Jerry Beck generates a bright idea with the ease of someone flicking a light switch on when entering a dark but familiar room. He automatically knows, from years of entering his imagination, exactly where to reach in order to avoid knocking a nearby picture off the wall, so to speak. The thing is, his home away from home, The Revolving Museum (TRM), lost its room in the Fort Point area of South Boston last year—which it had inhabited for free, courtesy of Bob Kenney at the Boston Wharf Company, since 1984—and is now moving into a new, unfamiliar space in Lowell that doesn’t even have its light fixtures installed yet.

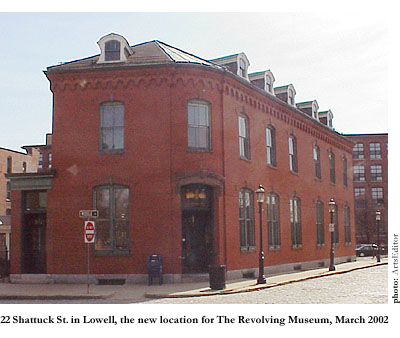

One nice thing about the new facility is its historic symbolism, says Beck of the stately but compact red brick building in the heart of Lowell’s downtown tourist district, built in 1859 by the Lowell Gas and Light Company. “It was being used,” he says, “for illumination and warmth then”—for converting coal gas to light and heat—”and I like to think that we will be using this space for illumination and warmth again.”

No question about it, the transformation of latent energy is Beck’s business—not the energy latent in fossil fuels, but in everyday people. Founded on a democratic faith in the equal distribution of intelligence and imagination, The Revolving Museum engages community involvement in its fanciful, site-specific, usually ephemeral projects.

A young, twentyish man named Jose Gonzalez, who’s helping Beck move into this new space in Lowell, is a case in point. Gonzalez has been with The Revolving Museum practically since the beginning. “Jerry came around my neighborhood looking for kids to help with Off Season,” he says, “a public art project he was organizing at Carter Playground in Roxbury [in 1988].” With the enthused help of Gonzalez and several other neighbor kids, Beck and some fellow conceptual artists from the Fort Point area created “a 200-foot baseball bat environment” that included an unusual batting cage and pitching booth, as well as a souvenir stand where locally relevant social problems—drugs, racism, and environmental pollution—were explored.

Several similarly interactive projects with young people from the tougher streets of Boston followed Off Season, including Night Train Lane (1989), in which TRM turned a dozen baggage carts from an abandoned South Boston warehouse’s railroad platform into curtained performance-art stages; the “collaborative multi-media installations,” known collectively as Flying Wing Series (1996-1998), that “happened” (for lack of a more current verb) at the fort on George’s Island in Boston Harbor; the nomadic I Scream Art Truck (1996), which went block to city block “providing interactive workshops in the visual, literary, musical, and performance arts”; and the recent Tunnel Vision project that documented the visual commentaries of 50 Fort Point artists on the gentrification of Fort Point, a renovated-warehouse area that has been home and studio to more artists than any other Boston neighborhood since the 1970s.

“In Boston, we revitalized public spaces not considered useful any longer, and we plan to do the same in Lowell,” recalls Beck, a tall, talkative, magnanimous man. “The whole history of a place has a psychic dimension that remains long after the people have left—you can feel that here in Lowell. What better place for people like us who want to revitalize public spaces? It’s ideally suited for public art works!”

Like many New England river towns, this small city was jilted long ago by textile manufacturers that migrated south with the Canadian geese and never returned. While other mill towns seem not to have recovered much from the commercial exodus, Lowell has come quite a way. The late congressman Paul Tsongas became a national legend for his successful effort, back in the 1970s when the place was a total wreck, to promote Lowell as an attraction to American history buffs and hi-tech entrepreneurs. Granted, the place is still a partial wreck, if the litter along the downtown canals, the decrepit housing on some streets, and some of the more bedraggled pedestrians are any indication. (One ranking official from a community development agency, speaking anonymously, says that the development of Lowell as a tourist attraction “has stabilized the city’s infrastructure without helping its citizens much.”) Nevertheless, it’s probably true that “Tsongas understood the importance of cultural development to economic growth,” as Jerry Beck notes. There’s a lot more going on here, a more palpable atmosphere of prosperity and well-being, than you’d find in New Bedford, Worcester, or Lawrence. And all without the place crawling with yuppies.

Some abandoned parts of town have been developed for more formal cultural activities than those that The Revolving Museum is interested in pursuing. Lowell’s gloomy old brick buildings, on the converging banks of the Merrimac and Concord Rivers, are used by the National Park Service, in memory of the textile mills and the French-Canadian girls who worked the looms. A sculpture park occupies a piece of downtown riverbank, in memory of native son Jack Kerouac, author of the Beat classic On the Road and the locally colorful Visions of Gerard. Next to the 200-year old Worthen Inn (where you can still get a beer) is the birthplace museum of painter James McNeil Whistler, whose mother must have rocked her share of winter nights away by the fireplace with the prodigy at her breast.

Opportunities should provide themselves to Beck and his troops at every turn of a corner in Lowell. Not every boarded-up storefront on Market Street has been turned into a convenience store by Latin Americans or Southeast Asians here, respectively, since the ’60s and the ’80s. There’s plenty of unspoken-for space all over town, much of it in neighborhoods inhabited by these more recent immigrants, who succeeded the Greeks and French Canadians. How many unclaimed looms lie in wait for a group of conceptual artists to make semi-surreal use of them? How many linguini grinders at the old Prince Spaghetti factory? How many canal-side mill-wheel houses? Maybe a group of French-speaking senior citizens in an assisted living center would like to cross cultural borders and get involved in a Jerry-rigged project in their assisted living center with the black-haired Cambodian children from the kindergarten around the corner.

Beck’s experience in exploring such realms of possibility has interested city administrators in the The Revolving Museum’s relocation. Says Paul Marion, vice-chair of cultural affairs for the city and assistant director for community relations at the University of Massachusetts, Lowell, “Having Jerry come here is a great huge step in our move to make Lowell a cultural hub.” A number of artists have moved into studios in recent years, Marion notes—including those ensconced in the four residential art studios in a renovated industrial building on Dutton Street, sculptor Patrick Pierce in a studio on Market Street, and others. “Jerry’s presence suggests to Boston artists who respect him,” adds Marion, “that they might look at Lowell as a place to work—and it’s close enough to Boston that they wouldn’t necessarily have to move here.” But it’s Beck’s public interest in straying with other artist-educators from the solitary studio to the crowded street that makes him especially valuable. He’s the kind of artist who could help the cultural wealth, if not the monetary wealth, start to trickle into the poorer neighborhoods.

One part of town that could use help from a public-art enthusiast like Jerry Beck is the run-down commercial Jackson-Appleton-Middlesex area—or JAM—not far from the MBTA’s commuter rail station on the southern edge of downtown. Sometimes the workplace of prostitutes and drug dealers, it includes a particularly promising vacant lot, where a warehouse once stood, that Marion’s office would like to develop. Beck and the city together are focusing on that area in their application for an economic development grant from the Massachusetts Cultural Council. “We just passed the first phase of the application,” says Marion. “So we’re hopeful.”

“We’d like Jerry to create a buzz in the JAM district,” Marion continues, “and give people a reason to explore the area.” If things go well, that buzz could conceivably lead to commercial enterprise in the JAM, which in turn would lead to the generation of revenue, which in turn would start to trickle, some of the funds—who knows—into the mortgages and training-programs of the most needy members of the community.

“That’s the first part of the grant proposal,” adds Marion. “We would use another part of the grant to sponsor sort of a downtown gallery night, bringing people in to see the New England Quilting Museum, the Brush Gallery [exhibiting the work of Merrimac Valley artists], and the Textile Museum, as well as The Revolving Museum”—all within gallery-crawling distance of the JAM area.

If past successes are any indication, the City of Lowell—with movers and shakers such as Jerry Beck and Paul Marion—is likely to succeed, at least to some degree, in this effort as well. In 1987 the city worked with the National Park Service to find a permanent space, in the Morgan Cultural Center near Boardinghouse Park, for the 100-member Angkor Dance Troupe, which performs traditional Cambodian dance. In 1988, under Marion’s direction, the Kerouac Commemorative sculpture park was constructed downtown on a riverbank, and the Kerouac legend continues to attract at least the lower-budget, alternative tourists. For several years now, the city has worked with the National Park Service to coordinate the popular Lowell Folk Festival, far and away the biggest attraction of all, according to the community development worker who spoke on condition of anonymity, and not necessarily the kind of event that raises the standard of living for everyone.

If past successes are any indication, the City of Lowell—with movers and shakers such as Jerry Beck and Paul Marion—is likely to succeed, at least to some degree, in this effort as well. In 1987 the city worked with the National Park Service to find a permanent space, in the Morgan Cultural Center near Boardinghouse Park, for the 100-member Angkor Dance Troupe, which performs traditional Cambodian dance. In 1988, under Marion’s direction, the Kerouac Commemorative sculpture park was constructed downtown on a riverbank, and the Kerouac legend continues to attract at least the lower-budget, alternative tourists. For several years now, the city has worked with the National Park Service to coordinate the popular Lowell Folk Festival, far and away the biggest attraction of all, according to the community development worker who spoke on condition of anonymity, and not necessarily the kind of event that raises the standard of living for everyone.

It’s one thing to ask how a community arts center of even the most conventional kittens-and-valentines kind could survive in prime real estate like that found on Shattuck Street; quite another to ask how an eclectic, conceptualist, community-organizing gang of education-happy “third generation Beatnik” artists like Beck could survive. “In a town the size of Lowell, we could work with every single child,” says the matter-of-fact idealist. “The scale here matches our ambition.” He was able to work with the City of Lowell’s Division of Planning and Development to purchase the building, presumably with some of the funds earned on the 50 studios he rented to individual artists in the Fort Point for 18 years. “We have a permanent home here! I couldn’t believe it when we got it either!” Still, Beck remembers that he has to raise $50,000 in the next three months to get TRM up and running in time for its July opening. There’s the catalogue to develop, for example, and there’s the radical renovation to do.

By the time The Revolving Museum does open in Lowell, with an exhibit of works about “home and family” by veteran associates of TRM, the town will be gearing up for the Lowell Folk Festival, which takes place for the entire final weekend of July. The Revolving Museum’s 22 Shattuck Street home, at the corner of Middle Street, is right in the middle of the festival, too—right around the corner from the small stage where bluegrass idol Alison Krauss played to a modest gathering—of pickers and fiddlers, mostly—before she hit the bigtime in the mid-’90s; and where, before he hit the big time, current blues sensation R.L. Burnside growled some libidinous electric blues so good that the group of Greek-American senior citizens from the nearby high-rise could not help but line-dance in the street. For two days straight, the kind of everyday people whom Jerry Beck likes to work with—surprising them with the unusual pleasures of their own previously untapped imaginative creativity—will be passing The Revolving Museum on their way to and from spectacles at the nearby stages in the JFK Plaza and Boardinghouse Park. That should be a good opportunity for Beck to generate some light and heat about his project. Some illumination and warmth.