In 1976, a decade after the events that end David Hajdu’s account of the folk music revival of the late ’50s and first half of the ’60s, I went to a saltwater-sultry Saturday evening party in Marshfield, Mass. My friends from work, at the Erewhon natural foods warehouse and production plant in the Fort Point Channel district of South Boston, were throwing the party in the sweet old colonial saltbox they shared on the shore, just across the road from the musty cove of some obscure inlet. After a hard week of forklifting bags of whole wheat flour, seaweed, and brown rice onto the massive industrial elevator, working the granola-bagging or nutbutter lines, and delivering the organic goods to food co-ops and macrobiotic restaurants around New England, they had spent their disposable income on beer and snacks and had brought out the electric guitars, drumsets, amplifiers, and microphones they’d bought. They were ready to jam.

At nine o’clock that evening, they finished a set of longhaired countryrock tunes by the likes of Fleetwood Mac, Jackson Browne, and Jerry Garcia; called the cuddling couples in from the fireflied yard, the giggling trios from the pine-scented porch; and turned on—of all things!—their television. It wasn’t time for us all to come on in and see Matt Dillon do right by the law, in a nostalgic re-run of Gunsmoke, but time for us to come in and see Matt’s homonymous namesake Bob, Dylan that is, broadcast live and in person with the angelheaded hipsters of the Rolling Thunder Revue from an outdoors stage somewhere in North America. After several years of seclusion that produced cryptic recordings of folk and blues relics—some of them, like those on John Wesley Harding and New Morning, sounding like medieval British bard chants, even if he’d just written them—Dylan was back on the scene in ferocious force. History was in the making.

At nine o’clock that evening, they finished a set of longhaired countryrock tunes by the likes of Fleetwood Mac, Jackson Browne, and Jerry Garcia; called the cuddling couples in from the fireflied yard, the giggling trios from the pine-scented porch; and turned on—of all things!—their television. It wasn’t time for us all to come on in and see Matt Dillon do right by the law, in a nostalgic re-run of Gunsmoke, but time for us to come in and see Matt’s homonymous namesake Bob, Dylan that is, broadcast live and in person with the angelheaded hipsters of the Rolling Thunder Revue from an outdoors stage somewhere in North America. After several years of seclusion that produced cryptic recordings of folk and blues relics—some of them, like those on John Wesley Harding and New Morning, sounding like medieval British bard chants, even if he’d just written them—Dylan was back on the scene in ferocious force. History was in the making.

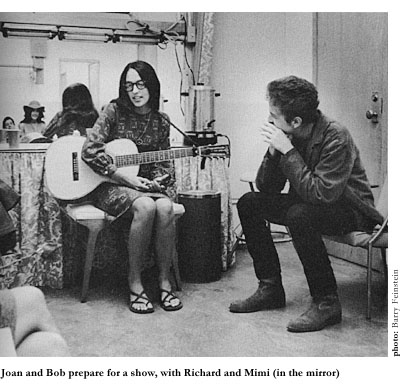

The Rolling Thunder Revue, touring not long after the release of Dylan’s great Blood on the Tracks album (a supremely accessible and sublimely poetic mixture of folk, rock, and pop), had already played a surprise gig in the high school gym in nearby Plymouth, another one up at a small venue in Portland, Maine, and no doubt others in New England that I never heard about. He seemed to be doing the goodwill gigs in celebration (consciously or not) of the sentimental-socialist Woody Guthried Americana that his tree-like career, however many branches it’s grown, is still rooted in. The infectious high spirits of those songs, softer and more bittersweet than either his furious mid-’60s folk-rock rants or his late-’70s born-again raves, looked a joy for him and Joan Baez to sing in duet at the top of their lungs, close-up on the TV we watched in my friends’ opium (or at least marijuana) den. They soared together on fabulous songs such as “Tangled Up in Blue,” “Simple Twist of Fate,” and “Buckets of Rain.” Even when singing the only really angry song on Blood on the Tracks (about the “idiot wind blowin’/ from the Grand Coulee Dam to the Capitol”), the climactic combination of songs “uniting poetry with elements of folk and rock and roll,” as Hajdu so astutely has it, brought warm blood and satisfying smiles to their expressive and handsome 35-ish faces. More than a dozen years since their voices had complemented each other on stage during Baez’s tours (at the peak of her and at the beginning of Dylan’s popularity), they seemed to find it easy to let “the tension between their styles [make] their presence together all the more compelling,” as Hajdu has it again, describing their early-’60s duets at Club 47 in Harvard Square, the Newport Folk Festival, the Folk City coffeehouse in Greenwich Village, and elsewhere. “Joan seemed to soften Bob,” he writes, “and he emboldened her; as the Hollywood fan magazines used to say about Astaire and Rogers, Baez gave Dylan class, and Bob gave Joan sex appeal.”

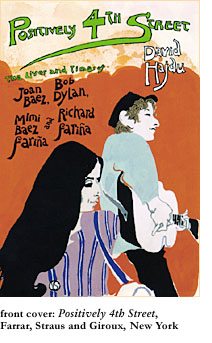

The title of Hajdu’s book, Positively 4th Street—referring to a Dylan song about the sort of sycophantic social-climbing you wouldn’t expect to find among les bohemes, who traditionally stake their collective identity on the rejection of mass-hysteria star-worship—resonates in every chapter. This entertaining and edifying book draws extensively on archival materials, including dozens of quotes from the early ’60s that are woven so gracefully into the prose as to sound like they were uttered yesterday. Hajdu offers us the nosy look we deserve (if we’ve bought any of his many recordings or been to his frequent concerts, for example) at the chameleon-like Dylan, balancing an appreciation of his talents (awesome productivity, fathomless inventiveness, courageous creativity) against a bemused assessment of his famous foibles (cruelty to friends as well as groupies, duplicitous greed for attention, calculated elusiveness). We get to peek in on him in his solitary studio bedroom in the Catskills, writing the insanely lucid rebel-cries found on Bringing It All Back Home, a perpetual joint of marijuana in his mouth, evocative clippings from the print media spread around on the floor, one bluesy folk-rock riff after another providing the rhythmic mold into which he’d pour the sort of beatniked and bombastic Euro-rap lyrics that made his mid-’60s recordings the classics they are. Then, when we’ve seen what went into the making of such scathing songs as “Like a Rolling Stone” and “Ballad of a Thin Man”—and into the good, sad love songs, too, like “She Belongs to Me” and “Sad-Eyed Lady of the Lowlands”—we are turned toward the unsavory elements of his character that allowed the diabolically existential songs to be made.

After she heard him (in a room above a Harvard Square storefront) sing “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall” and a few other originals from his first couple of albums, Joan Baez brought Bob Dylan under her wing. They even became lovers. It was 1962 or so and she was already famous. She’d dropped out of Boston University—Hajdu tells a great story about Baez and some fellow rebels boycotting the mandatory donning of freshmen beanies. She’d taken the Harvard Square coffeehouses by storm, conquered Greenwich Village, been recorded on national labels, and shaped herself in the pure, Pete Seegered image of a freedom-fighter. She loved the social-conscience protest songs Dylan did early on (partly under the influence of Guthrie and Seeger, but not without the encouragement of a girlfriend’s leftist family in New York) but, according to Hajdu’s convincing research, didn’t approve when he got restless with what he soon considered a predictable, one-dimensional representation of reality and turned his back on both protest music and the old British ballad forms Baez was still using. He “went electric” in more ways than one, suggests the author, shocking everyone who reached out to touch him.

Baez, of course, could be a jerk as well. In spite of that angelic voice and saintly reputation for nonviolent resistance, she gets perhaps the most rugged treatment of all in the book. We get a satirical, unflinching look at her aggressive self-promotion tactics early in her career. (Dylan borrowed, or stole, or “appropriated” a lot of his tunes, according to the biographer; but Baez copied entire acts, down to gesture and inflection, of such fellow folkies as Carolyn Hester, whose rising star was more or less eclipsed by Joan Baez’s.) And we get to leer at her seemingly hypocritical habits of conspicuous consumption after she’d hit the big time. (Yes, that was a Jaguar she was driving on her return to the Carmel, California, coast from marching in bare feet and sackcloth in this and that demonstration.)

Baez, of course, could be a jerk as well. In spite of that angelic voice and saintly reputation for nonviolent resistance, she gets perhaps the most rugged treatment of all in the book. We get a satirical, unflinching look at her aggressive self-promotion tactics early in her career. (Dylan borrowed, or stole, or “appropriated” a lot of his tunes, according to the biographer; but Baez copied entire acts, down to gesture and inflection, of such fellow folkies as Carolyn Hester, whose rising star was more or less eclipsed by Joan Baez’s.) And we get to leer at her seemingly hypocritical habits of conspicuous consumption after she’d hit the big time. (Yes, that was a Jaguar she was driving on her return to the Carmel, California, coast from marching in bare feet and sackcloth in this and that demonstration.)

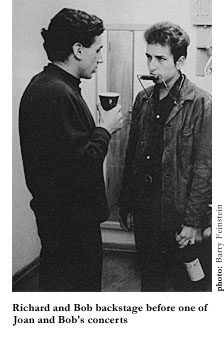

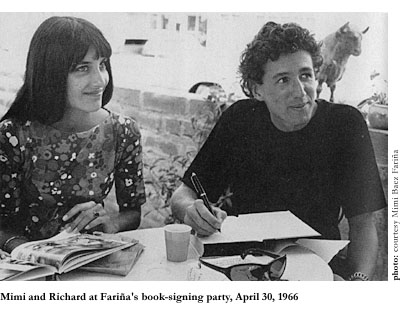

We also get a long, finger-lickin’ gaze at the marriage of the rakish Richard Fariña and the mouth-watering Mimi Baez Fariña (Joan’s younger sister), those two Latin-Celtic love idols who collaborated on duets for a couple of albums of their own. To the tune of Richard’s zippy dulcimer and Mimi’s spritely guitar, we hear them doing the raga-like instrumentals and singing the genuine-imitation old-timey tunes Richard wrote, such as “Pack Up Your Sorrows” and “The Falcon.” Back and forth we go in the book, from their stories (together and apart) to Joan and Bob’s (together and apart), wending our way, in untitled five- and ten-page chapters separated only by spaces, through the action-packed years of the folk revival that eventually was transformed, or maybe devoured, by the acid-rock renaissance of the late ’60s. We see Richard and Mimi soaring into orbit, famous together for their first album, Celebrations for a Grey Day, and famous apart (he for his new novel, Been Down So Long It Looks Like Up to Me, and she for being the sister of the famous Joan). They weren’t in orbit for long, of course—the book ends with Richard Fariña’s death in a motorcycle accident on the day he was celebrating the novel’s publication and Mimi’s birthday—but the creative work they produced is probably still available in a record—er, CD—store near you.

Luckily, the guilty pleasures of reading this gossip-packed book—it’s sometimes like reading the intellectual hipster’s extended version of a People magazine story—is relieved, and the pleasure-taker is redeemed, by Hajdu’s interest in the music’s cultural underpinnings. Between trips from Cambridge to Carmel, from Bearsville (New York) to Greenwich Village, and from Paris to London (following the intersecting trails of broken hearts and reparative records these people left), Hajdu watches the music grow. He explains the early fascination of the folk-revivalists with “rural vernacular music sung in untrained voices accompanied by acoustic instruments,” noting that they put a “premium on naturalness and authenticity during a boom in man-made materials, especially plastics,” creating in a sort of cerebrally anti-intellectual fervor a genre of informal, poor people’s music that “challenged conformity and celebrated regionalism during the rise of mass media, national brands, and interstate travel.” In a representative moment of mirth, Hajdu notes that “while Frank Sinatra was flying to the moon, Pete Seeger was waist deep in the Big Muddy.”

Between vivid descriptions of the Greenwich Village folk scene (according to one of the dozens of veterans quoted in these pages, “You couldn’t turn around without bumping into a guitar”) and backstage reports on the annual Newport Folk Festivals, we get to see Joan Baez appear on the cover of Time—her “ascetic grace and brooding musical persona” serving “as an antidote to the era’s sexualized, glamorized formula for feminine celebrity”; her sob-inducing covers of bittersweet ballads and Dylan songs working with her bare feet, long dark hair and big sad eyes to drive men mad. But for a higher-minded mood, we also read Hajdu’s irrefutable interpretation of the early-’60s folk music movement as the artistic expression of the politically charged times, especially around 1962-63 when “several of the nascent social movement’s core issues rose to the forefront of public discourse” with the publication of Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique, Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, and Michael Harrington’s The Other America—groundbreaking books on women’s rights, the environment, and poverty. Nothing could cap Hajdu’s argument better than his reminder that Dylan and Baez sang short separate gigs at the Lincoln Memorial before 250,000 nonviolent demonstrators at the very same March on Washington in 1963, where Martin Luther King, Jr. delivered his dream speech.

If Dylan is the only one of the four musicians here who will “go down in history,” that will be because he has written as many great songs (and sung them with searing expressiveness, making the maximum use of a rustic, some would say rusty, voice) as the rest of the best and most prolific American popular-song composers. Joan Baez’s early albums are sobworthy and sublime, to be sure; and the story of Richard and Mimi is very sexy and kind of inspiring. But it’s Dylan’s story that keeps the book together, just as it’s Dylan’s incredible creativity that does more than its share of the work in keeping the last 40 years of American music in respectable perspective. Hajdu’s inside look at Dylan’s evolution from quirky folkie to visionary rock-poet puts us in mind of Picasso going from the Blue period to Cubism and never coming back.

Dylan and Baez both turned 60 this year. That party in Marshfield ended 25 years ago this summer, right around midnight. The young woman I went to it with died a couple of years ago, rather than endure another psychotic episode that made it impossible to enjoy anything, folk music included. (I think I must have wished then that she might have been the Joan to my Bob, the Mimi to my Richard.) And coincidentally, I read a recent obituary on Mimi Fariña, dead of cancer at 56.

It’s nice to know where all the flowers have gone.