If you’ve heard only one statement about Eugène Ionesco, it probably includes the word “absurdist.” In the three one-act plays of Ionesco, Not Ionesco, presented by Molasses Tank Productions at the Charlestown Working Theater, absurdity abounds: absurd situations, absurd dialogue, an absurd climax replete with shouting, dancing, singing, running in circles, and physical combat. So are they funny plays? Yes, and no. You will laugh; that much is virtually assured. You may also furrow your brow. Ionesco turns things inside out, trying to jar the audience into seeing what hides beneath the familiar surfaces of everyday small talk, family and business relationships, or scholarly phrases of theatre critics. In doing so, he creates ludicrous theatre that makes viewers laugh, yes, but also leaves them pondering, disoriented.

Ionesco stated in his book Notes and Counter Notes: Writings on the Theatre that the action of pure theatre is akin to the action of a sporting match—”live antagonism, dynamic conflict, the motiveless clash of opposing wills.” Therefore, expect not from Ionesco a typical drama with beginning, middle, and happy or tragic end! Each of the rarely performed plays chosen by director Steve Rotolo (who is also Molasses Tank’s artistic director) has its own flavor of dynamic conflict. “Improvisation (or, The Shepherd’s Chameleon)” shows Ionesco himself battling a chorus of critics; in “Salutations,” three gentlemen engage in an exchange of words at breakneck speed while onlookers judge; and in “The Picture,” a businessman cruelly dominates both his crippled sister and a young artist.

In “Improvisation (or, The Shepherd’s Chameleon),” Ionesco, played by Michael F. Walker, sits at his desk fidgeting and cowering as his scholarly critics march in one after another to badger him about progress on his latest play. Things go in circles, identical dialogue starting over each time a new critic enters. The pretentious “doctors” compete with each other to intentionally obfuscate by stating simplistic truths (“Plays are written to be performed. In front of an audience.”) as if profound, in the vein of philosopher Jacques Derrida. They argue about such things as the correct form of “vice versa” and whether Shakespeare was Polish before deciding they must “cure” Ionesco and his surroundings—fussing with his apparel, hanging placards indicating “fake” on the furniture, and the like. When the debate reaches its peak of ridiculousness, and the playwright has gone from rubbing his temples in distress to dancing about with a dunce cap on, the cleaning woman, played by Jane Martin, finally gets in the door and interjects a voice of reason before chasing the critics about with her broom.

In “Improvisation (or, The Shepherd’s Chameleon),” Ionesco, played by Michael F. Walker, sits at his desk fidgeting and cowering as his scholarly critics march in one after another to badger him about progress on his latest play. Things go in circles, identical dialogue starting over each time a new critic enters. The pretentious “doctors” compete with each other to intentionally obfuscate by stating simplistic truths (“Plays are written to be performed. In front of an audience.”) as if profound, in the vein of philosopher Jacques Derrida. They argue about such things as the correct form of “vice versa” and whether Shakespeare was Polish before deciding they must “cure” Ionesco and his surroundings—fussing with his apparel, hanging placards indicating “fake” on the furniture, and the like. When the debate reaches its peak of ridiculousness, and the playwright has gone from rubbing his temples in distress to dancing about with a dunce cap on, the cleaning woman, played by Jane Martin, finally gets in the door and interjects a voice of reason before chasing the critics about with her broom.

John Morton, Jason Beals, and Lara B. Krepps as the three critics (all called Bartholomeus) are right on time with their condescending lines, speaking in quick succession or shouting over one another or switching to sudden unison. With the exception of the broom-chasing melee, when I could no longer discern any of the lines, all three are sharp and clear, with good physical timing. Walker plays Ionesco as nervous and defensive, looking as if he doesn’t fit in his chair, legs skewed awkwardly. He rises to the comic moments, looking appropriately brainwashed and dancing about like a puppet. But he seems a bit too addled and surprisingly mild (there’s a Mister Rogers feel about his cardigan sweater) when he finally has his moment in the spotlight. Whether through directorial interpretation or the playwright’s actual intent to emphasize his plight as a victim of arbitrary and fatuous criticism, Ionesco comes off as weaker than one would expect.

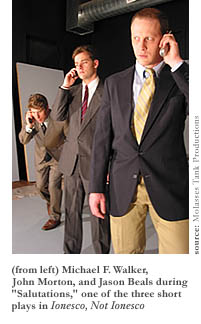

In the quick and lively “Salutations,” Beals, Morton, and Walker dominate the stage, firing a volley of non-sequiturs in response to an everyday question. “Gentlemen, how are things going?” it starts, innocently enough. “Nicely, and you?” “Warmly, and you?” they respond, and then “agnostically,” “amphibiously,” “melancholily,” and so on. They mimic standing subway passengers; they circle the stage furiously with cell phones. This linguistic lark parodies the hollowness of everyday social chitchat and also makes fun of itself, with Krepps and Martin playing spectators who peek in through windows and provide opposing commentary on the merits of the gentlemen’s exchange. The women in the cast don’t get much of an opportunity here, but the men rise to the considerable challenge of memorization and rapid-fire delivery. And the car-horn version of the tune “New York, New York” is simply hilarious.

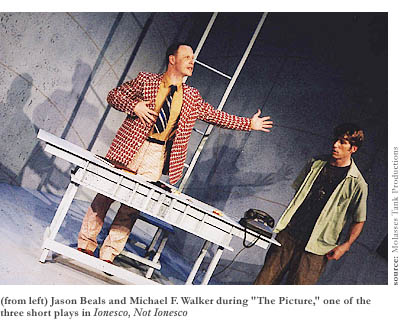

“The Picture” comes closest to a linear storyline and serves up the most complex character in the businessman, played with chilling fierceness by Beals. He drives a cruel bargain with a hapless painter (Walker) wherein the artist lowers his price so far that he agrees to pay the man to take the painting off his hands. Walker is better cast here as the pitiable painter, playing him with resigned deference and slack shoulders as he is forced to stand at length with his rolled-up canvas while the businessman soliloquizes. “I don’t in any way look down on artists” the man insists with pride, and periodically urges the painter to sit down—though there’s no chair for him. The businessman waxes on about his successes in the stock market and how he feels about art and artists (“I have the soul of an artist”), punctuating his words, often to brilliant comic effect, with a set of tiny toys on a desk. His professed struggle to find beauty is thwarted by life with his sister Alice, who is, he explains, ugly. The sister (Krepps) eventually hobbles in, and yes indeed, she is ugly—haggard, stooped, with awful glasses, one arm missing, the other cradling a cane—but not one-dimensional. Alice is a contradictory character. At first she furnishes unexpectedly astute observations about the painting, but later derides her brother for acquiring such filth and accuses him bitterly of paying attention to the woman in the painting instead of her. The power balance in the sibling relationship goes back and forth until eventually the businessman takes a drastic action that transforms them both, as well as the painter and an elderly neighbor (Martin). Krepps may overplay Alice a bit at first, but is stronger later when Alice does another turnaround and sobbingly begs her brother to spare her life, and at the end when she displays a transcendent calm.

“The Picture” comes closest to a linear storyline and serves up the most complex character in the businessman, played with chilling fierceness by Beals. He drives a cruel bargain with a hapless painter (Walker) wherein the artist lowers his price so far that he agrees to pay the man to take the painting off his hands. Walker is better cast here as the pitiable painter, playing him with resigned deference and slack shoulders as he is forced to stand at length with his rolled-up canvas while the businessman soliloquizes. “I don’t in any way look down on artists” the man insists with pride, and periodically urges the painter to sit down—though there’s no chair for him. The businessman waxes on about his successes in the stock market and how he feels about art and artists (“I have the soul of an artist”), punctuating his words, often to brilliant comic effect, with a set of tiny toys on a desk. His professed struggle to find beauty is thwarted by life with his sister Alice, who is, he explains, ugly. The sister (Krepps) eventually hobbles in, and yes indeed, she is ugly—haggard, stooped, with awful glasses, one arm missing, the other cradling a cane—but not one-dimensional. Alice is a contradictory character. At first she furnishes unexpectedly astute observations about the painting, but later derides her brother for acquiring such filth and accuses him bitterly of paying attention to the woman in the painting instead of her. The power balance in the sibling relationship goes back and forth until eventually the businessman takes a drastic action that transforms them both, as well as the painter and an elderly neighbor (Martin). Krepps may overplay Alice a bit at first, but is stronger later when Alice does another turnaround and sobbingly begs her brother to spare her life, and at the end when she displays a transcendent calm.

Beals plays the demanding businessman role with unflagging energy and verbal dexterity, switching nimbly from fierce and almost vicious declarations to a light, primly spoken “Well anyway, we’ll see.” His expressive hands are always in motion—tapping, clasping, pounding, pointing, tinkering, and gesturing with the toys. In the conversation with the artist he flashes a great big cold-as-ice grin and a raised-eyebrows-and-squinting-eyes look of utter condescension. Later he turns exuberant and giddy (“I’m in flower!”), talking lovingly to the painting and dancing euphorically.

“The Picture” could easily be done with total silliness, but this production instead has a complexion of seriousness, allowing the businessman to show hints of real passion and vulnerability, and Alice to display a range of emotions. It shows the ugly power differential between controlling man and dependent woman and between rich man and poor artist. The mysterious painting itself, bathed in a rosy glow, is made to seem magic, as if it really could transform a mean and bitter heart—even though we never see an image on the canvas.

The design and technical choices are effective throughout the three plays, especially for “The Picture.” The toys on the businessman’s desk are clever—brilliant, really—and the decision to hang the translucent “canvas” in front, so that the audience looks through it, works beautifully. Lighting designer Jay Dubois succeeds in achieving a radiant glow around the painting and a sharp flash of light for a gunshot.

All of these plays were written approximately 50 years ago, but Ionesco’s works don’t appear at all irrelevant—their fundamental messages are not explicitly tied to the era of their creation. They reveal no preoccupation with 1950s French society or politics, but rather—as good theatre should—with the perpetual human condition. And these are not comedies in the classic style, where disarray gives way to happy order at the end, nor are they traditional tragedies, where great heroes are brought low. Rather, in Ionesco’s plays each moment is comic and tragic at the same time. We may notice only the surface absurdity at first, but the heart-wrenching seeps through in due time. As Ionesco put it, “We laugh so as not to cry.”