As the world’s media prepares for George W. Bush’s second presidential inauguration later this month, one naturally casts one’s mind back to those frenzied autumn days when he and John Kerry monopolized the front page of every newspaper on the eastern side of the Atlantic as well as the western.

Actually, to say they monopolized the front pages slightly overstates the case. Because, for one shocking day back in October, they were entirely usurped from the London newsstands by eulogies to the BBC radio disc jockey and all-round good guy John Peel, whose sudden death at the relatively young age of sixty-five, it is probably fair to say, occasioned the biggest wave of public grief since the death of Princess Diana (though not, I hasten to add, remotely rivaling it in scale). Even Prime Minister Tony Blair spoke of his “genuine sorrow” at the news.

Peel—who, incidentally, got his first job on American radio in the ’60s on account of his wholly fictitious claim to know The Beatles—was known as the godfather of the British music industry on account of the number of bands given their big break by having their records first played on his uniquely adventurous show. Naturally, journalists were fascinated to know which of all the countless thousands of records Peel had heard (more, perhaps, than anyone else in the rock and roll era) was his all-time favorite. Peel’s answer was always “Teenage Kicks” by the Undertones. However, when asked why, words tended to fail him, the best explanation he ever came up with being the very unsatisfying, “There’s nothing you could add to it or take away from it that would improve it.”

I find myself at a similar loss when people ask me what is so good about my own favorite band, the Undertones’ fellow Ulstermen, The Divine Comedy. After all, isn’t it, ultimately, one of those “if you have to ask you’re never going to know” questions? But, hey, surely an ArtsEditor reviewer can do better than that? Especially one with a full fifteen hundred words left to play with…

Well, let’s see. You won’t be surprised to learn that The Divine Comedy’s appeal has a lot to do with their music, which combines elements of, amongst other things, ’80s British indie, classical music, and French chanson. Every song on a Divine Comedy album tends to have a different stylistic identity, whose blend of influences somehow adds up to something far richer and more striking than the sum of its parts.

Despite this eclecticism, Divine Comedy albums are saved from that rather disjointed compilation album feel by the fact that their lyrics typically revolve around certain themes throughout—from water on Promenade to existential angst on Fin de Siècle to the life and works of Casanova on the album of that name, possibly the band’s finest.

Not that you would want to say that Divine Comedy albums are concept albums—the themes are too loose for that, and, though the lyrics are certainly clever, sometimes profound, sometimes funny, they are never obscure. Nor does their music ever become over-complicated or self-indulgent. They are, first and foremost, a pop band.

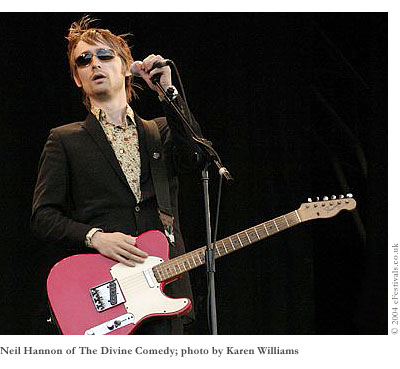

Actually, by “band,” I really mean an ever-expanding and contracting group of musicians centered around the ever-present singer, songwriter, pianist, and guitarist Neil Hannon. He recently completed a tour of the UK accompanied by just two others. The first time I saw The Divine Comedy, at T.T. the Bear’s Place a couple of years ago, the band was a four-piece—a line-up that proved surprisingly flexible on account of the members’ ability to change instruments at will. Even the drummer seemed able to play anything.

Alas, that concert was somewhat marred by T.T.’s lamentable PA system, by whose failings Hannon became increasingly annoyed as the evening progressed, eventually muttering darkly that he would “have to get drunk tonight.” There was also, I suppose, a certain lack of motivation playing in front of a couple of hundred people in the Boston area when he is used to playing in front of ten times that many in Europe.

Hence, I anticipated a wholly more satisfying experience when I tore myself away from the TV election coverage on November 2nd to go to see The Divine Comedy again at London’s Royal Albert Hall.

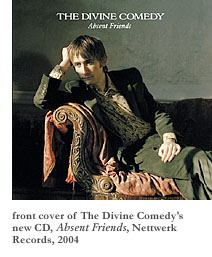

For the uninitiated, the Albert Hall is the concert venue in Britain—a vast, domed, somewhat snooty circle of Victorian opulence usually reserved for classical concerts. Accordingly, Hannon’s Boston quartet was to be augmented by an 18-piece classical ensemble in order to do justice to the richly orchestrated songs on the band’s latest album, Absent Friends.

The performance started without Hannon, the orchestra launching into a genre-hopping ten-minute instrumental suite, not exactly a medley but comprising themes from various Divine Comedy songs. I presume this piece had been written especially for the occasion, perhaps to reassure the various nervous-looking Albert Hall types who had apparently blundered into their habitual haunt unaware that there was to be no Mozart tonight.

The rich-looking old couple sitting next to me accordingly stood up and left as Hannon bounded on stage clad in his trademark suit and shades, and clutching two huge bunches of flowers, which he proceeded to toss handful by handful into the crowd during the opening bars of the band’s most famous and funniest song, “National Express.”

The rich-looking old couple sitting next to me accordingly stood up and left as Hannon bounded on stage clad in his trademark suit and shades, and clutching two huge bunches of flowers, which he proceeded to toss handful by handful into the crowd during the opening bars of the band’s most famous and funniest song, “National Express.”

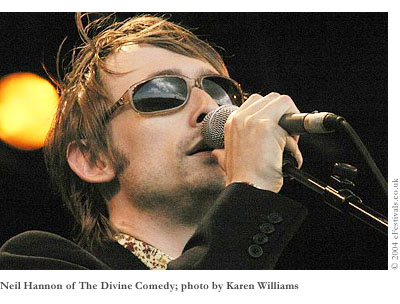

His baritone voice was rather flat at first, the can of Guinness at his feet testifying to the fact that he had other things on his mind backstage than vocal warm-up exercises. A couple of songs into the set, he explained the need to drink as, removing his shades and staring around the arena, he admitting to feeling terrified—before adding, with characteristic wit, that he wasn’t sure whether that was because there were so many of us, or because of what might happen in the U.S. election. Asking for the house lights to be turned on, he then enquired whether anyone wanted George W. Bush to win. Two brave souls out of over five thousand sheepishly raised their hands in defiance of Hannon’s glare.

Somehow the simultaneous occurrence of that era-defining event—a theme to which Hannon returned again and again (dedicating both “Generation Sex” and “Bad Ambassador” to Dubya)—added to the sense of occasion, of something historic happening. For this really was a big moment for The Divine Comedy. Hannon admitted that he had always wanted to play the Albert Hall, but that only now was the band big enough to fill it. Hence, tonight, he mused, had “distinct career highlight possibilities.” He admitted later that it was also his birthday.

That’s another thing I love about The Divine Comedy—the fact that Hannon is so communicative onstage. I hate those bands that just stand there and dutifully play their latest album without a word between songs besides the odd, muttered “thank you.” Even in Boston, Hannon had a fair bit to say for himself. Tonight, fuelled by the alcohol and the occasion, there was no stopping him. Midway through the first set, for instance, he produced a list he had copied from iTunes of what other people who bought his latest album had also bought, and proceeded to lambast those who had bought Europe’s The Final Countdown and—even worse—an unnamed Cliff Richard record. And who else but Hannon, when someone shouted, “We love you Neil,” would respond, “You’re the appointed spokesperson for the entire audience, are you?”

Nevertheless, the rather formal nature of the venue contributed, I felt, to a slightly flat atmosphere initially, as most people sat motionlessly in their seats, as they would have done for a classical concert. The sound engineer was also evidently more used to classical events, having a tendency to allow the band’s amplified instruments (especially the bass) to drown out the acoustic ones in a rather white soup of noise not wholly dissimilar to that produced by T.T.’s infamous PA system.

Perhaps Hannon, too, sensed the lack of audience energy, encouraging everyone to enjoy a G&T during the interval in order to make the second half of the performance “a whole lot more enjoyable.” Judging from the ensuing crushes in every bar (and, my, there are a lot of them!), I’d say a significant portion followed his advice, and it soon became evident that Hannon (who once wrote a song called “Gin-Soaked Boy,” after all) had also done so, as he clambered onto the lid of the grand piano for the climax of the first post-interval song, “The Frog Princess.” Sheepishly climbing down afterwards, he muttered that he wasn’t sure what had come over him (“perhaps the spirit of Engelbert”), but assuring his mother (who, it turned out, was in the audience) that he was not drunk.

The next song was the new album’s rousing title track, “Absent Friends,” which sounds rather like an outtake for a Western soundtrack. This brought Hannon to “another absent friend, the great John Peel.” Hannon admitted that Peel hadn’t liked The Divine Comedy one bit, but, nevertheless, proceeded to play, in his honor, a heartbreakingly beautiful rendition another of Peel’s favorite songs, Joy Division’s “Atmosphere.” It was a noble and deeply moving gesture.

After that, both Hannon (whose voice was, by now, soaring) and the audience became increasingly engrossed in the music, which drew from every nook and cranny of the band’s seven studio albums. The biggest pre-song cheer of the night came for the announcement of another track from the latest album, the magnificent “Our Mutual Friend” (which, admittedly, works better with the full orchestra of violins on the record, rather than the mere five permitted by Hannon’s concert budget), while the biggest post-song cheer came for the hilariously life-affirming “A Drinking Song,” during which it occurred to Hannon to order another can of Guinness from his roadie. Grinning from ear to ear, the singer then turned to thank the musical director of the ensemble, not because it was the end of the show but just because “I felt like thanking someone.”

His effusive and genuine thanks were also given to the audience before exhorting everyone to stand and sing along to the last song, “Tonight We Fly,” the most stirring affirmation of life’s beauty you are ever likely to hear (and, apparently, Hannon’s favorite of all he has written).

The atmosphere instantly intensified by an order of magnitude as the seats sprung into the upright position, and subsequent demands for an encore were deafening. The rather unwieldy group of musicians dutifully shuffled back onstage for two more songs, ending, as is Hannon’s custom, with “Sunrise,” another deeply moving song about his childhood during “the troubles” in Northern Ireland, which he dedicated to his watching parents. As the cheers finally really filled the massive auditorium, Hannon, his fear by now all transformed into glowing pride, turned once more to thank “his band” and admitted that he would have stood there forever if only “the rules of the building”—which insist everything be finished by eleven—had permitted it.

So that was that—the end of what was certainly the best concert I’ve ever seen. Indeed, it was so good that the glow lingered in my soul even as I followed the progression of the Ohio vote count. Whether the same could be said for Hannon is probably more open to doubt—especially given that his hangover would inevitably have begun to set in by then.

So have I succeeded in convincing you? Of course not. Only your ears could do that. But perhaps I’ve at least succeeded in convincing you to give them a chance. If so, besides listening to any one of The Divine Comedy’s albums, I would suggest that you get hold of a copy of Live at the Palladium, a DVD of a similar concert the band did earlier this year at another prestigious London venue. For the more financially conservative, there’s also a download available on the band’s Web site of their inspired cabaret version of the Queens of the Stone Age song, “No One Knows,” recorded live at that show.

What else can I say? Perhaps, after all, there really is no better way to put it than to say that there is nothing you could add or take away from The Divine Comedy that would improve them. And I can only conclude that John Peel, for all his unrivalled passion for music, must have been tone deaf.

Nor can he have read his 14th Century Italian poetry. For, if he had, he would know from Dante that heaven is the Divine Comedy. But I guess he knows that full well now. Rest in peace, John.