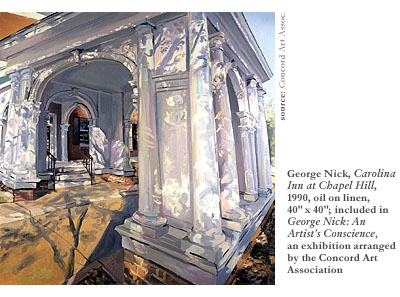

George Nick’s paintings render their subjects current and fresh, tightened with here and now, still happening. It is as if the works speak in present tenses. This immediacy, this strong sense of presence, makes them act upon the viewer directly and strongly: they do not wait patiently for attention, but approach one in a rush. Viewers can experience Nick’s works in two ongoing concurrent exhibits—George Nick: An Artist’s Conscience at the Concord Art Association from November 11th through December 23rd, and George Nick: New Paintings at Gallery NAGA from November 12th through December 18th, 2004.

The sense of immediacy these canvases reveal is particularly intriguing when we realize that these paintings frequently depict the old, the past—for example, the historic architecture of Back Bay in Boston—and they virtually never show any people or other living creatures, even though they are often streetscapes. Nick’s subject in painting is primarily the inanimate, particularly buildings and machines, including cars and planes. Devoid of human figures, the canvases seem to lack the element we viewers could most easily identify with and which, potentially, could help us perceive them as somehow close to us.

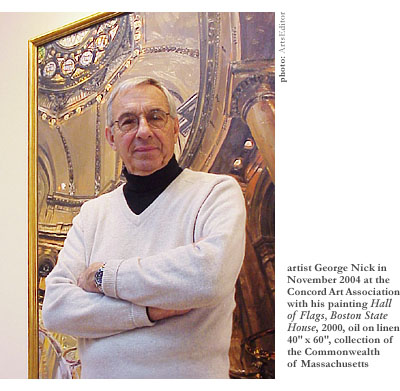

Having interviewed George Nick at his Concord studio in November, I cannot help but link his paintings’ immediacy with the artist’s direct and ardent mode of experiencing the world and his generally intense way of being. Nick responds to the environment vividly and rapidly. He is clearly fascinated by the physical aspect of reality and seems to absorb it as fully as possible.

Asked directly about his interests, he says that what attracts him as an artist is “the elusiveness and beauty of the world.” He also admits his passion for structure and construction of objects, which he connects with his father’s profession, carpentry. Apart from the abundance of buildings and machines in his works, the presence of an architectural scene by Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1720-1778) in Nick’s home testifies to his interest in the organization of the inanimate. “Piranesi knew a lot about structure,” he says with admiration for the Italian printmaker, whose dedication to depicting the ancient architecture of Rome resembles Nick’s avidity to paint the old buildings of Boston.

This enthusiasm for the world and the need to keep in touch with it directly makes Nick paint exclusively from life, on the spot. Unlike many other painters, representational or not, he is not willing to accept aid from other media (like photography) in his creative process. He rejects this as something that would mediate his encounter with the visual aspect of the world.

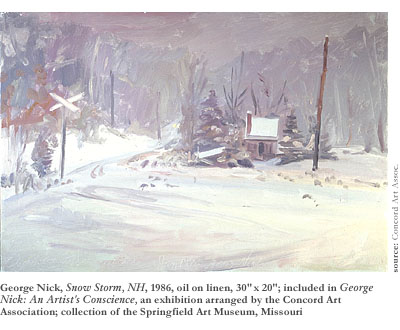

There is something moving about Nick’s commitment to painting from life—this 77-year old artist has been painting on the spot for years, sometimes during harsh New England winters. Settled in Massachusetts since 1969 and a long-time resident of Concord, he has learned how to deal with the cold. To endure low temperatures, he paints from a truck. Equipped with a heater, an easel, and painting tools, the truck is his movable winter studio. When he finds a site that he wants to paint, he stops, opens the truck’s back and, protected by a warm outfit, starts working. The results of this practice are paintings such as Snow Storm, NH—one of the few images in the exhibits that primarily presents nature—and Greenland, NH.

Looking at Snow Storm, NH, the viewer may recall J.M.W. Turner’s famous 1842 seascape Snow Storm: SteamBoat off a Harbour’s Mouth. Nick’s painting was created during an actual snowstorm, and likewise, Turner’s work, so the story goes, resulted from the British painter’s own experience of a storm, when he was allegedly lashed to a ship’s mast so he could observe this turbulent state of nature. Whether the Turner story is true or not, Nick’s work—due to the circumstances of its execution—reminds us of this vivid Romantic legend that accompanies Turner’s piece, and, through the story, reminds us of Turner’s painting itself.

As a whole, the exhibitions present George Nick as an artist who is especially preoccupied with the relationship between three-dimensionality and two-dimensionality. Of course, every representational painter explores this issue by the very fact of creating a two-dimensional equivalent of a three-dimensional experience. Yet in Nick’s paintings this problem is extravagantly emphasized. The encounters of dimensionality are often a subject of these works, almost as much as the buildings, cars, and other objects are.

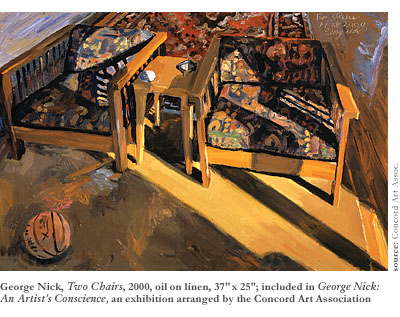

We do not need to study the works very carefully to confirm this statement. Let us look at, for example, the ground in Nick’s scenes. Whether it is a floor or a sidewalk, it frequently tends to tilt. Memory of Air and Space and, even more, Two Chairs exemplify this very clearly. We get the impression that the floors rise upwards, towards us. It is as if the represented—the floors—are striving for verticality so as to surrender to the actual uprightness and two-dimensionality of the canvas. At the same time, we feel a certain resistance to this movement, a contrary force that seems to push the floors towards horizontality, and creates the illusion of the third dimension. As a result, the paintings do not offer us a traditional perspective that would allow our eyes to rest in an illusion of depth. Rather, they provide us with a display of negotiations between the two-dimensionality of the canvas and the need to render the three-dimensionality of space and objects.

The way these two kinds of dimensionality coexist in Nick’s works recalls some works from the 1880s and 1890s in Western art—for example, Paul Cézanne’s landscapes and still lifes. Comparing Cézanne’s work from this period with Nick’s paintings, we may realize that in both cases the inanimate tends to slide towards the viewer. It is as if Nick virtually visited the end of the 19th Century. The period attracts him as the moment when two-dimensionality (flatness) started to manifest itself very forcefully in painting, as the time when painting clearly began to resist creating a three-dimensional illusion after many centuries of surrendering to this demand.

This highlighted pressure between flatness and illusionary depth in Nick’s paintings, resulting in the “slide” effect, is one of the traits that make his works look so immediate. “Sloping” towards the viewer, the cars, architecture, and pieces of furniture—as in 1928 Bugatti Type 35 B Works Car, Two Chairs, and Hall of Flags, Boston State House—appear to “move” close to him or her.

Another characteristic of these works that makes them so immediate is the visibility of brushwork, the emphasis on paint. The canvases invite us to contemplate their texture and distinguish between individual brushstrokes. The process seems to re-unfold before us, and thus the painting appears strongly related to the present moment. This emphasis on process and presence links Nick’s art with 20th Century modernism, in which, as Jonathan Fineberg phrases it, “the collapse of time into the present is a central issue.” The immediacy of his oeuvre proves that this painter, however resistant to numerous tendencies in contemporary art, has been in touch with some important artistic tendencies of his times.

George Nick: An Artist’s Conscience is a travelling exhibition, the first of its kind in the painter’s long exhibiting record. After leaving the Concord Art Association, the collection of paintings will be supplemented with several works from the exhibit at Gallery NAGA, the local dealer of Nick’s paintings, and will set off on a one-year journey. From January 20th through March 10th, it will be hosted by The Art Gallery of the University of New Hampshire at Durham. From April 23rd through June 5th, it will be at the Springfield Art Museum in Missouri. Then, from June 15th through August 1st, it will stay in the Eleanor D. Wilson Museum at Hollins University in Roanoke, Virginia. And eventually, it will reach the New York Studio School of Drawing, Painting and Sculpture, where it may be seen from October 27th through December 10th, 2005.

Nick says that as an artist his goal is to establish a sort of conversation between himself and those who look at his paintings, that he seeks responsiveness on the viewer’s part. So what we deal with is a pair of engagements: Nick’s paintings, records of his engagement with reality, aim to engage the viewer with the reality of painting. Given comments from the public I witnessed at the Concord Art Association, George Nick succeeds in this department—the viewers do respond to his art, often with excitement.