Upon hearing his organ students play some rather daring improvisations before a panel of stuffy adjudicators at the Conservatoire de Paris, the late Romantic French organist and composer Louis Vierne [loo-wee vee-AIRN] wrote:

“Just for appearances I thought I should lecture them a bit on the difference between excess and propriety. But, deep down, I was laughing with them at the large dose of spicy sauce forced down those gentlemen who were used to listening to sweet tidbits and swooning with delight.” (From “Louis Vierne: Organist of Notre-Dame Cathedral”)

Vierne makes no secret of his appetite for dissonant, tongue-blistering sonorities—that is, what he affectionately refers to here as “spicy sauce.” His music, however, is not necessarily the hottest bottle of sauce in the pantry when contrasted with the products of his contemporaries. If innovation and avant-gardism tend to be what secure a composer’s place in history, why does Vierne’s music endure? To answer that question, we begin with some words on Vierne’s education and development as an artist.

As is the case with many trained composers, Louis Vierne’s early works show a direct assimilation of his teachers’ styles. From César Franck he learned to conceive sensual, expansive melodies undergirded by lush, stirring harmonies; from Charles-Marie Widor and Alexandre Guilmant he inherited a solid grounding in traditional structure and counterpoint. Later on, following a brief lull in compositional output around the turn of the twentieth century—perhaps busy with his newly-acquired marital responsibilities and high-profile job as the organist of Notre-Dame de Paris—Vierne brought forth his Second Symphony for organ. This piece began to stray from traditional constructions and reflects a distinct jump forward in his musical maturity, so much so that the renowned French composer Claude Debussy—a veritable innovator in the broader world of Western classical music—publicly praised the Second Symphony. Still, it wasn’t really until Vierne wrote his Sixth Symphony for organ in 1930 that he stretched the limits of traditional tonality to a great degree.

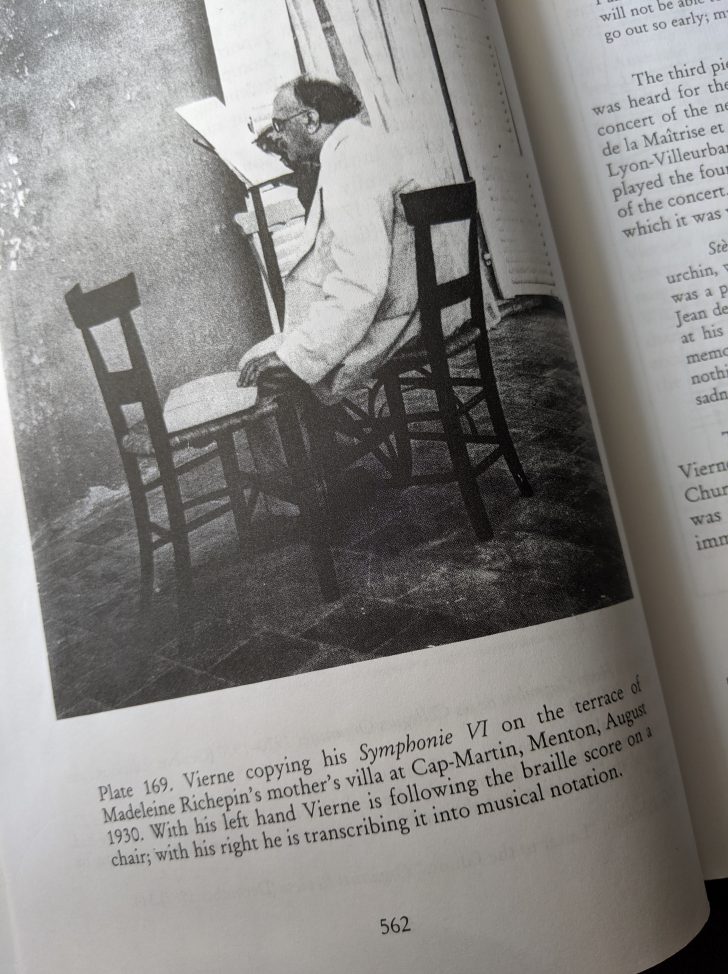

In any discussion of Louis Vierne’s musical output, it would be negligent not to also touch on a few details of his personal life. First of all, he was born blind. Although some of his sight was restored in an operation during childhood, he was only ever able to “get about, recognize people, see objects at a short distance, and read large print at very close range.” This would not, however, prevent him from pursuing a career in music. This was made possible in no small part by the Institut National des Jeunes Aveugles in Paris, the first school in the world designated entirely to the education of blind children. Vierne was neither the first nor the last visually impaired organist to hail from this institution; Louis Braille, the creator of the braille system, attended the school and was a skilled organist and cellist himself.

Aside from his blindness, Vierne was continually hampered by other difficulties in his life. He marked the year 1906 as “the beginning of catastrophes.” Such a designation seems to relegate the prior untimely deaths of his uncle, father, and two teachers as a mere hors d’oeuvre to the pièce de résistance of his unrelenting hardship, but such was the severity of his circumstance. In May of that year, Vierne stumbled in a hole that had been concealed by rainwater. His leg “cracked like a stick” and nearly had to be amputated. This could have meant an end to his career, but after two months of relearning how to walk, and several more months of relearning his organ pedal technique, he reported feeling “practically back to normal.” That practical normalcy lasted a whopping three months: in January 1907, he caught typhoid fever and nearly died. By his own declaration, it was his unshakable will to finish composing the last movement of his violin sonata that kept him alive.

Skipping his divorce, the deaths of his mother, his last teacher, his son, and his younger brother, in addition to his own continuously declining health, we arrive at the story of Vierne’s dramatic final hours. On June 2, 1937, after playing his “Triptyque,” Op. 58, in concert at Notre-Dame de Paris, he paused to prepare for an improvisation. What little sight he had left was fading quickly. “I’m going to be ill,” he uttered, before fainting and depressing the low E on the pedalboard. Moments later, he breathed his last. Listeners below in the vast cathedral nave assumed he was beginning his improvisation; in reality, the only thing beginning at that moment was his entrance into eternal rest—or so we can only hope.

In light of such a life, it’s no wonder that Vierne would gravitate toward a musical style amply drizzled with “spicy sauce.” He simply could not have released the anguish of such chronic pain and suffering with symphonies of mayonnaise on white bread. Nonetheless, Vierne was not stylistically ahead of his time, nor was he on the cutting edge of musical innovation. In 1913, Igor Stravinsky premiered his ballet The Rite of Spring, which, in tandem with its shocking choreography, induced a riot in the concert hall. That same year, Vierne was writing his Vingt-quatre pièces en style libre, which can only be considered a glass of warm milk in comparison. Even when limited to the sphere of organ composition (which historically tends to be rather like dial-up internet in the wireless age), Vierne does not prove exceptionally progressive: in 1931, for example, Charles Tournemire, an exact contemporary of Vierne, composed his Choral-Improvisation sur le ‘Victimæ paschali,’ a work at least as piquant as Vierne’s Sixth Symphony for organ which was published that same year.

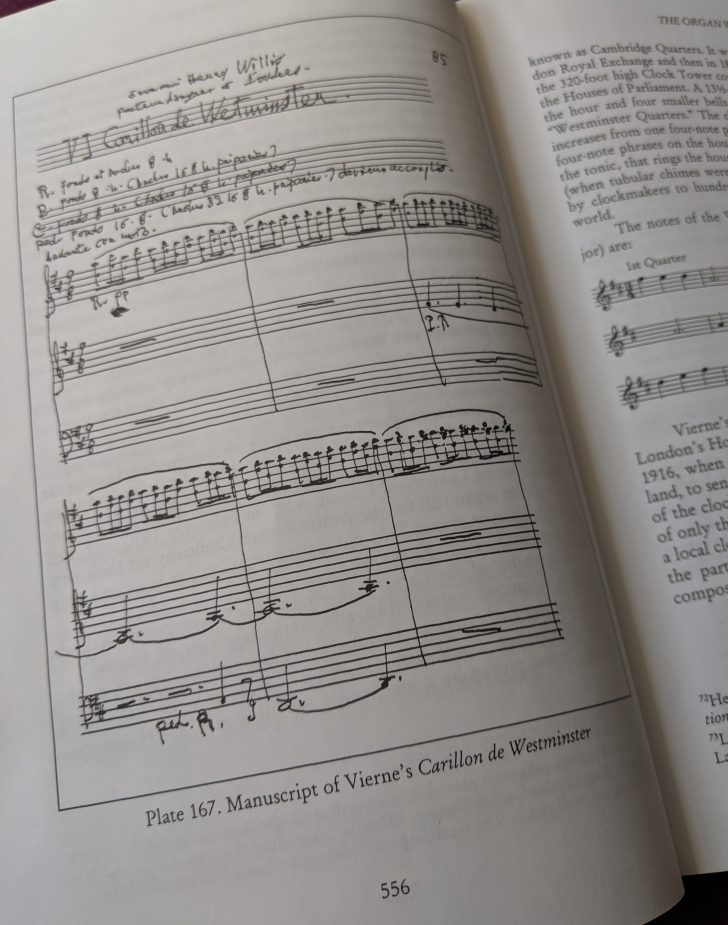

If Vierne wasn’t embracing modernism before everyone else, why does his music endure in the organist’s repertoire? I ascribe this to his talent for deftly flavoring familiar forms with a tasteful helping of modernity. In Vierne’s own words, he wanted to lecture his students on “the difference between excess and propriety.” Although he remarked, rather apologetically, that this was “just for appearances,” accounts of his teaching (in addition to analysis of his compositions) prove that he truly valued a solid grounding in traditional form and structure. In the words of one of his pupils, Maurice Duruflé, his mind was “classic” and “rational”—and who wouldn’t value such things amidst a lifetime of such constant upheaval? Nevertheless, from the crashing dissonant chords that lead to the final cadence of Vierne’s Carillon de Westminster to the playful, yet demonic, flourishes of the Scherzo from the Sixth Symphony, it is evident that Vierne loved his “spicy sauce.” It seems that it was only the “large dose” of such an additive against which he felt the need to caution his students.

Alongside this well-balanced blend of refined tradition and individual flair, one cannot ignore the sheer emotional power of Vierne’s oeuvre. In the same way that he faced his own continual personal trials, Louis Vierne’s music consistently shows resilience and optimism. His Third Symphony is an excellent example. The work is predominantly a storm of wrath, melancholy, and deceit, but the clouds eventually part in its final minutes to reveal an exhilarating, sunny conclusion. I find that this is not because Vierne is obligated to do so by tradition, but because the catharsis he has created is so thorough, there is no remaining direction to turn except upward.