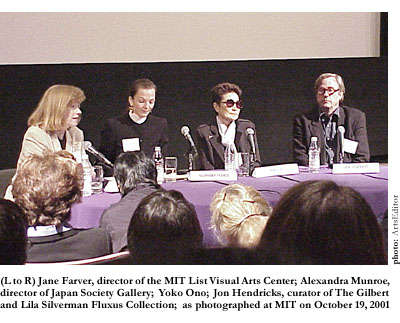

It’s not surprising that Yoko Ono—modest, reserved, mildly amused; an aging experimental artist in celebrity sunglasses—didn’t have much to say to the reporters poised with pens and pads at the press’ introduction to her show, Yes Yoko Ono, at the MIT List Visual Arts Center (LVAC) in October. She has never been one for longwinded explanations of her positions on public affairs and aesthetic issues. (That much is evident from a tour of her respectable and edifying retrospective.) She would probably prefer to have one-on-one conversations with individual people, like she reportedly did on the subject of her laptop one ordinary Friday in November with the lucky customer who answered the highly participatory Telephone Piece—an ordinary “princess-style” phone perched on a pedestal in the gallery.

Yoko was already a minimalist of few words when she emerged in New York in the late 1950s and early ’60s, and an outspoken and provocative minimalist at that, letting the cryptic declaration suffice in lieu of the turgid dissertation. Her potent, anti-poetic condensation of elemental phrases served her moral penchant for social criticism from the start, long before she and late husband John Lennon did their honeymoon-hotel Bed-In at the height of the Vietnam War, posted their billboards bearing the simple message WAR IS OVER! /IF YOU WANT IT in New York and London, or sang the blunt and rousing refrain to “Give Peace a Chance” over and over with a chorus of peaceniks and flower children—documents of which are all on display here.

One of the prettier and more yielding language-laden pieces from that pre-Lennon period, Ono’s Sales List (1965), presented at the LVAC as a poster on the wall, consists of an alphabetically outlined series of such invaluable and priceless items as

“G. garden sets

a. a shallow hole for moonlight to make a pond

b. a deep hole for the clouds to drip in

c. an elongated hole for fog ways”

Similarly, her 1965 performance piece, titled Morning Piece—in which she set up shop at a card table on a Greenwich Village rooftop and put shards of broken glass on sale, each shard labeled with the morning of a date sometime in what was then the future but is now the distant past (December 7, 1967 and July 22, 1987, for example)—has been documented in photographs on display on the wall and in a plexiglass case full of the actual absurdist relics. It goes without saying that no one could now afford to buy either of these decidedly unsubtle critiques of the capitalistic obsession with putting a price on everything.

Yoko only nodded when one reporter at the press conference observed the importance of language to such examples of her conceptual art. And in general, when she did speak obligingly in response to a question, the slightly breathless tone of her measured phrases betrayed a trace of nervous panic: a trait characteristic of certain punsters and poets, prone to say startling things off the top of their heads for fear of going speechless for good.

Nevertheless, the reporter’s observation hit the nail on the head as squarely as the participating spectators did at the 1961 happening where Painting to Hammer a Nail was created. In this early performance-art spoof on the conventional marketing and cerebralization of abstract art, Yoko invited the spectators, one by one, to approach the white canvas she’d mounted on the wall and, with a bang or two of the provided hammer, to contribute a nail to the work. Forty years later, the small wall work hangs on the wall of the LVAC gallery, its two or three dozen rusty nails as rooted in the white canvas as the rigorously irrational practice of performance art is in the art world.

Nevertheless, the reporter’s observation hit the nail on the head as squarely as the participating spectators did at the 1961 happening where Painting to Hammer a Nail was created. In this early performance-art spoof on the conventional marketing and cerebralization of abstract art, Yoko invited the spectators, one by one, to approach the white canvas she’d mounted on the wall and, with a bang or two of the provided hammer, to contribute a nail to the work. Forty years later, the small wall work hangs on the wall of the LVAC gallery, its two or three dozen rusty nails as rooted in the white canvas as the rigorously irrational practice of performance art is in the art world.

Next to it, in the large LVAC gallery space, is Half-a-Room (an installation of dirty-white kitchen furnishings all missing a half), and just around the corner is the hilarious participatory piece titled Amaze, which consists of a large transparent-plexiglass labyrinth, neither of whose two walkable halls leads to the toilet waiting at the middle of the maze, its wood-grained seat down as it would be in the politest of homes. This piece, in turn, is dangerously close to two dark alcoves in the gallery where films from the late ’60s are forever looping, both of them, like Amaze, bent on bringing us out of our culturally instituted obsession with pretty personal appearance, on cleaning our minds, as it were, and on providing a respite from complication. One of them boldly and unflinchingly features a series of rear-views, so to speak, of bottoms, butts, derrieres, and biscuits—close-ups of the buns of her models in forward motion. The other, the well-known Fly, documents the feverish, hand-wringing explorations of a few ordinary houseflies across the lovely terrain of a young woman’s body in nude recline—in and out of an ear, around and about a nipple, across a rippling landscape of ribs. The sight itself is something outrageously basic to behold, but it’s accompanied by a hair-raising soundtrack of Yoko’s orgasmic yelping and distraught screeching, suggesting the interior monologue of the housefly, the subconscious divagations of the dreaming woman, or both.

Not far from there, on separate large screens, loops footage of another performance piece from that period—Cut Piece (1965)—in which the young Yoko sat on a Carnegie Hall stage and had audience members come up one by one to snip away at her clothing with scissors until, serenely beautiful with her long hair and luminous womanly skin, she was nearly nude. An ambiguous, multi-faceted statement on the sexual vulnerability and objectification of women, Cut Piece continues to address stereotypes of submissive Asian women.

Not far from there, on separate large screens, loops footage of another performance piece from that period—Cut Piece (1965)—in which the young Yoko sat on a Carnegie Hall stage and had audience members come up one by one to snip away at her clothing with scissors until, serenely beautiful with her long hair and luminous womanly skin, she was nearly nude. An ambiguous, multi-faceted statement on the sexual vulnerability and objectification of women, Cut Piece continues to address stereotypes of submissive Asian women.

Like a lot of her language play, the very title of the show, “Yes Yoko Ono,” lifts a lot of mental weight with very little exertion, anticipating the glib headlines of skeptical culture vultures tempted to title their reviews, “O No Yoko!” Although the title is lifted from the step-laddered participatory piece at her mid-’60s show in London that attracted John Lennon to her, it seems to deflect the criticism of those who think either that she tore John away from the Beatles or that she’s a no-talent purveyor of cheap surrealism.

Some of Yoko’s humor must come from the Zen emphasis on detachment and mirth found in her Japanese roots. It shares convenient common ground with the European-born or -influenced conceptualists she worked with in her New York youth, including Marcel Duchamp and John Cage. And it recalls a lucid declaration, from her January 23, 1966 “Lecture to The Wesleyan People,” excerpted on a wall of the gallery, that “art can offer…an absence of complexity, a vacuum through which you are led to a state of complete relaxation of mind. After that you may return to the complexity of life again, it may not be the same, or it may be, or you may never return, but that is your problem.”

Yet this trail of cultural associations does not convey the humor and serenity of Yoko Ono’s visual (and sometimes aural) art. It must be seen and heard to be believed. In the very first gallery, for example, against the far wall—see those two substantial cairns of beachstones, similar in size and color? On the floor in front of one cairn is the label “mound of joy,” and on the floor in front of the other cairn, the label “mound of sorrow,” and equidistant to both mounds toward the middle of the gallery floor is a cairn of smooth gray beachstones roughly double the size of the joys and sorrows, suggesting that this is what our joys and sorrows add up to in the end. We may have experienced them to their fullest intensity, but now they are memorialized inertly by this dumbfoundingly delightful and drearily deadpan conceptual art work. This one is called Cleaning Piece, and it includes a pungent piece of advice, in a caption on the wall: “add a stone each time there is sadness” and “each time there is happiness” and see what they add up to. To practical sorts they might add up to nihilistic artsy-fartsy nonsense, making use of no actual artistic skills per se; to others, the piece will call to mind the magical inspiration of Zen koan, haiku, and other abbreviated language-art forms from the Far East.

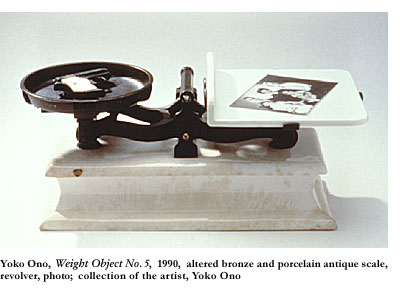

The same may be so of the two sets of scales on display in glass cases, titled Weight Object No. 1 and No. 5. One scale balances a silver handgun (loaded only symbolically we hope, and with coincidental reference to the means of John Lennon’s demise) on a round black pan against a black-and-white photo of the perfect American 1950s family on a square white pan—the tranquil and violent in juxtaposition. The other, a spiderlike black antique set of scales that must have been purchased at an alchemist’s auction, balances a serene bronze sphere and an antique door-key. The handgun and the photo apparently weigh the same, as do the iconographic sphere and door-key, reinforcing once again the distinctly Eastern message of the nearby Cleaning Piece—that the wise person in retreat from the passions of the world will give equal weight to all manifestations of earthly reality.

Maybe after she joined up with John Lennon, Yoko Ono lost some of her edge. Maybe she went and turned herself into some kind of Andy Warhol freak-show performer, always getting her face in front of the camera and her simple defenses of anti-war sentiment into the media’s microphones. Or maybe she couldn’t help it—maybe the media turns famous people into one-dimensional caricatures, especially if they’re quiet and flamboyant at the same time like she is. But if Yoko had been more of a talker, or if the American public had had more knowledge of 20th Century art and politics, she and John might have had more influence, might have sent fewer eyeballs rolling. Henry Kissinger might have done his own public Bed-In for peace with one of his “trophy chicks” instead of working with Nixon to bomb Cambodia on Christmas Day.