It’s an egregious inelegance that after having proffered an evocative, intimate, inspiring exhibition of artistry, even the most well-intentioned of museums often dump its patrons out onto the doormat of a gift shop. The Peabody Essex Museum of Salem, Massachusetts, a gleaming tower of clean, gorgeous minimalism, isn’t immune to this, yet its galleries and presentations repudiate any outright overture to crassness a gift shop might invoke. It’s still just a gift shop, though.

It’s where I find myself ambling about at the conclusion of It’s Alive! Classic Horror and Sci-Fi Art from the Kirk Hammett Collection, a spectacular exhibit (at PEM through Nov. 26) curated by the longtime Metallica guitarist/gatekeeper of genre artifacts. The exhibit is a traveling adaptation of Hammett’s 2012 compendium, Too Much Horror Business, charting his lifelong passion for the imagery, objects, atmosphere, and inclusivity of experience that horror, science fiction, and fantasy cinema has provided fans since its silent-era origins (and yes, the book is available here, just beyond my fingertips).

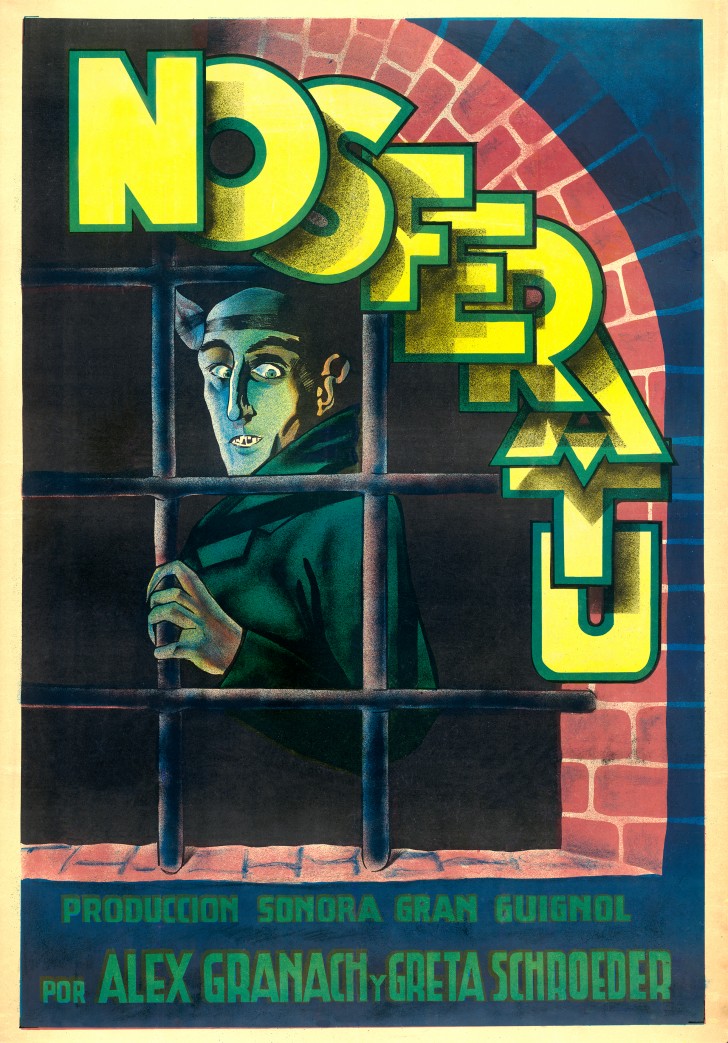

Immediately upon the exhibit’s entry, Hammett stakes his connoisseurship. The first film poster is a 1931 lithograph of F.W. Murnau’s Nosferatu for its Spanish release; in it, light (the sun?) cuts through the bars of a castle window, casting shadows across Count Orlock’s panicked, rat-like visage for most probably the last time. The emphasis on sickly green and yellow typography stands in contrast to most of the film’s prior monochromatic depictions in media. Its uneasiness sets the tone for the rest of the collection, which unfolds, for the most part, in harmony with the historical evolution of the genre.

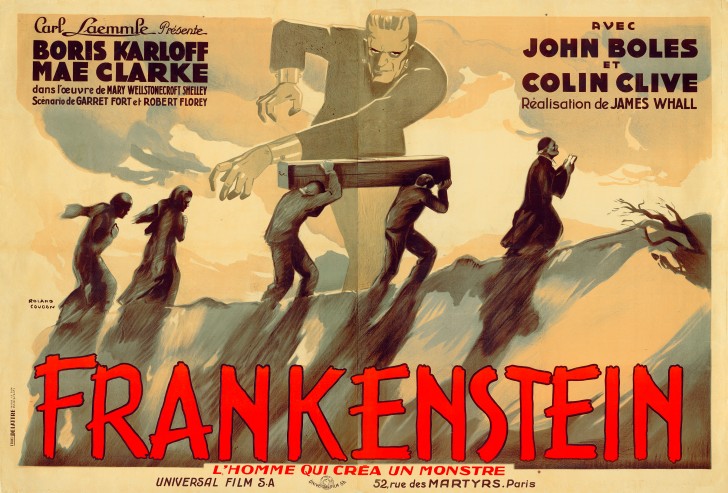

If James Whale’s 1931 Frankenstein is the iconic standard-bearer of horror, its representative posters here are anything but standard. The most striking of these is from France, yet feels vaguely of Stalin-era Soviet Union propaganda; an illustration of Boris Karloff’s monster as a ghostly puppet master hovers over a wind-swept funeral procession, replete with priest, pallbearers holding a coffin aloft, and mourners, all in silhouette. It’s oppressive and emotionally manipulative in a way that Universal’s American posters—catering to a more fragile, Depression-era audience—couldn’t be. The stories behind the acquisition of these prints is often as compelling as the design, and the exhibit is intent on telling them. A massive Frankenstein three-sheet, for example, discovered in a boarded-over projection room is precisely where an item such as that should be unearthed, inextricable in its enhancement of the film’s mystique.

The 1930s’ gothic, expressionistic aesthetic is well-represented in the collection, matched only by the monster-as-metaphor, B-movie allegories of the international post-war community. Albert Kallis’ art for 1956’s The She-Creature—a sultry, billowy robe-clad woman, frozen in a tortured sway, flanked by a mutated, biped beetle—is purposely bathed in a red haze, the color, the accompanying placard tells us, “elicit[ing] emotional association with dominance.” A one-sheet for Great Britain’s Day of the Triffids from 1962—a film Hammett admits, in a video interview that loops for strolling visitors, “was something I wasn’t supposed to be watching and was part of its allure” (and one he credits with igniting his fascination with horror)—depicts the frenzied assault on a shrunken humanity relegated to the margins of the frame by nature itself, arriving this time in the form of lumbering, man-eating plants who blast out of the poster’s center. A ferocious Mothra print is scarier than anything found in the actual 1961 Toho film (and whose tagline paints the giant insect as perhaps hormonally forlorn, declaring that it’s “Ravishing A Universe For Love!”).

Outside of chronology, works are grouped for discourse, too. An Italian print of Roman Polanski’s Repulsion, alongside one for his Rosemary’s Baby and Hitchcock’s Psycho, visually conjures the emerging female sexuality tropes—both enticing and disturbing—that dotted the horror cinema landscape of the 1960s. Psycho manages a twofold manifest: its poster is also a reminder of graphic designer Saul Bass’ stranglehold of influence on the aesthetics of movie marketing from the 1950s to today. The juxtaposition of 1958’s I Married A Monster from Outer Space’s stark sparseness with the opulence of 1946’s La Belle et la Bête (not strictly a genre film, but rife with assured gothic horror imagery) stirs discussion around how disparate design styles feed similar themes of romantic terror.

Examples of exploitation and drive-in horror art of the 1970s are disappointingly threadbare (although Hammett’s got those, too, as revealed in his Too Much Horror Business book; they just didn’t make the cut for the PEM show), and the absence of the works of genre pillar Vincent Price is surprising, but Hammett’s collection traffics in the unexpected. Indeed, the most dynamic and evocative prints of It’s Alive! are those belonging to films on the fringes of popular consciousness. A towering lithograph of 1933’s The Ghoul (depicting a pallid arm emerging from a sarcophagus) and a series of prints for 1936’s The Walking Dead, both nearly-forgotten Karloff vehicles, are among the exhibit’s most powerful and haunting. Tod Browning’s searing Freaks (1932) gets the Belgian treatment (it’s title here is Barnum), yet retains the film’s pendular “us vs. them” composition, a cavalcade of circus performers menacingly filling the poster’s frame.

Posters aren’t the only curios on display either. The collection includes a life-size figure of Karloff from 1934’s The Black Cat; the green velour suit of the alien sentry from 1953’s Invaders from Mars; and the Zapatron generator, the perennial laboratory prop of any self-respecting mad scientist from the Frankenstein films and beyond. The crown jewel of this category, though, might just be the 1932 oil on canvas portrait by Geza Kende of Bela Lugosi—dapper in a gray, tailed suit, hand on hip—that the Dracula actor had commissioned himself. For those bound to the image of Lugosi as vampiric and angular or that of a withering, late-career drug addict, the painting is mesmerizing in its conveyance of Bela’s elegance and warmth. One leg of the exhibit is designed to emulate a Cold War-era living room, adorned as such with a couch, a coffee table, and a black and white television playing the 1956 sci-fi pulper, Earth Vs. The Flying Saucers. A photo mural of a nuclear family huddled in a stocked bomb shelter blankets a whole wall, an echo of a time when governments were the scariest thing going.

I place Hammett’s book carefully back on the gift shop’s shelf, for at museums, one should do things carefully. I’m compelled to deploy my gaze somewhere else, to the glass wall that looks out onto Peabody Essex’s indoor courtyard, which is being dressed to look like a banquet hall halfway between 2001: A Space Odyssey and The Crow. Kirk Hammett himself—the musician and horror conservationist, curator of a most impressive, comprehensive art collection—passes by and, without breaking stride, confers upon me “the nod” of recognition, one obsessive to another. I return the nod, besotted, and think how vital a museum gift shop can be in consummating an exhibit’s allure.