Behind the Sun (Abril Despedaçado) is the latest film from director Walter Salles, whose Central Station received much recognition and won the Golden Globe Award for Best Foreign Language Film in 1999. Behind the Sun is based on the 1981 novel Broken April (Avril Brisé) by Albanian writer Ismaïl Kadaré, but Salles transports the story from 1920s Albania to Brazil in 1910, a region more often associated with the dream-like “magic realism” style of literature (prominent in the work of Latin American authors such as Gabriel Garcia Marquez) as presented in Kadaré’s novel.

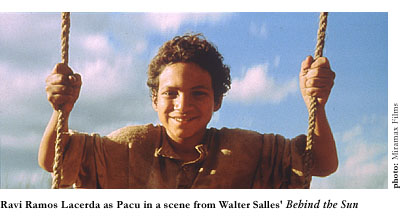

The film revolves around a long-standing blood feud between two families in a small town in the dry Brazilian badlands called Stream-of-Souls. (When at one point a passerby asks, “Where’s the stream?” he receives the answer “Dried up. All that’s left are the souls.”) Originally begun as a land dispute, the rivalry is continued each time a member of one family kills a member of the other in revenge for a previous murder, and is thus an unending and unnecessary cycle of carnage. Our narrator Pacu (Ravi Ramos Lacerda), a precocious boy from the Breves Family, points out that this “eye for an eye” policy can only end in everyone becoming blind. To punctuate this symbolic sightlessness, the patriarch of the rival Ferreira family is in fact without sight, and the stubbornness of the old blind man (Everaldo de Souza Pontes) and Pacu’s father (José Dumont) only serves to perpetuate the bloodshed.

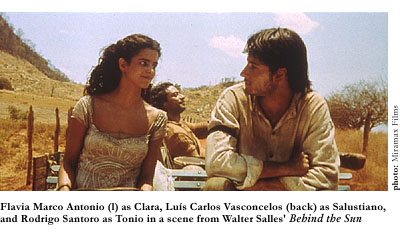

As the story begins, Pacu’s oldest brother Inácio has just been killed, and now it falls upon the twenty-year-old Tonio (Rodrigo Santoro), the next youngest remaining Breves son, to avenge the death of his brother. The ancestral tradition is that the slain man’s bloodied shirt be hung on a line to dry in the sun, and when the bloodstain has yellowed, the next revenge killing can be enacted. The ceaseless flapping of the shirt in the wind becomes a metaphor for the “dirty laundry” of a bloody past that neither family is willing to discard, but the dwindling Breves family, struggling with a failing sugar cane mill, are in danger of extinction at the hands of the wealthier, more prosperous Ferreira family. Tonio is torn between his family duty and his will to survive, for as soon as he acts in revenge, his life will be suddenly divided between the years he has lived out and the scant days that remain before his own time will be up. When a traveling circus passes by, Tonio becomes enraptured with a performer named Clara (introducing the beautiful and talented Flavia Marco Antonio), and escape, encouraged by the young Pacu, becomes even more desirable.

We see the unity of the Breves family through a great deal of the back-breaking labor involved in sugar cane production: harvesting and bundling of stalks, a complex extraction process via an ox-driven press, boiling, cooling, and delivery to a market that continues to cut back both its demand and price in a highly competitive industry. Each family member must help out with the work, including the steadfast mother (Rita Assemany), who has seen so many of her sons die. This literally run-of-the-mill lifestyle is in contrast to the Ferreira estate, which is more sprawling and palatial—they can afford guarded sentries, expensive funerals, and corrective lenses for their brightest son (whose spectacles, ironically, do not help him to “see” any more clearly than the blind old man), but both families are equally unmoving in their resolve and adherence to this gruesome, age-old feud.

Like Montague and Capulet, or like Hatfield and McCoy, the rivalry consumes both families’ everyday life and becomes their identity, to the point where they no longer know any other way. And it is in the traveling circus performers, particularly in Clara, that brothers Tonio and Pacu see the remote possibility of another way of life, one that is as fantastic and as unbounded as their imaginations can provide. For Pacu, this fantasy is contained in a storybook that, although he cannot read, provides him with inspirational pictures of a new, distant world he can visit in his head. But while Pacu has daydreams about his make-believe unreality, Tonio has nightmares about his grim reality. Tonio’s attraction to Clara, despite an unclear relationship with her circus partner Salustiano (Luís Carlos Vasconcelos) and the provocation of the rival family patriarch’s threat that he “will never know true love,” forces him to make a decision about his life, and whether or not he will betray the honor and will of his father and forefathers.

Behind the Sun tells its timeless tale with a true poetic flair. The dialogue, in Portuguese, though sharp, is sparse, and takes a back seat to the compelling visual narrative. The film’s indelible imagery, by turns stark and dazzling, can be attributed to the expert, gorgeous cinematography by Walter Carvalho. Carvalho captures the heart-racing intensity of a chase through the woods with a dizzying effect, and further inventive camerawork captures everything from the freedom of a tree swing—the next closest thing to flying—to the heat of a fire-breathing act. The symbolism is eloquent but simplistic, and never heavy-handed. The bizarre image of the sugar mill oxen circling the press when not being so driven, removed from their proper shackles, gives the impression of the cyclical slaughter that has become a groundless force of habit for both families. In another scene where the Breves family is experiencing a brief moment of joy and harmony, a hard fall from the tree swing brings them abruptly “back to earth”—the same earth that provides their source of income, and the same earth over which the whole conflict between the families began so long ago. The struggle between the earth and expansive blue sky provides many striking images, wherein the characters yearn to break out into the wide open but are bogged down in the mire of their land. Although it is a darkly-played fable, the film is nonetheless awash with sun all the way through to the bitter end, when night and rain fall with the final curtain. The sun, the sky, and the land are counted upon so much in the badlands where there is little else, and we are made to feel that in the evocative camerawork.

The irony of such bitter rivalry over so sweet a crop as sugar cane may account for the bittersweetness in which the film is drenched, and while some critics have taken Salles to task on it—making his film too overly sensual for so simple a topic—there are few films that are able to maintain such a singularly focused ponderousness without becoming boring. Salles’ film is thoroughly engrossing entertainment, and Behind the Sun is one of the more beautiful collections of moving images ever put forth to tell a story.