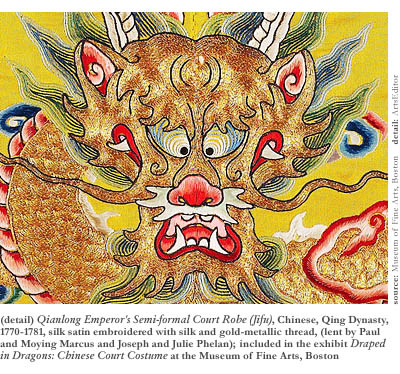

He has the head of a camel, the horns of a deer, the eyes of a rabbit, and a neck like a snake. He has the claws of an eagle and the paws of a tiger. And he is not the result of a cloning experiment gone awry. These are the constitutive features of the Chinese dragon—a powerful symbol of China and Chinese history. Known as the king of all beasts and a herald of spring, the dragon may be most strongly associated with the principle of yang, standing as an emblem of maleness and creation. Dragons are found on most of the textiles and clothing associated with the Chinese emperor and his courtiers—they embellish robes worn by court officials as early as the Tang Dynasty (A.D. 618-907), with subsequent dynasties continuing the tradition, connecting themselves through the familiar imagery to China’s past.

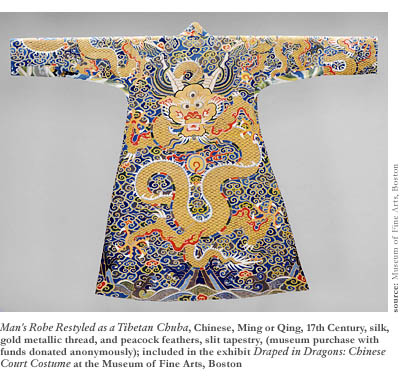

In Draped in Dragons: Chinese Court Costume, the inaugural exhibit in the newly relocated and renovated Loring Textile Gallery at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, stunning examples of these semi-formal jifu—known in the West as the “dragon robe”—are displayed amongst other examples of imperial dress, costume accessories, portraits, furniture, and textiles of the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911). A collection of the museum significantly augmented by the generosity of several local collectors, the exhibit represents a rare opportunity to glimpse the magnificent artistry of these objects. Reaching beyond the scope of imperial trappings, Draped in Dragons also offers insight into the lives of the men—and women—who wore them. Such rarities as an early Qing Dynasty robe made of silk and gold-metallic tapestry bless the exhibition and are a delight to the eyes—although, be warned, they are likely to make you bemoan the dreariness of your own wardrobe.

In 1644, the birth of the Qing Dynasty was owed to the battle prowess of the Manchu invaders of the North. Bribing their way through the Great Wall and taking advantage of an already existent melee instigated by a Chinese rebel army, the Manchu seized the capital at Beijing. Overthrowing the Han-Chinese of the Ming Dynasty, the Manchu launched what was to be a thriving, highly bureaucratic reign. Chinese traditions established and maintained since the ancient Han Dynasty were merged with newly introduced Manchu traditions. As the existent civil administration system met with the Manchu military structure, traditions also merged in the development of official dress for the imperial court. The Manchu rid imperial wardrobes of the full-sleeved Ming robes and tailored their dress to better suit their extraordinary nomadic horsemanship. Robes were fitted closer to the body and sleeve cuffs were designed to be pulled over the hands for protection when riding.

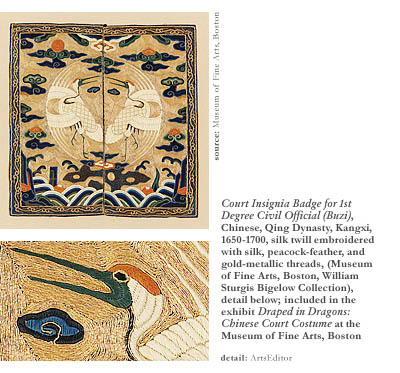

Intact, however, remained many symbolic aspects of Ming dress. Preserving the Confucian ideal of emphasizing a clearly defined hierarchy, court clothing played an important part in maintaining order and served to identify the ranks of officials. Buzi, square badges appliquéd to surcoats, identified an official’s striation. These were often codified with animal representations—cranes, for example, represented the first of nine military ranks, while the egret served as a symbol of the sixth military rank. The representation of hierarchy within both the civil and military administrations was a highly regulated and distinct aspect of attire that was soon to be magnified exponentially with the reign of the emperor Qianlong in 1736.

Court dress also provided infinite opportunities to pay reverence to the emperor, exalting him as the representative of the divine on earth. The dragon was, of course, an integral part of that iconography, and an endlessly complex iconography it was. An interesting fact: forward-facing dragons were more important than sideways-facing dragons. The levels of meaning and indication of rank in the painstaking minutia of the embroidery are vast.

From 1736 to 1795, the emperor Qianlong reigned in the Chinese empire. Literally writing the book on the standardization of official dress, the Illustrated Precedents for the Ritual Paraphernalia of the Imperial Court outlined every instance of magnificence and pretension required of official dress for the imperial family, the nobility, and civil and military officers. Color mattered. Shapes mattered. Certain jewels implied levels of rank. Certain beads were appropriate for the court necklace. Qianlong even explicated what summer robes could be switched for winter ones—a sort of fascist Mr. Blackwell.

Qianlong also brought back the twelve imperial symbols worn by the emperor for official state sacrifices—all the rage in 206 B.C. He reserved the symbols for the sole use of the empress and himself, as well as those to whom he gave the honor. Representing universal dominion, the symbols appeared in five colors, each color linked to one of the five elements and to one of the four cardinal directions. Yellow was the emperor’s color, as well as an indication of the fifth direction—the center. The twelve symbols included the sun disk, the moon disk, the constellation, and the mountain, all representing principal features of the universe and found around the robe’s neck. The dragon was the principle of yang; the pheasant, yin. Elements were represented by bronze cups, waterweed, millet, flames, and again the mountain, this time implying the element of earth. Finally, the sacrificial ax was the emblem of the imperial power to punish, and the fu character spoke for the power of judgment.

The finely woven tapestry robes of Qianlong’s reign showcased in the current exhibit were wrought in accordance with the highest imperial standards and continue to reverberate with seemingly all of their original gleam. One particular example, circa 1750-75, is bright yellow in color, hosting five-clawed dragons clutching the pearls of wisdom. Its color, decorations, and the appearance of all twelve symbols (as mentioned above) are elements consistent with an owner of imperial rank.

Hats, badges, small purses, belts, and jewelry are all examples of further adornments with the potential to convey prestige. The hats of imperial rank, for example, bore elaborate knobs with tiers of gilt phoenixes surrounded by pearls. The number of tiers and pearls indicated the rank of its wearer. Even the hat stands often upheld a level of utmost extravagance. All such accessories—and accessories to the accessories—can be found in Draped in Dragons: Chinese Court Costume amongst startlingly detailed furniture and portraiture.

Because textiles of this nature are extremely susceptible to fading from exposure to light, such items cannot be put on permanent display. These days, ancient dragons have to crouch in the darkness. Hence, Draped in Dragons is a rare chance to catch a glimpse of these magnificent mythical creatures; they will be in the limelight at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, through May 2nd.