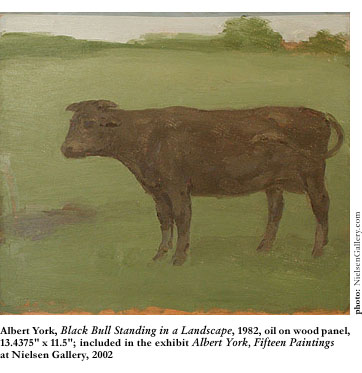

What, I asked myself, is that small, straightforward, old-fashioned landscape painting—of a black bull in a green meadow—doing on the first of two platforms in the stairway up to the second floor of the Nielsen Gallery on Newbury Street?

Isn’t this gallery known to exhibit the representational works (for the most part) of contemporary American artists such as Jon Imber and Maureen Gallace? The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston is where you’d go to see this kind of painting, over there between the Millets and the Homers. The kind that doesn’t shriek, scream, or screech; obscure, obvert, or obdurate; dismiss reverent treatments of subject matter as bourgeois denials of an essentially discordant earthly existence; or juxtapose anachronisms for a decontextualized antagonism.

Then again, works by a modern Long Island painter named Albert York are supposed to be on display through March 23rd. It says so in the publicity papers right down in the foyer for the exhibition—Albert York, Fifteen Paintings—and that’s his name on the wall as Director’s Choice. Maybe he’s kept to the old ways of painting in honor of the Anglophilial, pipe-in-the-den sound of his name. Albert York. Albert of York. Albert of New York.

But it’s a great little painting, I’ve got to admit. Sure, there aren’t any references in it to the maze of modernist mansions and mammoth malls (monuments to Mammon) that must be munching up the landscape just beyond that hay-scented meadow. But maybe that’s for the better. Here, after all, is an earthly creature, a black bull that’s really reddish-brown, in all its brute beauty presenting a broad, solid view of its left flanks in a mist-green pasture. Maybe he’s an icon of male fertility, a homage to admired past painters of rural charms. And maybe he’s just a bull. But mostly he’s a respectful, earthbound craftsman’s study, embodying the field of the painter’s vision, unconcerned (on his painter’s behalf) about the woes of the wider world. The woes of the narrow world are wide enough for the bull, brooding stubbornly alone under a thin blue sky.

Up the stairs a few steps, on the wall of the second platform, awaits another bucolic image rendered in a style not characteristic of much modern painting. It’s a Seated Woman with a Stork by a Pond in a Landscape just like the prepositional title promises in the caption. A country lass with blurred features sits in the green meadow by that silvery body of water, her square-necked, reddish-brown dress and plain brown straight hair parted down the middle as in days of yore. Serene, contemplative, and homely, she beholds the stork—an icon of female fertility this time—that is standing on one skinny leg just a few feet away without a worry in the whirled world. Granting credibility to the allegory, she holds a blue blanket in her lap in anticipation of the imminent baby. The blanket’s the same light blue of the distant sky. A somber, daring, unabashed sentimentality charms the mythical scene.

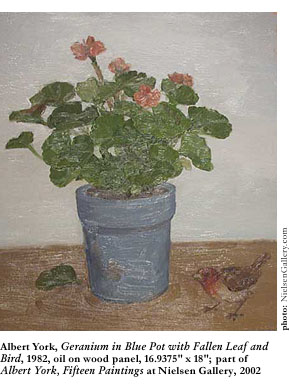

It’s hard to make it beyond the landing of the second floor into the actual galleries, because an excruciatingly ordinary painting on the wall demands attention. It’s a curious still life of a harmless house finch alighted on a table beside a pot of generous geraniums. Not far away on the table, a foot or so perhaps, just on the other side of the flowerpot that centers the picture, lies a green, fan-shaped leaf that has dropped a foot or so from its tendril to the table. The compositional relationship between the bird, the plant, and the fallen leaf speaks concisely and subtly to the spiritual relationship—the trick is to look at the picture long enough to hear it. The bird, as fickle as the bull is stubborn, looks mysteriously attracted to the fallen leaf—approximately as much so as the pregnant girl is to the miraculously accessible stork.

Nature, suggests York in these narrative pictures, provides peace and prosperity, if it’s domesticated by a farmer or a painter.

It’s nice not to be roaming an exhibit of shallow feeling, clumsy craft, and strident iconography, and a privilege to be able, at the top of these stairs, to turn either left or right. In the gallery to the right hangs the chilling pair of landscape studies, the very green Landscape with Two Trees and River and the very brown Twin Trees. Both offer subdued and charged looks not only at the landscape but at the kind of open-air painting artists used to gather in the fields of southern France and the Hudson Valley to do. In this room also can be found the joyfully homely portrait of The Gray Dog (similar in some respectful respects to the portrait of the bull), and the radiant larger painting of the Wildflowers in a Terracotta Pot, over there in the alcove where it can be alone with its power.

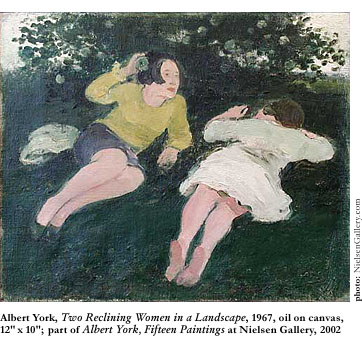

This side of the stairway landing is also where hang two more curious narrative paintings that make blatant use of symbols with archetypal meaning of Biblical and classical culture. York explores allegorical territory in the painting of Two Reclining Women in a Landscape—one of the few paintings in the show to betray the era of its creation. Painted in the 1960s, this canvas offers a secret look at the women relaxing in the grass in the luxuriant presence of a spreading apple tree. Dressed in knee-length skirts and blouses, they appear to be enjoying some good girl-talk on their lunch break from work. One woman, lying on her tummy with her shoes off and feeling the cool force of the earth against her length, folds her arms, rests her head on her hands, and faces her friend. Her friend props herself up on her elbow and looks across her friend, speaking from the heart into a more public distance beyond the picture frame. It would seem a quaint enough emulation of John Sloan, a slice-of-American-life painting from the Ashcan School, and bittersweet enough for that. But the apple the speaking woman holds to her temple—an icon of carnal knowledge as blatant as the stork—tells us what they’re talking about.

The New York art world, the one that gave rise to Pop art, Abstract Expressionism, and a few generations of conceptual art, is just a two-hour train ride from Albert York’s long-time home in the Hamptons. You’d never know it from Artist with Three Muses. This painting harkens back toward the Greeks, but stopping off with the muralists of John Singer Sargent’s time who did the public murals—frescos, maybe—in such places as the Boston Public Library and the Lincoln Memorial. Soft and otherworldly, it depicts a brush-bearing painter in plain brown vintage garb (a sweater and suit coat from the ’20s, say) out in the open on a summer afternoon. Planted squarely on the bare ground, he looks trustworthy and ardent, furrowing his sensible brow and gazing with his modest moustache into the symbolic distance located beyond the picture frame, somewhere behind us. If he’s a lonely, unpretentious painter who lives, as Joni Mitchell sang, “in a box of paints,” that must be why he’s lucky enough to be attended by the three muses—healthy, simple, wholesome, barefoot women properly attired for their profession in long gowns of faded cotton colors. They point his brush in the right direction, giving him perspective on what in this painting is a completely featureless dust-brown landscape; and they seem to have nothing better to do, no paintings of their own to work on. The primary muse on the right gestures across the subordinating forms of the other two muses to the painter in a trance on the left, throwing his whole being into a reverent appreciation of the beauty of the earth.

Admittedly, the simple girl with the premonitional stork, the office worker with the prophetic apple, and the idle muses with the inspired painter do not exactly further the cause of women’s rights or challenge traditional assumptions about the moral value of the imagery in Biblical and classical myth. But they do adapt those myths to plausibly modern settings, albeit quaint and bucolic ones, and that act in itself energizes the pictures.

Across the landing from this room, several more excellent paintings by Albert York—a similar mix of animal portraits, open-air landscapes, and allegorical narratives—awaits. It’s worth the wait, too. Red Roses in Glass Goblet. An Indian on Horseback and an Indian Standing by Water. Reclining Nude with Female Cat (after Manet’s Olympia). The paintings’ plainspoken titles speak for themselves, and for the painter—the kind who agonizes over his muted palette to say something quiet in concrete terms. It’s old-fashioned, figurative painting at its frumpy, substantial best.