As anyone who’s looked into Mexican culture knows, the human skeleton is held in high esteem by the Mexican people. A symbol of mortality both more stark and more ripe with comic potential than the black hearse or the white horse, the importance of the skeleton—or calavera—stems from the mixing of the ancient Mesoamerican animist culture and the dramatic Spanish Catholic culture that both saturated and absorbed it after the arrival of Cortés in the early 16th Century. You see the skeleton in Frida Kahlo’s self-portraits and in Diego Rivera’s murals. You see it in altars at Day of the Dead festivities in early November. And I saw it in the pedagogical activities of folk artist Carlomagno Pedro Martinez when he came to town last October from his home in the southern state of Oaxaca to serve as artist-in-residence for a week at the Boston Arts Academy (BAA)—the Boston Public School system’s only arts-focused high school. And then again when he came back to preside at the opening of his solo exhibition in the BAA’s Gordon Gallery in December—which runs through February 15th.

It was no accident of geographical coincidence that led Carlomagno to make the practice of his indigenous ceramic art accessible to teenagers at the BAA, nor that the calavera, the skeleton, was always involved. Art department chair Kathleen Marsh and eight students had met him two summers before on a grant-funded trip to Oaxaca and knew he’d be a good candidate for the cross-cultural residency program at the BAA that has brought several other artists of Latin-American origin to a school whose population is roughly a quarter Hispanic. Visiting visual arts classes that week, Carlomagno worked with an interpreter named Madeline Valera to explain the importance of the calavera, and to show the ropes of skeleton-making to students who’d already gotten their hands dirty in pottery classes.

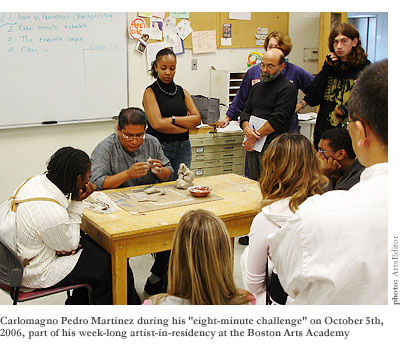

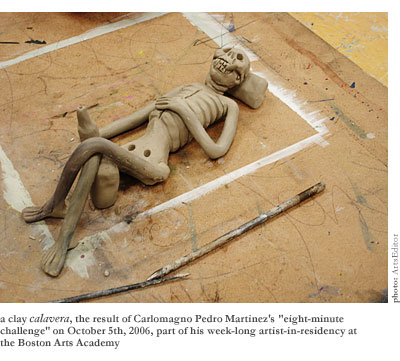

He started by explaining that a typical Day of the Dead tabletop shrine in Mexico includes such somber things as candles, photos, mementos, and religious figures—but that somewhere in the vicinity you’re also liable to find some scary calaveras. Not human-scale skeletons—but toy-sized skeletons like those we might dress in black capes at Halloween and hang from tree branches. Then, without much elaboration, he announced that he would meet his own “eight-minute challenge” to show how quickly he could make a presentable representation of the human skeleton. From one lump of clay on the table before him, he would use a few simple handmade tools to sculpt a small calavera suitable for showing in a Day of the Dead shrine.

The dozen or so students—diversely descending from Mesoamerican, European, African, and Asian ancestries that all have their traditional ways of paying homage to the dead, some more dramatic than others—gathered around the master artist’s work table. The teacher marked the time—8:25 am—and Carlomagno snapped into action.

He didn’t say a word, but the students giggled and chortled, as, methodically and quickly, he tore several wads of clay in rapid succession from the lump. It was the quiet and unassuming manner in which he worked that amused them—and the quiet and unassuming manner that enabled him to roll a few of the wads into balls and a few into bars in under two minutes, in preparation for the formation of the skull, trunk, and limbs of the skeleton. They grinned again when, a little more than a minute later, he shaped one ball into the skull and—in another few seconds—turned a bar of clay into a cloak for the calavera. And they chortled some more when Carlomagno turned those two long loops of clay he rolled out on the table into the arm and leg bones of the skeleton.

Then, as he flattened out a bar and went at it with a metal tool, they hesitated, unsure what he would make. Within another minute they were rejoicing at the sight of the gaunt rib cage of the calavera.

“Cool,” noted one in post-Goth attire, with a very folkloric skull on his t-shirt.

“Awesome,” agreed another.

“Da bomb,” said a third.

Soon, to the delight of the students, there was a clay pillow for the poor bone man to rest his weary head on, and before too long he had a clay cigarette in his jaw and a clay bottle of tequila in his hand, and Carlomagno was saying something like, Mira lo que pasa si se fuma y bebe: that’s what happens to you if you smoke and drink!

The eight minutes were up, and Carlomagno had met his own challenge and earned the respect of the students. The calavera was ready for the shrine. Then he showed pedagogical savvy by presenting a similar challenge to the students, one that would take them through much of the rest of the first period of school. Namely, he asked each table of three or four students to work together to make a different single part of a skeleton—a skull at this table, a rib cage at that, the left leg at another, etc. Ponganlos juntos para ver que producen, or something to that effect, he said: put them together and see what you get!

What you get, in addition to a skeleton with comically disproportionate body parts, is a collective recognition of the mystery of the hereafter, of the sobering mundanity of the human body without the soft miracle of the flesh and its respiratory, circulatory, nervous, and reproductive systems to give it purpose. What you get is an appreciation of the nonchalance with which we live in our sinewy bodies. Our bony, bloody, and sinewy bodies. There’s what we look like deep down inside—”poor bare fork’d animals” like King Lear and his fool, with practical frames for our sensitive flesh.

Ordinarily a bustling attraction to the sort of tourists who seek authentic folk cultures rather than relaxing resorts, Oaxaca, Mexico had been in a state of paralysis when Carlomagno came here for his week-long residency at the BAA. Two months later, when he returned to Boston to install his solo exhibition in the school’s gallery, it was still not back to normal. The perennial teachers’ strike had never ended—and still hasn’t —in a new contract the way it usually does. An intransigent state governor and the election of the right-leaning president Calderon were partly to blame, but so, say some of even the most ardent progressives, was the violent militancy of the strike’s leaders. Yet even as barricades in the state capital of Oaxaca continued to go up in flames and federal troops cracked down on demonstrators this past fall (while a gonzo American journalist caught a deadly bullet in the chest), the mild, munificent, and stubbornly diligent Mexican folk artist attended to his craft.

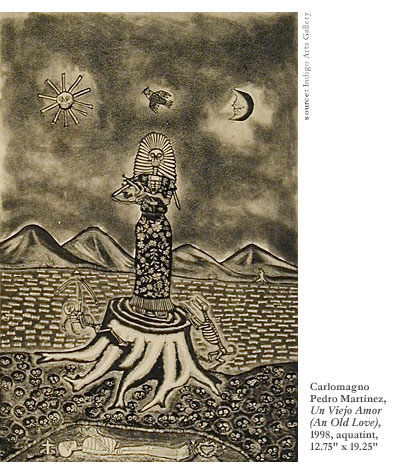

At the gallery on the first floor of the BAA, just over the wall from the bleachers where the Fenway Park creatures boo the enemy right-fielders, Carlomagno held forth to a gathering of teachers and artists. He spoke of his work and its importance to his Zapoteca heritage in Oaxaca. He spoke of the durability and stark charcoal color of his finished pieces—which comes from firing the greasy clay of mountainous Oaxaca in a beehive brick kiln built over a fire pit. He also alluded to the three-millennia tradition of this technique, evidenced as much in relics dug from ruins for display in museums as it is in the cookware still used (and cherished by tourist collectors) in that state. But mostly he spoke of the mythological folkloric symbolism of the often amusing and sometimes serenely affecting small ceramic figures that one person at the opening called a nice mixture of dolor y ternura: pain and tenderness.

There were both pain and tenderness in the numerous depictions of the skeletons of elderly women draped in their rebozos. In one piece, Cinco Abuelitas con Borracho, five skeletal charcoal-skulled grannies sit in stately silence on the ground under their convex charcoal shawls while a skeletal drunk sprawls nearby on the ground, floored by a few too many swigs from the tequila bottle he still holds in his hand. In another, Abuelitos con Murcielagos, a few grandfatherly skeletons sit in the presence of an emblematically charcoal bat. And, in two others, respectively, three old men and three old women sit in friendship, apart from the riling influence of the opposite sex, long after the flesh has fallen away.

There were pain and tenderness in the bizarre depictions of foot-tall calaveras straddling tapete-shrouded corpses of the dead—not to copulate with them or to strangle them, according to Carlomagno, but to give them the final kiss of death. Yet there was also humor in these pieces—as there was, to a much greater degree, in the depictions of La Catarina, all dressed up with nowhere but the grave to go. La Catarina is the Mexican symbol of the lavishly wealthy Europeans who came from France to rule Mexico, if not to re-colonize it, in the 19th Century. By and large a people of modest means, Mexicans take pleasure in poking fun at the pretensions of the prosperous, and these Gallic invaders were the sort of thoroughbred Europeans it’s easy to hate. They were driven out of the country under the leadership of Oaxaca’s favorite native son, Benito Juárez, in the 1860s—with the climactic battle in Puebla giving rise to the proudest patriotic holiday in the country—Cinco de Mayo.

I thought La Catarina was there to teach us some Mexican history, the grannies on the ground to teach me the great Mexican value of familial comfort, and a black clay maize cob on a pedestal to remind me of the enduring staple of Mexico, from ancient times onward. So the familiar signs of Mexican culture prevailed. (I saw some calaveras wearing sombreros and some wearing sarapes.) But after looking at Diego Rivera murals in Mexico, such as the one in Alameda Park that features Rivera himself as a skeleton, somehow I wanted some of the other icons of that country to be on the scene. The conquistador Cortés as a skeleton maybe, with his Spanish armor clanging on his thighbones and La Malinche, his Aztec interpreter and lover, by his side at the foot of a black clay pyramid from Teotihuacán. The Virgin of Guadalupe and her native visionary, Juan Diego, in the pose they struck at the moment of the vision on the hill where the basilica now stands, black clay pilgrim skeletons walking on their knees toward the vision. Maybe Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo themselves to make a threesome of boy-girl pairings—Frida in one of the forms she took in the self-portraits, her body opened like an armoire with rib cage, spine, or pelvic bone exposed.

But Carlomagno is a folk artist—someone who pays homage to the customs of the people—not an urban modernist who makes surrealistic mixtures of registers and images—and paying attention to the nearness of death has been important to Mexicans at least since the Spanish colonization put a murderous, Christianizing end to the Mesoamerican traditions of ritualistic human sacrifice. There’s blood all over everything in Mexico—and there’s a skeleton inside of us all.

The small sampling of Carlomagno’s work at the Boston Arts Academy doesn’t blow you away—it brings you closer to it for a closer look at the meticulous craft work and a sustained grin at the humorous implications of the skeletons, depicted in some of the activities they enjoyed when they still had flesh. You have a little while to see the work at the BAA. But if you want to travel to Oaxaca to see it, you may want to wait until the barricades in the downtown plaza in the capital city have been taken down, the church bells are ringing happily again, and the tag-playing little girls with long black hair are running through the graveyards again, over the bones of their ancestors.