“Is this blue plastic mop bucket on the sidewalk a piece of conceptual art?” I wonder on climbing the stairs of the old brick building that houses the Mobius Art Gallery on Congress Street in the Fort Point Channel area of South Boston. It seems more likely that an actual janitor, sans Dadaist training in the placement of mundane objects in unexpected contexts, has placed it here near the curb, after draining its dirty dregs into the storm sewer, and has gone back inside to hang his mop upside down in the closet. But I am here to see a bona fide European conceptualist give a talk, and you can never be sure what someone like that is up to. The mop bucket, influenced by Duchamp’s famous urinal, might be Milan Kohout’s version of the commercial sandwich board—an obscure piece of anti-advertisement.

It’s a Monday night in mid-December, and Mobius is far from the center of the mainstream cultural activity in Boston. Are the Pats playing on TV tonight, live from Foxboro? Are the Celtics or the Bruins bringing the throngs to their feet in the FleetCenter? It doesn’t matter, because this artists’ group, in existence for 20 years or more, caters more to the stream of consciousness than to the mainstream crowd. It’s just fine that no more than 20 people have shown up to sit in the bleachers of the black box theater and hear Kohout answer the question “Who Owns the Homeland?” that he has posed in his title. That’s roughly how many you’d see at a lecture at Harvard tonight, on something like sentimentality in Dickens or AIDS education in Zimbabwe.

The homeland in question is Central Europe, including the Czech Republic and Croatia, the two countries the Czech native has visited in the past year on peace- and art-making missions for the Roma (a.k.a. gypsy) people. Notwithstanding the splintered ethnic and linguistic subgroups at war with each other in the Balkanized 90s, the majority of the people in that part of the world are the various, sensible-shoed Slovaks whose cousins populate the Upper Midwestern cities of Cleveland and Chicago. They differ from one another enough to go to war over territory, yet have more in common than they have as a whole with the people they are united in their traditional, unquestioning hatred of—the gypsies, who comprise three or four percent of the population. Kohout’s title question is rhetorical. It goes without saying that the gypsies don’t “own” the homeland.

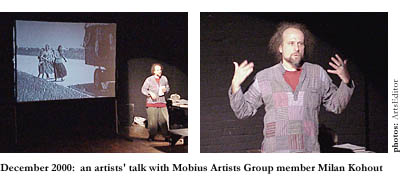

Frizzyheaded, wispybearded Kohout, dressed in baggy fatigues, black boots, and a Central American campesino’s overshirt covering all but the collar of the burgundy jersey beneath it, wades into his passionate talk about the plight of the Roma in a thickly accented, expressive English punctuated by a good deal of gesticulation. Even with the renovated warehouse’s water-boiled heating system driving the temperature in the theater dangerously close to triple digits (or so it feels), it’s a fascinating pleasure to hear Kohout go on and on and on about these pariah-prone people, first about the history of their oppression, then—with a vivid video clip about them reeling on the wall—about their colorful culture, and finally about Kohout’s own history of involvement with them.

The Roma have roamed Europe, says Kohout, ever since they scattered from their Indian homeland around 1,000 A.D. Their culture, flavored by Islam during a long layover in Persia (present-day Iran, at one time known more for its poetry and carpetmaking than for its patriarchal government), “crashed” into European culture, he adds—much as the present-day Arabs in France and Turks in Germany have. From then on, everywhere the gypsies roamed, the cops were sure to follow, through the Middle Ages, Renaissance, Reformation, and Age of Enlightenment, denying them all civil rights in Holland, England, and Portugal, expelling them when convenient, and finally gassing one and a half million of them in German concentration camps in the interest of creating an ethnically clean society. That may be why one Romany proverb, adding a nice simile to Hobbs’ famous “Life is brutal, nasty, and short,” has it that “Life is like a child’s shirt: dirty, ragged, and short.”

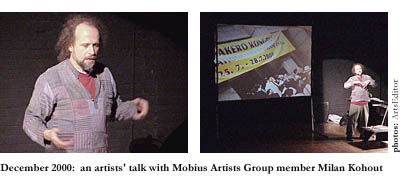

Maybe it takes an avant-garde spirit like Kohout, himself a Czech native and an accomplished performance artist, to appreciate the anarchic style of the Roma people. (The design of the gypsy flag that Kohout presents in his slide show, featuring the image of a red wheel on a green ground below a blue sky, alone should please any symbol-mongering artist’s eye, avant-garde or not.) The trickster artist is attracted to a people who, regarded as secretive, shifty, childlike, and parasitical, have always been even more mistrusted than artists by conventional society.

Kohout never says it during his impassioned, empathic, two-hour presentation, but the power of the flamenco-like gypsy music crying from the sound system in the background suggests that the nomadic detachment from the mundane obligations of civilized life—a detachment granted to children without resentment, but never to adults—has kept these swarthy and humble people free to express themselves. They don’t seem to have gotten the gray message implied in the grip of the grim industrialists. Anything but subdued, the Roma balladeers seem to have taken the best of the traditions they’ve roamed among (Spanish, Sephardic Jewish, Arabic, Central European) and have done in music what Ezra Pound says poets do in poetry: They have “purified the dialect of the tribe.” The barefoot children filmed in their muddy hovels cannot help but dance on the dirt floor for their curious visitor with the video camera when their grinning, gap-toothed uncle plays the accordion like that! Music and dance seem to be all they have to live for after the videographer records a father of four in a neighboring hovel say that he’s just done time for stealing potatoes, followed by a mother of 10 barefoot children who exclaims, “I want to have 10 more!”

The yearning sound of a woman singing to the accompaniment of a spare but fiercely plucked Spanish guitar sounds even more bittersweet when Kohout recalls for us an ordinary Czech citizen telling him that he was “glad for what Hitler did to the gypsies.” And the unrestrained wailing at the videotaped funeral of a dark-haired man has the same kind of emotion as the music, oddly accented by the image of an unlit cigarette in one folded hand of the corpse. Life is impossibly rough for the Roma, and seems unlikely ever to be less so for a nomadic people in a regimented society, but Kohout flashes another proverb on the screen—”God will never let the Roma people die”—that gives them some tragic hope.

Kohout’s talk is meant to tell us that there’s more hope than the video would suggest, in fact. His defense of the Roma people is part, he adds, of a larger countercultural movement, kind of like that formed by white radicals to support disobedient African Americans during the civil rights movement in the U.S. And like the civil rights movement, it seems to have had some impact. Kohout, who snorts that he used his “master’s degree under socialism to wipe my ass,” was expelled from Czechoslovakia in 1986 for doing illegal human rights work. But he was able to get a significant grant later, from the post-Soviet government of the Czech Republic, to do rights-related performances and fight racism with his art. “Like a gypsy,” he says of the period between his exile and prodigal-son return, “I lost my sense of time.”

One sure sign of hope for some reasonable assimilation of the Roma is the “gypsy conference” Kohout was invited to attend in Prague in July 2000. The proceedings may have shown symptoms of the gypsy culture’s shall we say fluid sense of time, says Kohout. “People kept breaking into song” among the orderly rows of seats at ordinarily sober times, he chuckles. But the Roma have the attention of the government, which “wants to look like it’s treating them well if it’s going to be accepted into the European Economic Union,” and there are a few admirable activist Roma leaders speaking clearly on behalf of their people. Maybe the systematic oppression of the Roma will abate for good.

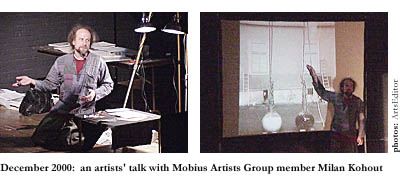

Kohout gave voice to that hope when he went to the sixth International Theatre Festival in Pula, Croatia, in the summer of 2000 as well. In 1999 he’d already performed, on a live Prague TV news broadcast, a public-space piece meant to “create a xenophobic feeling of anger in spectators” that could then be identified and purged. He tore down a symbolic wall between Slovak and Romany cultures to commemorate the 10th anniversary of the democratic revolution in Central Europe. Now, before a live outdoor audience of casual-looking onlookers in Croatia, he was dangling two enormous glass beakers, one full of white paint and one full of black, by pulleys from the branches of two trees in a park. One “godjo” (that’s the Roma word for someone who isn’t a gypsy, like the Yiddish word “goy” for someone not Jewish) was holding between his teeth one end of a long pole, and a “gypsy” (again, that’s the Godjo word for the Roma) was holding the other end between his teeth. The tension caused by the effort to keep the symbolic stick of peace off the ground built with each indication that the stick might be dropped by one or the other—by accidents perceived or real, on purpose or not. With each increase in tension, either the white or the black beaker descended on the pulley closer to the ground—this next to a building whose closest two windows Kohout had whitewashed and blackwashed, the white close to the white beaker, the black close to the black. Soon the Slovak or the Roma—it doesn’t really matter which—could no longer hold up his end of the stick and the inevitable happened. Both beakers crashed to the ground and spilled their polarized paint, illustrating in blatantly symbolic terms the clumsy causes of ethnic strife. Where the paints blended, the ground became gray, the color of neutrality.

It was child’s play—socio-absurdist European performance-art theater with a fresh moral edge to it. Kohout let a lot of people play the crazy stick game that day under the two trees in Croatia at the theater festival. The people enjoyed trying their hardest to keep the peace between them. They did contortions in their effort to keep the stick off the ground. The crowd stood close to them in a ring, smiling and sighing. Then, when everyone had had enough fun, in a final, innocent, heartbreakingly clownish act of reconciliation, Kohout climbed up and washed clear the white and black windows, so that the peaceable crowd of Slovaks and Romas could actually see past the surfaces of the windows, through the clear glass panes, and into the depths of the building. Beautiful young black-haired gypsy girls in colorful traditional costumes—long pleated skirts, white blouses, and colored halters—came out of nowhere then, just like they might to a town that hasn’t been expecting them, and began to move to some very lively music that the townspeople ought to be happy for.