentary story—a portrait in words.

Early on, Sander decided the venue for her “translinguistic sculpture” would be a newspaper—The New York Times. A newspaper, by its very nature, is a temporary, disposable means of relating information and is usually thrown out after one day. It exists for a “moment,” and artists before Sander (Dieter Roth comes to mind) have utilized the newspaper as a medium for its transient qualities. In addition, by presenting a work of art like Wordsearch in a newspaper, Sander challenged its traditional function—which is to convey news and opinions. Undoubtedly, Sander also realized she would be able to reach an audience numbering in the millions through the Times‘ circulation. (On the actual day of the project, the Times was transmitted word-for-word by satellite from New York to Frankfurt, where it was printed, and copies were dispatched in London—which further added to its exposure.)

Early on, Sander decided the venue for her “translinguistic sculpture” would be a newspaper—The New York Times. A newspaper, by its very nature, is a temporary, disposable means of relating information and is usually thrown out after one day. It exists for a “moment,” and artists before Sander (Dieter Roth comes to mind) have utilized the newspaper as a medium for its transient qualities. In addition, by presenting a work of art like Wordsearch in a newspaper, Sander challenged its traditional function—which is to convey news and opinions. Undoubtedly, Sander also realized she would be able to reach an audience numbering in the millions through the Times‘ circulation. (On the actual day of the project, the Times was transmitted word-for-word by satellite from New York to Frankfurt, where it was printed, and copies were dispatched in London—which further added to its exposure.)

By deciding to publish her project in the business section as if it were share prices—in a huge table set in columns—Sander effectively challenged the viewer’s expectations. She demonstrated that art functions in much the same way as a stock market chart. It, too, can be rendered meaningless by people if they are unfamiliar with its code. Further, by presenting words that resemble share prices, Sander contrasted the impersonal numbers that control our economy to the very personal words chosen by its inhabitants. She placed a human value on an otherwise cold form.

Unlike the numbers in the stock market, the words in Wordsearch also follow a principle of equal treatment. Each word has the same status and is given the same treatment, as it is translated into other languages. The placement of Wordsearch in the business section also serves as a reflection on our society and economy and their interrelatedness. We live in a global economy, and without free trade, the free movement of people might not be as acceptable. If this were the case, New York would certainly be a different place. This concept takes on a special significance after the events of last year, when that very freedom was challenged.

From a technical standpoint, the logistics of printing thousands of miniscule words on a limited number of pages clearly pointed to the stock price format, which is an efficient use of space and relatively easy to navigate.

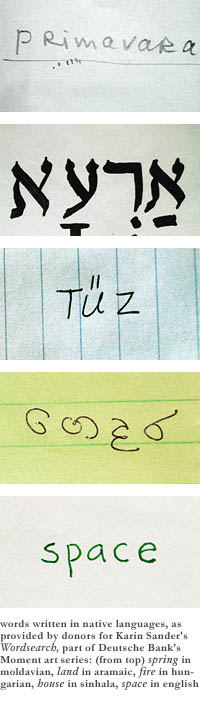

Having figured out the main concept and venue for her project, Sander sent two interviewers on a literal “search” for words in January 2001. In the course of four months, they relentlessly pounded the pavement across the city—into coffee shops, delis, subways, salons, businesses, and parks—in their quest to find diverse New Yorkers who would donate a word that had meaning for them in their culture. Once found, the donor wrote down the word on a piece of paper in his/her own language, and the word was documented visually and acoustically, as well. They ventured into ethic neighborhoods, from Greenpoint, Brooklyn (Polish) to Jackson Heights, Queens (Indian) to Coney Island (Russian) to Harlem (African). Often, an individual would donate a word and then suggest somebody he/she knew who spoke a different language. “It was like a game,” says Sander. “A word chain was created that led through the city and generated its own momentum.”

But it wasn’t always smooth sailing; the word chain would break off whenever the searchers came across a participant that didn’t know anyone who spoke a language that hadn’t already been collected. And, after a while, it was difficult to find any new languages on the streets, so the team began contacting community organizations, religious organizations, educational institutions, and United Nations embassies. Some individuals were adamant in their refusal to donate a word until they had secured permission from their country’s leaders. Others donated words that had already been given. To add to the linguistic confusion, some languages didn’t have a written form, so they had to be left out. And certain African words, for example “menisane” from the dialect Ga, translated into phrases like “what’s the matter” in English—thus providing an interesting challenge for layout.

At the end of a thrilling yet exhaustive four months, Karin Sander and her team had found 250 New Yorkers to donate a word from their native language. Once each word was translated into the 249 other languages, the total number reached an impressive 62,500 words to be printed in the newspaper. Many of the words, which came from familiar languages to the more obscure dialects of Chichewa (of the language Nyanja) and Tagalog (Philippines), tended to be positive signifiers, such as “home,” “welcome,” “love”, “mother,” and “peace.” Others contained an element of humor. (One donor, for instance, was sitting in a bar drinking whiskey when he gave his word, which turned out to be “milk.”) But in general, Sander found a great deal of the words to be based on universal concepts. “The words printed are an image not only of New York but also of those basic concepts shared by everybody living on this earth,” she says. Beneath each word was a story waiting to be told about the person and his culture. The end result, a stunning conglomeration of words, was printed on October 4.

Cultural Mirror is a featured section of ArtsEditor® that includes editorial content developed about the arts outside of Massachusetts, addressing topics in other locations of the United States and the world that may have relevance to our readers.