There exists a deep connection between initial thoughts in self expression and paper. Looking at handwritten manuscripts or thumbnails can reveal the creative process in ways that other documentation techniques cannot. Paper, a strange composition in itself, consisting of thousands of fibers of almost any material—cotton, wood pulp, reeds—soaked, mashed, and made into one, is a microcosm of the very process it aids. Seemingly disparate elements blended together generate a unified piece. Appropriately, the works in Works on Paper Invitational echo the paper making process, with the diverse subject matter and use of papers assembled at the Nielsen Gallery, which was fortunate to have the co-operation of the Forum Gallery, Robert Miller Gallery and Pace Wildenstein Galleries. An impressive collection of works by regional artists like Anne Harris and art stars like Kiki Smith and Yayoi Kusama line the walls of the converted townhouse that still retains its Brahmin charm with vividly tiled fireplaces, hardwood floors, and bay windows.

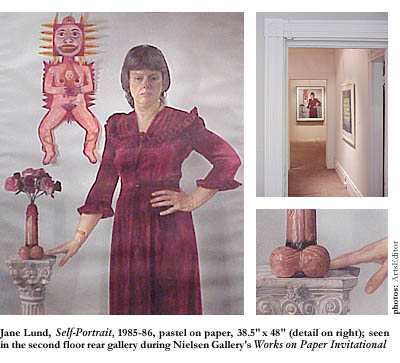

The matriarch of the show hangs in the rear gallery of the second floor, a questionable place for such a powerful piece that instantly demands attention for its size and subject matter. That said, if considered in the context of Louis the XVI, the large pastel occupies the correct salon, which might be considered akin to the royal apartments of Versailles where the sun king received guests. Placements aside, Jane Lund’s Self-Portrait, at 38.5″ x 48″ in pastel, dominates the space with the lovingly rendered tones and notes that resonate with sensual attentions to the slightest details of light. The velvet dress worn by Lund in the portrait evokes thoughts of the decadent richness of curtains found in Caravaggio’s paintings. Speaking compositionally, the elements of the painting are more provocative than the rendering of the colors in the piece. The figure faces full forward and her hand rests lightly on a Corinthian capital with a glowingly glazed red penis flower vase sprouting roses. Yes, the symbolism is a bit overbearing; however, the meat of the work lies in the bizarre totem in the upper left portion of the painting. Upon close inspection, it appears to have been created in magic marker with its flatness and broad strokes (a testimony to the skill of Lund in creating such effects). It is wantonly tacked onto the wall in the image as if almost an afterthought, which contrasts greatly with the reflective mood in the rest of the piece. This idol is a collage of sorts, with human cartoon features melded with a strange mask, an upward pointing arrow with a baby face in the center of it, and a lone hand reaching out of the genital area. Instantly, connections come to light with other works in the exhibit, just as those lone fibers do to create a single sheet of paper.

Looking at the intensity of Jane Lund’s gaze and the potent humor of that juju piece, one can see the fine line between inner voice and accepted reality that some artists attempt to balance upon. Several of the artists represented in this show take that space between those worlds, the space that Roberto Calasso in his book Ka describes as the place between earth and heaven, and dive into its murky depths, pushing their media to give voice to the unspeakable, attempting for a moment to pass the exhilaration of discovery to another with a language that is their own.

Porfirio DiDonna breaks into this in-between space with his untitled piece. The work consists of a series of marks on a framed sheet of 30″ x 22.5″ watercolor paper, the standard size for paper from the local art store. The strokes within the space are thin horizontal rectangles and squares arrayed in a square composition. The trail of the brush traverses the page as a manifestation of visible Morse code in light and dark greens—that if put into song might resemble the circular harmonies of a woodlands pond at dusk filled with peepers and crickets. The patterns are consistent and belie a meditative quality, gently reminding the viewer that although the marks are repetitive, they bear the distinctions of human imperfection with slight differences in line weight, shape, and space between strokes. The work stands on its own as a piece that holds semblance to a personal language, but that like the Lund portrait, still manifests the tensions of the order of linear worlds opposed to interior expressions of time and vision.

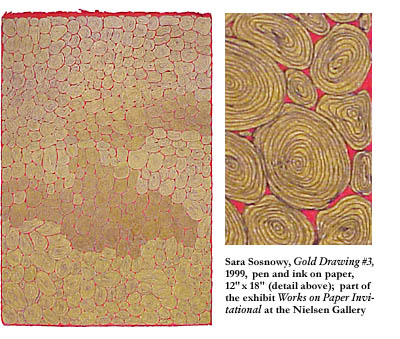

Gold Drawing #3 by Sara Sosnowy contains echoes of this drive and adventure. A smaller piece, 12″ x 18″, it hangs unframed on the wall, its deckled red edge facing the ceiling above, while all other sides are neatly trimmed. The forms speak of obsession; tightly rendered concentric circles reminiscent of cells or fingerprints populate the span of the paper. The materials are simple pen and ink, perhaps the most democratic of any media used in the show. The principal color fields are gold and metallic sienna, with the golden color enveloping the two darker, amorphous forms. The rhythm of Gold Drawing #3 draws the viewer in closer with its hypnotic, redundant labyrinths in the overall pattern and the individual cells. There exists a certain poetry in these self-contained units that accumulates to form a greater composition, sensually retaining autonomy in the midst of a greater whole. These are the connections to language and personal expression that are so compelling in this work.

Like DiDonna’s untitled piece, Gold Drawing #3 exudes a meditative quality that, like the forms in its composition, draws the viewer into the picture space. Sosnowy moves this process one step further from convention by presenting the piece without a frame, mounted on a wall. Nothing separates audience from work. True, presentations like this one are a conservator’s nightmare, but there is a spontaneity to this work that grants it eternities far more lengthy than any museum or corporation could dream of, even if that corporation might move it into cold storage away from the public view beneath the Western Pennsylvania Hills.

Completely pushing the boundaries in this exploration of the space between is Susan Wilmarth-Rabineau. Comet, created with crunched and burned rice paper, charcoal, pastel, and conte crayon, tears through the imagination as a streak of brilliance. Hers is one of the few pieces that goes beyond the “framed convention” and the orderly imposition of marks on paper. There is always a certain amount of order involved with any human endeavor; however, by using fire to burn holes in the work, she lets go of the guiding vision that informed the creation of the work. There is no way that she could have planned exactly how the holes would burn. Following this path might represent the truest exploration of letting the creative process take over and evolve as it is without preconceived notions or ideals. As true as that path might be, though, there shines a beautiful irony in this notion of letting go. Even in the process of relinquishing control, humanity still retains elements of itself in its explorations of the infinite and indescribable.

Comet pleases also on the aesthetic level. It leaps into the gallery space, contained only by the necessity to keep it on the wall. Brass tacks hold it against the grasp of gravity, creating a visceral tension of binding restraints upon a vital object that once had a life of its own. The swirls and marks in the tail of the comet are vibrant and work with the choice of rice paper to breathe added organic vitality into the piece and instill a sensation of motion and emotion that mingles well with the paradox of the media used to create the piece. These materials are the opposite of the elements in a true comet—fire and ice and rock. Such subtle juxtapositions fire up the mind to explore and process these contrary questions and to transcend the dualities to seek connections that will somehow contextualize the viewing experience.

John Lees’ Airstream Hermit (II) presents a shining objective example of an artist involved in the exploration of these dual worlds. Upon seeing this 4″ x 5 11/16″ piece done in ink on paper, one sees the immediacy of the process and the continual attempt to capture the impressions that accumulate like the swirls in Sosnowy’s Gold Drawing #3, the lines in DiDonna’s untitled work, and the burned holes in Wilmarth-Rabineau’s Comet. The swirls of wet ink dried in puddles, the improvised addition of extra paper to the side of the piece, and the frenetic brushstrokes that pay distant homage to Zen master paintings by the likes of Basho, capture parts of those moments that Lees attempts to convey to the viewer. There is a wonderful freshness to the execution of the painting and a vitality in the honesty of the forms that are not overworked or erased or “perfected.” It is a momentary act, and like the other works in the exhibit represents process, internal language, and the meditative states that the artist has tapped to summon his imagery.