The older I get, the more meaningful the story of The Emperor’s New Clothes becomes to me—particularly in the field of art criticism. For so many artists, it seems to me, bear a striking resemblance to Hans Christian Andersen’s swindlers, claiming to have produced a cloak so wonderful that only the cleverest people can see it. And so many critics act like the emperor’s courtiers, too scared of looking stupid to point out to him that there is nothing there at all.

In truth, I struggle to see the point of the courtiers at the best of times. For even when an artist produces a real gown, of wondrous design and exquisite manufacture, why is it not enough simply to enjoy the sight of it in silence? Why try to force it into a linguistic straitjacket—especially one embroidered with adjectives that are, at best, meaningless and, at worst, risibly inappropriate in the context?

Imagine my delight, then, when I received photographer Mona Kuhn’s latest monograph, Evidence—a book in which, for all the multitude of nudes that parade across all but four of its fifty-five images, the emperor is very much fully clothed and the courtiers remain mercifully muted.

Indeed, Gordon Baldwin’s introduction even contains the boon of some solid facts about how the book came to be. It turns out that the photographs were taken in a “rustic community” on the French coast, in which clothes and electricity are largely dispensed with. Kuhn lived with the residents for a number of days in their giant caravans (Thoreau-style log cabins being conspicuous by their absence) in order to build up their trust—although the images are presented as if they charted the course of just one long summer day, beginning with sunrise and ending in candlelight.

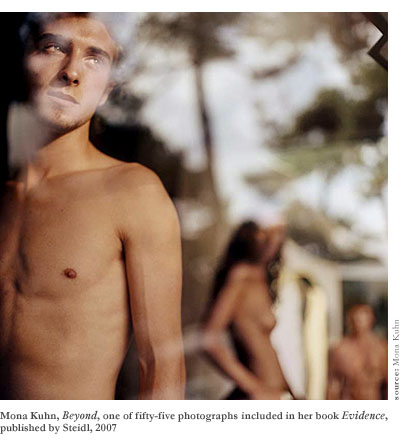

Not that Baldwin is free of the critic’s proclivity towards pretentious nonsense, such as when he inexplicably claims that Kuhn’s models appear to be “nearly entirely beyond corporeal need,” or when he describes her tendency to photograph two or three figures but to focus on (at most) only one of them as “nearly literary in nature.” Yet, for all its being swathed in verbiage, his suggestion that such a technique renders the other, out-of-focus figures a “dream or hallucination” of the protagonist is an interesting one.

Still, I prefer the idea that the protagonist’s thought bubble is inhabited by people who are all too real. For, as Baldwin also acknowledges, Kuhn’s images are drenched with psychological tensions “presumably resulting from their interactions with each other.” He notes that the photographs are “never confrontational” in their level of sexual detail (pubic hair appears in focus only once—and even that obliquely), but also admits that the intensity of the youthful models’ expressions suggests they are “neither naïve nor innocent,” and that sexual undercurrents are unavoidable when people are photographed “unclothed.”

In the end, it is irrelevant whether we choose to see the photographs’ background figures as real, remembered, or imagined. The crucial point is that their relative sharpnesses and directions of gaze are all richly suggestive of jealousy, resentment, exclusion, guilt, and desire. If we were being kind, we could even interpret the occasional pair of shorts or bath towel worn by some of the male models as indicative of some sort of love wound rather than—as I rather fear—an awkwardly coy, aesthetically jarring attempt to preserve the delicate viewer from the sight of an in-focus penis.

Yet for all the loincloths and caravans, despite the standpipe in Bather and the infernal tattoo in Johnny, Kuhn’s images retain a distinctly poetical, before-the-fall feel in their (near) naturalistic purity and the abundant sunlight in which so many of them are bathed—a sunlight that, depending on the hour, can be richly golden, like that of Hopper, or dazzlingly bright, like that of Monet.

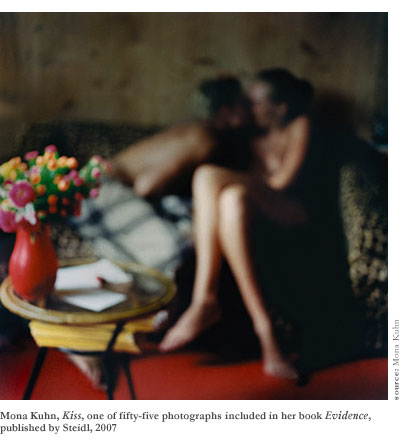

Indeed, Kuhn’s focusing trick frequently renders the background figures mere splashes of colored light, and in a number of images she goes even further, de-focusing the entire image so that the effect comes as close to Impressionism as (unaltered) photographs ever could. (Particularly successful in this regard are An Open Door, Brian by the Tree, Kiss, and especially Three Figures.) Add to that the more classical artistic virtues of careful posing and directing of sight lines and we are left with images every bit as rich as paintings.

Kuhn’s other recurring motif—that of shooting through windows—also lends her images an otherworldly quality through superimposing images of the woods outside onto the figures more or less faintly visible within. I have to say, though, that I don’t appreciate the spell-breaking reflection of the photographer in Closer, even though the fact that her shoulders (the only part of her visible) are apparently naked goes some way to answering the intriguing question of whether part of the trust-building process involved going native herself.

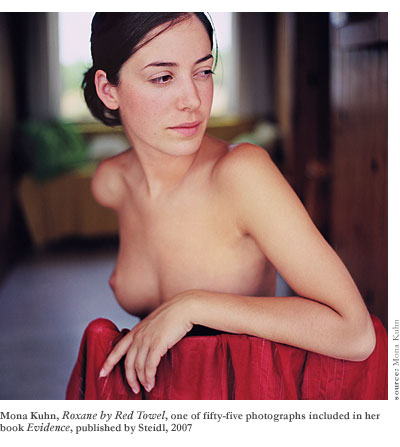

Indeed, such is the prevalence and success of these conceits that some of the straightforward single-person studies, such as Side or Julie, seem deflatingly prosaic and could, perhaps, have been left out. On the other hand, that would also have involved the loss of Roxane by Red Towel, in which the model’s dark eyes and hair are wonderfully set off by the eponymous red towel on the back of her chair.

The single studies in the night section of the book are also resoundingly successful, particularly the adjacent images Orpheus and Papillon, in which the ripe, golden candlelight picks out just enough of the models’ bodies to illuminate the impenetrable darkness with suggestion and meaning.

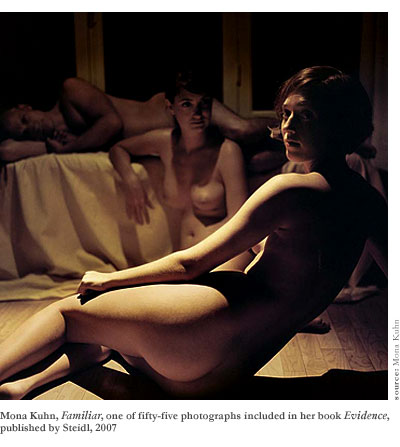

The nighttime photos inevitably represent a somewhat stark shift in tone from the rest of the book, but the fact that they are heralded by a model-less image of the deep orange remains of the sunset glowing on a distant building slightly eases the transition. Meanwhile, the interpersonal tension of the earlier images is maintained, not so much now by focus effects but by the equally intriguing technique of bathing the models in sharply varying levels of candlelight. (See Mermaid and Two Others for a particularly successful example.)

Besides, whatever infelicities of aesthetic continuity it might create, the inclusion of the night photos is more than justified in my eyes by their sheer beauty. The (pseudo) wooden floors and the pale sheets with which Kuhn drapes the caravans’ interiors match the models’ skin tones, rendering the sequence of images a study in pure, unifying gold that reaches its stunning climax in Familiar. That antepenultimate image depicts a strikingly beautiful woman reclined across its foreground, her half-clenched fist and guilty glance at the camera combining with the glare she receives from another woman further back to evoke—perhaps more emphatically than any other image in the collection—a sense of conflict (presumably over the man lying semi-visibly in the background).

It is this emotionally fractious aspect of the photos that Frederic Tuten picks up on in his story, Self Portrait with Beach, which ends the book.

The story concerns a self-confessed voyeur—the narrator—who all but admits to his girlfriend that he will abandon her once her beauty fades. However, that sense of the hard sexual focus with which (some) men view women seems at odds with the more subtle and complex relationships hinted at by Kuhn’s models—their nudity notwithstanding. Nor do the fears of Tuten’s characters about the onset of middle age obviously link them with any of the models in the photos—while the emaciated, grey-bearded man incongruously depicted in Mon Frere seems, by contrast, too old.

But the photographs’ rather magical realism is reflected in the drink that the narrator buys from a beach hawker (a descendent of Andersen’s swindlers, perhaps?) who says it can restore youth. And perhaps the sense that youth and beauty and everything that goes with them must fade is an appropriate ending for a book whose golden summer light is strangely reminiscent of autumn, and whose final image depicts a lone female figure staring into a vast swathe of blackness.

So if I still have a problem with Tuten’s story, it is that it simply isn’t as good as Kuhn’s photos. The clumsiness of such phrases as “the lines had grown even longer, extending far down and along the shore, which had turned a squalid gray, like the gray sky and sea” just don’t measure up to the virtuosity of her camera work. (The sentence has too many sub-clauses and a simile that merely states the obvious, since you ask.)

But I’d still far rather read a story inspired—however imperfectly—by the contents of a monograph than the usual extended essay on the artist’s oeuvre that only succeeds in obscuring her achievement in infuriating thickets of language. Indeed, Mona Kuhn’s own motto for her book, for all its obviousness, seems worth repeating here: “The most immediate form of evidence available to an individual is the observations of that person’s own senses. An observer wishing for evidence that the sky is blue need only look at the sky.”

By the same token—and if you’ll pardon the pun—any observer wanting proof that Kuhn is a wonderful photographer need only feast their senses on Evidence.