On a cold Thursday night in Cambridge, Massachusetts, a man with an acoustic guitar climbs up onto the stage of the legendary Club Passim. The man is joined by a handful of other musicians who, after settling in, and with no introduction, break into a riotous number with a driving beat. Slapping his guitar in alternate punctuation with his sharp strumming, the man leans into the microphone and belts out in a gravelly voice:

I miss you Boom Boom John Lee

I miss you Boom Boom John Lee

I miss you and your beat

And the stomping of your feet

I miss you Boom Boom John Lee

The song, “John Lee,” from Alastair Moock’s 2002 album A Life I Never Had, was written in tribute to groundbreaking folk blues artists like Elizabeth Cotten, Jimmie Rodgers, and others (including the song’s namesake, John Lee Hooker). The lyrics self-referentially bemoan the fact that now that those originators are gone, “All we’ll have is tribute songs.”

Alastair Moock plays acoustic-based songs, but he’s uncomfortable trying to fit into either of the categories that this distinction usually implies—singer-songwriter or folk singer. “Folk music is a term that’s sort of lost all of its meaning,” says Moock over the phone from his home in Iowa, with a slight pause to collect just the right words. “I find ‘Americana’ a more useful term than folk music. There’s something about it that allows you to be referring both to contemporary and traditional music.”

But even the term “Americana” doesn’t quite describe his rootsy approach, which also derives much of its inspiration from the blues and other genres. Bridging those styles of music is central to Moock’s music, but no more so than the act of breathing life into the ghosts of the past. Whether he is singing a song from an earlier generation or one of his own compositions, Moock’s music infuses the spirit of an older age and an institution of songcraft oft forgotten or swept under the rug.

Moock possesses a stirring, emotional voice that’s been likened to Tom Waits but maybe falls more in the realm of a sandpapery Rod McKuen, with the sensitivity of early Dylan and the growl of Steve Earle. The clever wordplay of his lyrics combines frankness with a maturity that belies his years (still in his late twenties). No matter how serious the subject matter of his songs, there’s an underlying humor throughout, particularly onstage, where Moock seasons his performance with wry remarks between tunes. (It’s no wonder, with this untapped comic talent, that Moock counts George Carlin among his fans.) Steeped in tradition, Moock has a deep respect for the acoustic music aesthetic laid out by his folk forbears and those who’ve carried on the flame. He cites among his influences Mississippi John Hurt, Guy Clark, Townes Van Zandt, and John Prine (whose song “Paradise” is covered on A Life I Never Had, with the vocal assistance of Tracy Grammer and the late Dave Carter).

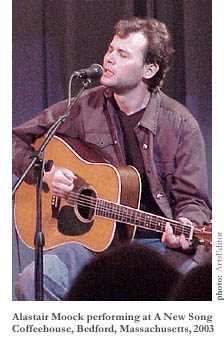

Before his recent relocation to the Midwest, Moock worked the clubs in and around Boston, starting with open mic nights and gradually working his way up through the scene. “I came to Boston kind of randomly after college,” he says. “I didn’t know that much about the contemporary folk scene getting out of school, so I wasn’t really aware that Boston was such a hotbed of songwriters, but it turned out to be a good place to land.”

The strong, established local folk scene presented Moock with the opportunity to cross paths with artists like Ellis Paul, Mark Erelli, and Frank Morey, but at the same time, he found the scene somewhat “clique-y.” Moock recalls, “There didn’t seem to be a whole lot of overlap between the singer-songwriter world and what was the roots community then, which I think has really grown in the last several years in Boston.” To help promote a cross-pollination of creativity between these disparate groups, Moock began a series of collaborative concerts entitled Pastures of Plenty (named after a Woody Guthrie song). “I started Pastures largely…to try to bridge some gaps between different music scenes in Boston, but just as equally motivating was the desire to share the stage with other musicians, and sing other people’s songs.” Moock brought the continuing Pastures of Plenty series to the historic Newport Folk Festival last year, as part of the Roots Stage that coincided with Dylan’s triumphant return to the Rhode Island festival.

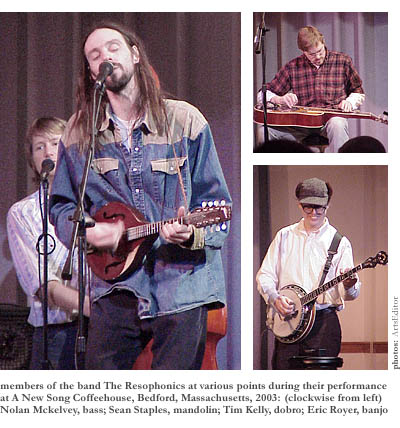

One of the key elements of Pastures of Plenty, and in all of Moock’s recordings to date, is progressive bluegrass group The Resophonics, which Moock refers to as “sort of the house band of Pastures.” Members of The Resophonics can be heard all over Moock’s albums—in particular dobro king Tim Kelly, mandolin master Sean Staples, and expert banjo picker Eric Royer.

Moock currently has three albums under his belt (and enough songs for a fourth already in his head), and the process of compiling a record has become tied to his songwriting. “One of the things that I really like about making an album is the chance to look back over the last 10 or 12 songs or whatever it is you’ve written, and try to figure out what the theme is inside there. It’s one of the really cool things about writing; there’s this whole unconscious thing that happens…I’m often amazed when I look back on my own writing and realize there’s a theme that I wasn’t aware I was writing on.”

For the title of his most recent release, Moock took one of his song titles, “A Life I Never Had.” He explains, “The title is partly addressing the fact that I was doing covers of songs about experiences that are very different from my own…it gave me the freedom to do whatever covers I wanted to do; not have to fit them into a certain category or style.” The aforementioned covers, which include a rendition of Guthrie’s “Pastures of Plenty,” are well-chosen and tastefully performed, but the real gems of A Life I Never Had are Moock’s originals—sometimes reflective, sometimes “in-your-face,” and sometimes both, as in the case of the confrontational beat poetry of “The Word I Said (or the Slut Poem).” That song, which humorously recalls a playground misunderstanding from Moock’s childhood, is appropriately followed by “Put Your Foot in Your Mouth,” which celebrates the honesty of everyday mistakes.

Moock’s songs tend toward extremes, with self-satisfying song titles like “Here’s a Latte and My Middle Finger” at one end, and self-deprecation at the other. For every moment of levity, there is a heavier meditation like “The Bottom of a River,” which offers up an uncommonly vivid take on the classic theme of watery suicide, wherein the narrator imagines the riverbed is “bound to be more soft” than a lost love’s bed. The songs of death, though, sit alongside songs that promote the power of healing, such as “Nothing in this World,” in which Moock’s narrator plays faith healer to a congregation of back-up singers enthralled with his notion that “this song’s gonna cure your ills.” When not preaching the gospel, Moock’s mood ranges from the ramblin’ storytelling of “Never Left the Road Behind” (which has an irresistible “Folsom Prison Blues”-style shuffle) to the more introspective and often poignant, as in “Somewhere Elseward Blown,” when he sings that “even memories get forgot.”

Throughout all his work, Moock’s songwriting follows the standards set down by the originators of the folk and blues forms. “I’ve always been drawn to music that uses structure, and always found it more interesting than the free-form lyric writing found in contemporary singer-songwriters’ work,” Moock explains. “I’ve always liked having a structure you can break away from. If you start with no structure, it’s hard to know what to do [and where to go] with it.”

How personal are Moock’s songs? “You can only write what you know. It’s a rule you can’t get around in music. My goal in songwriting is to try to make what’s personal universal to a certain extent. I try not to do too much navel gazing.” Certainly, turbulent recent world events have diverted Moock’s perspective even further from his belly button. “Lately I’ve been writing a lot more political material than ever before,” he says. “It’s a new experience. I’ve always been drawn to it, and a lot of what drew me to Woody Guthrie, Pete Seeger, John Prine, and a lot of the guys who first made me interested in folk music was their political bent.” Moock has struggled with his past attempts at political writing, which he says have “always come out dry and stale. I wasn’t able to connect the personal and the universal. I think my whole generation is self-conscious about being earnest.” But inspired in part by the spirit and scope of recent protests, Moock feels he’s finally getting comfortable with that side of his songwriting.

That’s not all that inspires Moock, though. “I can’t wait to see A Mighty Wind,” he reveals, referring to the film opening later this month in which director Christopher Guest sets out to parody the folk music revival of the ’60s in the same fashion that This Is Spinal Tap skewered the heavy metal genre 20 years ago. Surely the loving jabs of A Mighty Wind, delivered with a knowing wink, draw on the creators’ fond respect for folk and Americana, similar to the musically rich film O Brother, Where Art Thou?, an invention of the Coen Brothers (of whom Moock is also a fan) that spawned an unprecedented roots music revival all its own. Although the unprecedented popularity of the film’s soundtrack had a positive outcome in that it gave a significant boost to bluegrass and folk performers old and new, Moock refers to the O Brother phenomenon with trepidation. “I don’t know what the long-term effect of that is. I don’t know if it’s just sort of a passing interest that people have, like the thing that happened with swing music a few years ago, where [afterwards] everyone sort of puts it on their shelf.” At the same time the film spurred a roots music boom, it eventually turned into something of a backhanded compliment to the Deep South originators of that sound, with the film’s complicated and multi-layered critiques of stereotypes that, though smartly done, influenced a fad that ultimately cannot help but sit a little funny with Moock. “It reminds me of these stories of Woody Guthrie coming to New York. Somebody wanted to put him in a show at the Rainbow Room where he was all dressed up in a hillbilly outfit with a straw hat singing old dancehall songs for a bunch of wealthy New York sophisticates, and [Woody] just walked out on it.”

That’s not all that inspires Moock, though. “I can’t wait to see A Mighty Wind,” he reveals, referring to the film opening later this month in which director Christopher Guest sets out to parody the folk music revival of the ’60s in the same fashion that This Is Spinal Tap skewered the heavy metal genre 20 years ago. Surely the loving jabs of A Mighty Wind, delivered with a knowing wink, draw on the creators’ fond respect for folk and Americana, similar to the musically rich film O Brother, Where Art Thou?, an invention of the Coen Brothers (of whom Moock is also a fan) that spawned an unprecedented roots music revival all its own. Although the unprecedented popularity of the film’s soundtrack had a positive outcome in that it gave a significant boost to bluegrass and folk performers old and new, Moock refers to the O Brother phenomenon with trepidation. “I don’t know what the long-term effect of that is. I don’t know if it’s just sort of a passing interest that people have, like the thing that happened with swing music a few years ago, where [afterwards] everyone sort of puts it on their shelf.” At the same time the film spurred a roots music boom, it eventually turned into something of a backhanded compliment to the Deep South originators of that sound, with the film’s complicated and multi-layered critiques of stereotypes that, though smartly done, influenced a fad that ultimately cannot help but sit a little funny with Moock. “It reminds me of these stories of Woody Guthrie coming to New York. Somebody wanted to put him in a show at the Rainbow Room where he was all dressed up in a hillbilly outfit with a straw hat singing old dancehall songs for a bunch of wealthy New York sophisticates, and [Woody] just walked out on it.”

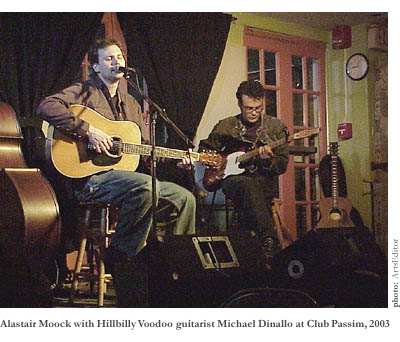

Among the several live engagements on the horizon for Alastair Moock are his first performances abroad, where he’s scheduled to play a few dates in Norway with his touring partner, guitarist Michael Dinallo, former member of blues revivalists The Radio Kings and the core of Hillbilly Voodoo (a rhythm ‘n’ country combo featuring Boston R&B legend Barrence Whitfield). Moock looks forward to the enthusiasm of European audiences, among which, ironically, there is often more interest in and respect for American roots music than in its own country. Moock notes that this imbalanced ratio of foreign and domestic appreciation is not exclusive to American artists. When studying in Zimbabwe for a semester during college, Moock had the opportunity to see musician Oliver Mtukudzi, whose fame in his home country is little, but who has become a huge star in the States through the exposure of World Music CDs (specifically those on the Putumayo label).

Between the live dates and writing his next album, Moock has been keeping himself busy. But he’ll never be too busy to return, whenever possible, to the Boston area, where his music first took root, and from where his creative path continues to grow, outward, into the open ears and minds of all those who share his love of the past and hope for the future.