The most interesting thing I have to say about this exhibition is, well, that I looked good. But we’ll get to that in a minute. Urs Fischer: Marguerite de Ponty is currently on display at the New Museum in New York City, where it will occupy all three floors of the museum’s rotating gallery space through February 7, 2010. The artist has appeared in many seminal group exhibits that took place across the last decade, yet special attention has been drawn to this exhibition—his first large-scale solo presentation in the United States. And it is at best a boring disappointment.

Swiss-born in 1973, Fischer began showing new works in Zurich during the mid-nineties, following the award of several major grants for his promising student work. His early forays into Surrealism were largely unremarkable, but they also exhibited a hungry sense of identity searching as the young artist paused to try on hats of several sizes. As his critical renown grew, Fischer was invited to participate in the group exhibitions that have largely defined his generation of maturing talent on the American art scene—Unmonumental, the New Museum’s 2007 debut in its new SANAA-designed home, the 2006 Whitney Biennial, and the 2007 Venice Biennale.

With each installation, Fischer took up a gestural exploration of violence against the gallery space itself, a technique that has since become both his trademark and a widely-recognized artistic breakthrough. If by the 2006 Whitney Biennial his signature style roared with self-assuredness through full-wall punctures, it was with 2007’s You at Gavin Brown’s enterprise gallery in New York City that Fischer made a truly original statement, by excavating the gallery floors into gaping pits of dirt, concrete, and material detritus. The work was breathtaking to experience and an intelligent reimagining of Allan Kaprow-era installations, presented in juxtaposition with the white walls and fluorescent lighting of contemporary art spaces. Physically, it felt shocking, and the work offered a new and visceral interpretation of sublimity as a function of both human construction and its decay, all while shooting the entire undertaking of art production and consumption an enormous, profane gesture. It was with all this in mind, then, that the announcement of Fischer’s New Museum engagement felt genuinely exciting.

In the press release, curator Massimiliano Gioni declares the exhibition “neither a traditional survey nor a retrospective,” assigning instead the term “introspective,” an expression that suits less for the aptness of presumptive (read: absent) cleverness, but rather for presenting a quick synopsis of why this exhibition is so disappointing—given that Urs Fischer is a relatively young artist, the notion of a retrospective would be presumptuous, and such an exhibit would make poor use of the allotted space. The alternative of an ad hoc State Of The Artist makes for a wonderful promise of mystery, provocation, and psychological exploration, but—like the cheeky-not-in-the-charming-way “introspective” denomination—it proves to be little more than a thoughtless framing of what Fischer has to say for himself, which amounts to embarrassingly little. To this end, the works speak for themselves.

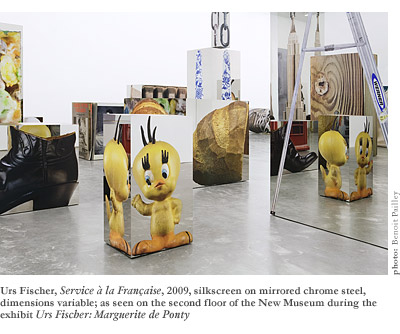

Service à la Française—the exhibition’s centerpiece—lives on the second floor, and it prompts careful consideration. This new work is comprised of 51 large-scale, reflective chrome steel boxes, silkscreened with photographs of everyday objects—a t-bone steak, a lighter, pop star Ashanti, et cetera—blown to super-human proportions. The bricks allude explicitly to Robert Morris’ set of four 3-foot mirror cubes that were placed on the gallery floor. Emotionally, Fischer’s works are gratifying where Morris’ remained elusive—scale alone shifts emphasis from the space to the viewer, which is in keeping with the transformations that have taken place in the collective thinking about art since Minimalism. The mirror surfaces are flawless and delightful to watch oneself in—per above, I looked good—yet where the gestural reinterpretation of the classic work could have emphasized a physical, personal context for interpreting art experience, it is instead sullied by pop-ish hee-hawing. Insofar as the emotional experience of a head-high fruity-loops-treat in breathtaking resolution is indeed quite satisfying, the two visual motifs interrupt one another where the artist may have hoped that they would cohere, and the viewer leaves the space burdened by both unrequited narcissism and a light appetite.

In spite of all this, and in the face of recent critical outcry, I am comfortable praising Fischer for an unapologetic delivery of iconic works. Artists, we are discouraged to remember, must eat and thrive like anyone else, and it is overtly classist to dismiss the need to develop one’s auction value as debase or, in the vernacular, “selling out.” This discriminates against artists fortunate enough to have resources available that let them focus exclusively on new works, and against other young artists who are rebuked for trying to establish a sustainable career foothold in a fickle and chaotic art marketplace. In retrospect, Fischer’s Service à la Français validates You as a masterful maneuver that established the intellectual bona fides necessary to secure the attention of an institution in the New Museum’s league, while positioning the artist to launch a readily identifiable and collectible series. This was a necessary move for an artist so invested in ephemeral, theatrical works, and Fischer’s savvy is absolutely commendable.

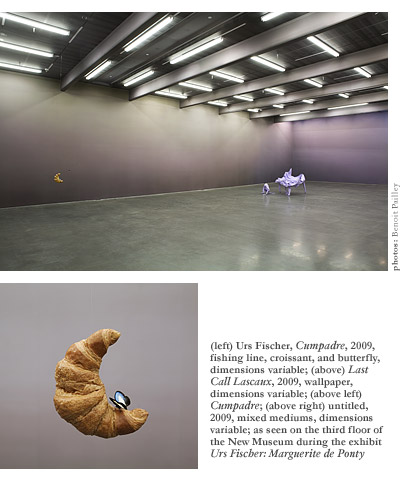

From an academic perspective, Last Call Lascaux is by far the most interesting piece in the exhibit. Fischer photographed each square inch of the third floor’s gallery walls at close range and mounted the prints on top of their respective coordinates. The effect is of a shadowy veil hanging in the middle distance, neither fixable as the wall itself, nor hung upon it. It is a more painterly and less violent addition to Fischer’s gallery-as-piece catalog, and its flowing, velvet hues make an important physical reference to optics, soft perception, and the distance between light-there and light-detectable. If anything, the work would have been elevated by true solitude, and the expansive weightiness of a vacant, off-tone gallery might have constituted an interesting amalgamation of sublime emptiness and Fischer’s characteristically Emperor’s-New-Clothes “Nya-Nya!” Unfortunately, there are distractions.

To wit: the room’s other focal point is an untitled large, distorted, purple piano and an unsubtle reminder that the expectations Fischer’s current artworks meet are those associated with bad Surrealism. The gestures are all readily identifiable—monochrome and melted like a clock, anthropomorphized into a mythical beast—and they transmit archetypal kitsch in lieu of subconscious expression. The same sentiment finds empty resonance in the third floor’s other scant works, Noisette and Cumpadre. The first is a motion-activated tongue projecting and lapping through the gallery wall. The second is a half-moon croissant, dangling from fishing line and perched-upon by an immobilized butterfly. Patronizing mimes of the iconic Surrealist milieu, both works are sculptural equivalents of a platitude, offering things that are neither interesting to look at nor think about. That the introduction to the exhibition explicitly reminds visitors that the butterfly and croissant are constituted from “real” materials makes for an interesting meditation on the distance between the conscious and subconscious articulations of thoughts and abstract artifacts, yet the need for such a note signifies a work without autonomy or the gestalt familiarity of an alien encounter that characterizes surreal experience.

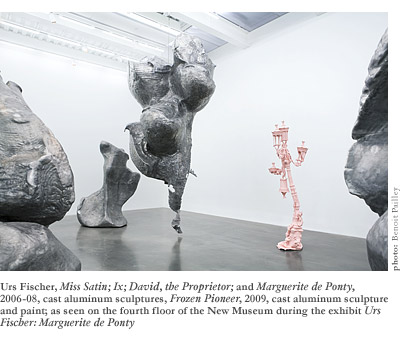

Even more troubling is the exhibition’s pathological mis-organization, generally manifest as incongruous in situ dialog between the artworks. The fourth floor is populated by a coterie of lumpy, oversized metal megaliths blown up from hand-wrought chunks of clay. Aesthetically, each is little more than an inert blob, and their aluminum presence works against what their size and formlessness could have delivered as works erected from the bare remembrances of unsettling dreams. Their sense of scope is well articulated, reaching for Dali’s haunted landscapes or Miro’s colossal, metal shadow-figures, but they also feel severely out of place. Were they implanted like smoke monsters on the third floor’s veiled range, I would happily have foregone both other floors in their entirety. Instead, they take up what feels like leftover space, as they are clustered together with another trite pink melt-piece—this time a lamppost—several wilting blue canes, and half of an excised subway seat, above which floats a disembodied gym bag and its companion cake. Traumatically, these works and the stark blandness of the gallery walls, in contrast with the affected third floor, collectively ground the already too-heavy-feeling dream monuments in a landscape of trite cliché.

Works in conceptual, environmental, and installation media necessarily rely upon Michael Fried’s bedrock the work need only be interesting (“Art and Objecthood”, 1967). Urs Fischer has always seemed well aware of this, and he has regularly delivered compelling acts of subversion, whether by razing a gallery’s floor or punching holes in its walls. His have been brave and uncompromising projects that enunciated in clear tones his creative capacity, fearlessness, and half-antagonistic-half-dependent gunning for arts institutions at large. I would have given that same man my museum to transform, and I would likely have been met with the same display of poor humor, lackluster formalism, and fundamentally uninteresting ideas. There are far better examples of every mood he gestures towards—from earnest Surrealism to naughty playfulness—hanging in the studios of any art school than there are to be found at the New Museum. Ultimately, the exhibition’s greatest value is as a study of anticlimax—disappointment is unequivocally real, and it is with no schadenfreude in mind that we relish an opportunity to observe an accidental and painfully accurate articulation of failure through the pathos of inconsequential art.