The journalists who’ve given the DeCordova Museum and Sculpture Park’s 50-year retrospective of Boston painting lukewarm reviews must not have read Nicholas Capasso’s essay in the catalogue Painting in Boston: 1950-2000, which supplements the exhibit of the same title, on view through February 23rd. One of the curators of the exhibit, Capasso writes a trenchant 28-page history of “Expressionism: Boston’s Claim to Fame” that serves as a pretty good rationale for the exhibit if not as proof of its value to local artists and intellectual historians. Describing the nationwide abandonment of Regionalism and Social Realism by the painters of the early 1940s interested in “figurative painting that sought to express emotional content about the human condition” (rather than what they may have considered superficial social and political content), he notes that worldly painters everywhere, borrowing from Munch, van Gogh, Picasso, and all sorts of German and other European Expressionists who’d migrated to the States, sought to communicate “what a subject feels like rather than what it looks like.” Leftist politics be damned, everyone in the shadow of Orwell said after Hitler goose-stepped to the podium and Stalin gave socialism an ugly human face that it was time (paradoxically) to lose ourselves in a passionate individualism.

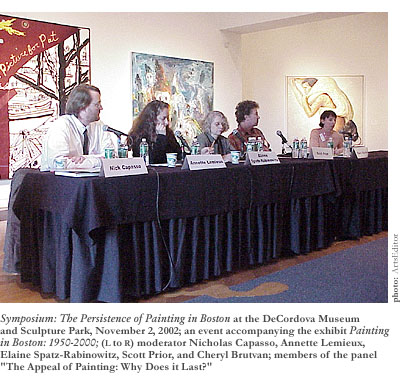

Dwelling in a relatively international city (albeit far from the blinding limelight of New York City), such Boston painters as Jack Levine, Hyman Bloom, and Karl Zerbe (the only European immigrant among these three Jewish humanists—the other two being American-born) practiced their own form of Figurative Expressionism that continues to beget offspring in the art schools and private studios of Boston. It wasn’t Capasso’s job to let on, in moderating the second of two panels in the November 2nd symposium for the exhibition, that he perceives with such clarity the unity of concerns and styles that characterize the seemingly disparate work of all those he includes in one or another faction of the Boston Expressionists. Rather than pontificate about Boston painters’ tendency to depict “human figures seen alone or in narrative vignettes”—formally distorted, richly colored, and ambiguously spaced against sometimes murky and shallow backgrounds, expressions of a “heady humanism” intent on giving the viewer a visceral sense of the painter’s agony and ecstasy more than a sense of the subject matter in the painting—Capasso facilitated a laid-back discussion of “The Appeal of Painting: Why Does it Last?” Hoping to elicit imaginative responses from his four panelists—for the pleasure and edification of the paid-up attendees in the folding chairs—Capasso chose not to ask a general question about reasons for the persistence of painting but to ask particular questions of particular participants, and then to let them wing it in a sometimes meandering, often amusing manner for five or ten minutes each.

Citing the past 20 years of multimedia dominance over the art world—installation, digital, photo, performance art and the like—but allowing that there’s been a resurrection of self-identified painters of late, he asked Cheryl Brutvan, the Beal Curator of Contemporary Art at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, if painting (an international language of sorts, not always requiring translation) was big on the international scene—as if he didn’t have an incredibly well-informed answer himself. He asked multimedia artist Annette Lemieux, visiting faculty member at Harvard University this year, what role painting plays in her work these days. He asked Western Massachusetts photo surrealist painter Scott Prior, who two years back had a solo exhibit at the DeCordova, whether (or how) he applies digital technology to his “traditional” paintings. Finally, Capasso offered Elaine Spatz-Rabinowitz, self-deprecatingly “famous in Boston” art teacher at Wellesley College since 1988, a chance to say why she, as a “widely exhibited” painter, believes a medium that has been declared dead more than once can possibly keep rising from its own ashes like a phoenix to live once more.

Citing the past 20 years of multimedia dominance over the art world—installation, digital, photo, performance art and the like—but allowing that there’s been a resurrection of self-identified painters of late, he asked Cheryl Brutvan, the Beal Curator of Contemporary Art at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, if painting (an international language of sorts, not always requiring translation) was big on the international scene—as if he didn’t have an incredibly well-informed answer himself. He asked multimedia artist Annette Lemieux, visiting faculty member at Harvard University this year, what role painting plays in her work these days. He asked Western Massachusetts photo surrealist painter Scott Prior, who two years back had a solo exhibit at the DeCordova, whether (or how) he applies digital technology to his “traditional” paintings. Finally, Capasso offered Elaine Spatz-Rabinowitz, self-deprecatingly “famous in Boston” art teacher at Wellesley College since 1988, a chance to say why she, as a “widely exhibited” painter, believes a medium that has been declared dead more than once can possibly keep rising from its own ashes like a phoenix to live once more.

Though hesitant to speak frankly at first to a roomful of strangers whose likelihood of making future donations to the DeCordova might hinge on the thoroughness and elegance of their replies, sooner or later the participants managed to loosen up and let fly whatever giddy, wry, irreverent one-liner came to mind, and sometimes even to sustain a train of thought all the way to some surprising station. Herself not there as representative of the artistic temperament, Brutvan noted in sensible tones that if painting pure and simple wasn’t the dominant medium on the international scene, well, then at least references to painting in other media were: large-format photos that mimic the traditional full-length portrait painting, for example, or collages that include clippings from art history books (Botticelli’s Venus surfing toward the boardwalk and whatnot). And besides, noted Brutvan, photography would have killed off painting a century ago if it were ever going to happen.

Immediately striking the enfant terrible pose that seems to come naturally to her (restless, suspicious artiste always on the lookout for flatfooted dullards), Annette Lemieux complained good-naturedly about the constraints of the panel’s topic, sneering at the preference of talk about paint over talk about imagery (from the first panel of the afternoon), and said she works in whichever medium seems at the time to offer the best way to get an idea across, whether it be public icons like flags and crosses she’s photographed or the autumn-twilight starlings silhouetted on a huge flowing white fabric in a recent exhibit at Harvard University’s Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts.

When his question came, Scott Prior—whose painting (Nellie in Backyard) of a little girl naked in her lush backyard swoons into the recesses of the frame—let Capasso know in no uncertain terms that he doesn’t consider himself a “traditional” painter, and that he trained to be an astronomer till turning to printmaking in the late ’60s on seeing some miniature Flemish-Renaissance etchings but has adapted his scientific training in recent manipulations of imagery on a computer screen (hence the pixellated, as opposed to pixilated, look of his paintings). Prior likened the modifying impact of digital technology on painting to that of photography a hundred or more years ago—astute enough as insights go but not worth the price of admission.

This wide-ranging response left Elaine Spatz-Rabinowitz, probably the most verbal of the four, to speak eloquently to the visceral pleasure of applying the paint (borne out by a look at Nevada Darkness, her textured flat-landscape abstraction on a nearby wall), to sing the praises of “big fat brushes” and “long slender sable brushes” used in this “sensuous medium,” to evoke the pleasure of squeezing viscous paint from the tube, and to celebrate the painter’s freedom to employ dissimilar influences (Van Eyck and Sheeler for her) in single paintings that serve as static, silent, salvaged apprehensions of reality—yes, and objects for contemplation—in a freakishly frantic world, in lives that otherwise would seem too short and bereft of much meaning.

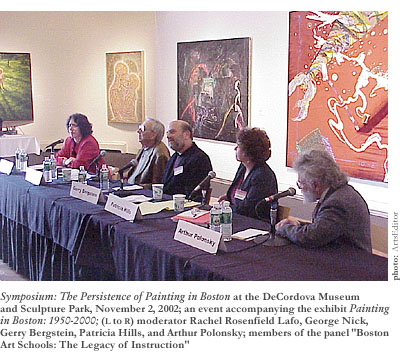

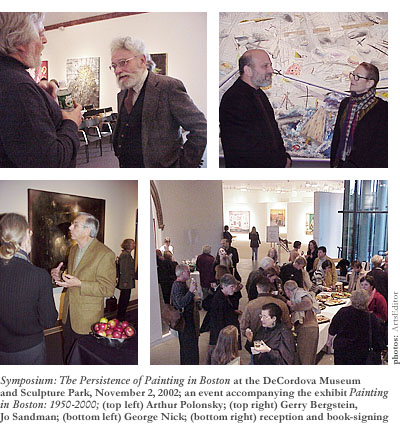

Even when the four panelists had had their say and questions from the admiring audience had come meekly forth (providing opportunity for some delightfully silly responses from Lemieux and Prior), Nicholas Capasso never did say much—and neither had DeCordova’s Director of Curatorial Affairs, Rachel Rosenfield Lafo, in her moderation of the first panel of the day, “Boston Art Schools: The Legacy of Instruction.” Inviting her four well-seasoned guests to reflect on their own local experiences in the learning and teaching of the painting trade, Lafo asked each of them—most of them veterans of the student bodies and/or faculties at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (SMFA) and Boston University (BU)—to identify their influences and to estimate to what degree they attempt, consciously or not, to hand on inherited traditions to their own students. This made for more freely associative responses than those the humor-hungry audience would hear from Capasso’s younger set of artists in the second half.

Rambling back and forth across some 50 or 60 years of residence in Boston, Arthur Polonsky—former apprentice to Ben Shahn, student of Expressionist Karl Zerbe at the SMFA, and longtime teacher at BU—called his former employer a “fortress of conservatism” but praised the technically oriented teachings of Zerbe at the SMFA—understandable coming from a gestural painter attempting to let the content emerge (however indistinctly) from the inside rather than have it arrive in a package from the outside. Because of Zerbe’s teaching, people went to Polonsky to see how to keep white paint from cracking after it’s been applied to black paint. (If his 1959 painting Marine Samson is any indication, not in paintings of white kittens entangled in an unraveled ball of black yarn.)

George Nick, double-degree recipient from Yale University’s famous studio arts program and for 30 years a teacher of painting at the Massachusetts College of Art, noted that he still relays to students answers to questions he asked his own teacher, the somewhat legendary Edwin Dickinson, back in New Haven—technical “nuts and bolts” answers, like those that obsess Polonsky, regarding the importance of keeping the palette clean and of knowing how best to mix colors; decidedly not heady, jargon-happy subjects such as the primacy of perception and that sort of thing, but honest-craftsmen-in-corduroys topics you’d expect from a realist who moved to Boston to paint Back Bay townhouses like the one in the solid, trustworthy, if not terribly provocative painting (titled Commonwealth School) he contributed to the exhibition. He expressed dismay at the sort of posing done at the SMFA—where cultivating a disturbed artistic temperament has long been a required course of study—and nodded, like Polonsky already had, to the influence of David Aronson at both the SMFA and BU.

Not that far past 50 yet, Gerry Bergstein seemed like a young rebel by comparison to the 75ish Polonsky and Nick—but that’s partly because he maintains a refreshingly youthful humor in much of his work. (His large tromped l’oeil, featuring ladders, hamburgers, and assorted other juxtaposed objects of pop-iconic significance, might give as much pleasure to the looker as it gave giggles to its maker.) He nodded to two influential teachers he had during his student years at the SMFA—Henry Schwartz and the recently deceased Barnet Rubenstein—and said that he himself, in his teaching work at the SMFA, tries to push students in different directions (like Rubenstein did) using techniques learned from Schwartz. This elicited a brief reminiscence of painting teacher Henry Schwartz asking if he’d paid his “eclectic bill” yet—itself almost worth the price of admission.

The lone scholar on the panel, Patricia Hills—Art History Professor at BU and author (respectively) of two published and one forthcoming book on modern American masters Stuart Davis, Alice Neel, and Jacob Lawrence—said she finds it useful to tell her students who all the big-time artists studied with. She recognized the importance for young artists to strike poses in defiance of their masters, so that rather than cultivating clones and having “little Gerry Bergsteins running around,” the next generation might discover new territory on its own. She cautioned against the sort of us-versus-them rivalries that at one time led teachers practically to prohibit their students from visiting exhibits of figurative painting.

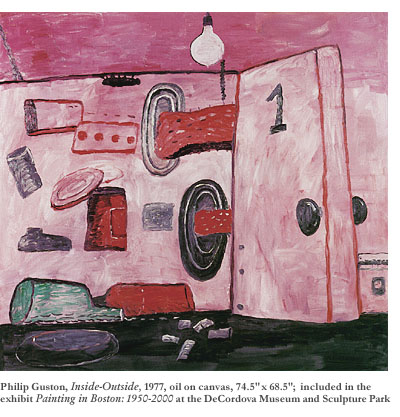

Toward the end of the first panel, talk turned toward the work and influence of the best-known painter to set up an easel in Boston during the 50 years covered by the exhibition. Philip Guston—the painter who turned first from Realism to Abstract Expressionism in the ’50s and ’60s and then, bucking the anti-figurative trends of the art world, back to a creepy, cartoon-like Realism in the ’70s while teaching at Boston University—is represented by at least one painting in the exhibit—Inside-Outside. It’s one of dozens of his late paintings that combine Expressionist and Realist influences still at work in the eclectic brushes of Boston painters.