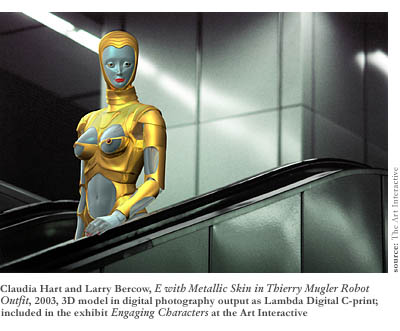

Who is that sexy if mechanical ice-goddess staring past you (and not catching your lecherous eye) from the escalator in the poster, her blue breasts, tummy, and face highlighted by her gold arms, neck, and ribs? Her alert red nipples and brilliant red lips seem to be made of metal, and her gaze is as chill as that of la belle dame sans merci. It’s not Jane Fonda in Barbarella, is it, or a creature from The Matrix or the Star Drek gene pool? No—and she’s probably not a cybernetic sexual object meant to lure hunky horn-dogs and lipstick lesbians into Engaging Characters, an exhibit of interactive art at the Art Interactive on Bishop Allen Drive in Central Square, Cambridge, through October 5th, either. At least not consciously. She’s on her way down the escalator, headed toward the electronics area of a department store, instead of on her way up to any higher level of consciousness.

Buzzed in the back door of the building that houses Cambridge Savings Bank and Cambridge Community Television (CCTV), you enter the business-like lobby, then the spacious gallery, and immediately you know it. It’s loud as hell, and it’s likely to be hard to stand in front of any particular piece in the exhibit and concentrate on it for the overheard sound of the sonics produced by other particular pieces. The noise surrounds you like it would at the androgynous dance club around the corner where each room blares a deafening decibel of house, industrial, or techno. In their separate cubbies, the installation pieces seem to be interacting with one another as much as they do with the gallery-goers, giving the name of the gallery an unintended (one would hope) meaning. You see that right away, and you haven’t even settled in yet.

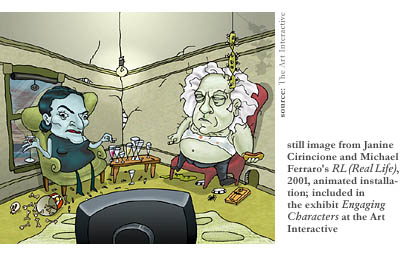

Stand, for example, in the doorless, black cubicle where Janine Cirincione and Michael Ferraro’s RL (Real Life) awaits you. See, on a small monitor, the animated depiction of a sedentary, working-class couple, maybe members of the lumpenproletariat, watching television and carrying on a banal conversation in the living room of their tenement apartment? For the wailing and moaning that echoes off the ceiling from some more bizarre cubicle or open-space wall across the large room, you can hardly follow their conversation—and you can’t tell whether they’re responding to you somehow, accelerating or slowing the pace of their conversation according to their awareness of your presence. You can see them chain smoke, sip martinis, and eat hot dogs, and you hear snippets of their banter about unpaid phone bills and broken cars between subconscious-sounding emanations from afar. “What the hell’s wrong with you?” the white-haired character with beer belly protruding from white t-shirt says. “It calms my nerves,” replies the tawdry wife—but you don’t know what the antecedent of “it” is. The martini maybe? The colored graphics of the cartoon are great—bare light bulb, cracked plaster wall, gray window blind, green window frames, with the mouse-trap, yellow fly-strip, and spilled bucket of chicken bones doing the stereotypical signifying that satire relies on. All quite skillfully rendered, too. But it’s too hard to follow the conversation with all the cacophony—and almost too distracting to tell that the woman’s accent in the cartoon seems a tad off, more like that of an actress attempting to pass as working-class than the real (albeit imagined) item.

You walk next door to find that the wailing isn’t coming from that adjacent cubicle. No noise, in fact, emanates from Claudia Hart and Larry Bercow’s four digitally mastered photos of models in actual (or presumably actual) public environments. They have fashion-trendy titles—E Without Nose or Mouth in Comme des Garçons Coat, for example, and E with Spherical Nose in Paco Rabanne Transparent Dress—and they’re what ordinary folks might call “weird to look at,” which could be good or bad. But the absence of sound—can’t the robots talk, for crying out loud?—makes them more eerie than they might already be, especially embedded in the cacophony. In one photo collage, in the flesh and garb of an African-American model, the robotic E—a mutable icon who dons and doffs identities like so many mini-dresses—stands outside of the chic boutique that a handsome young black man (a real man, not a cybermutt) glances from, her image duplicated in a mirror somehow. It shouldn’t necessarily call—and you really wish it wouldn’t—the bloodless genre of science fiction to mind; but it does, in all its sanitized glory.

In another photo, a lighter-skinned incarnation of E (as seen in the poster out front) walks our way down a rainy street in a sidewalk crowd of flesh-and-blood people who don’t notice that a robot walks among them (they must be compartment-minded Bostonians, at best indifferent to strangers)—her orange-dotted green transparent dress revealing a lovely, muscular, if completely technological body.

Those two E’s are complemented by two others—a yellow-and-gray version of the yellow-and-blue robot on the escalator in the poster and a freaky, doll-baby version in a billowing red miniskirt, calf-high ivory boots, and a red Mohawk looking our way with vacuous, electronic eyes from a spotless passageway in what would appear from the signage to be a German subway station. Might it be a comment, as dated as comments get but still worth hearing, on the mechanical content of fashion—a suggestion that people who adhere too closely to fashion trends dehumanize themselves and become robotic? No, not on your life. Too literal a reading. Surely there’s something more semiotic going on in this iconographic—a scholarly, gender-bending, post-feminist text you’re unable with your crude ink pen to unpack. But what makes the enigmatic E interactive? She’s not interested in the other beings in her environment, much less in you. She’s a solitary swinger in the cool, sparkling metropolis.

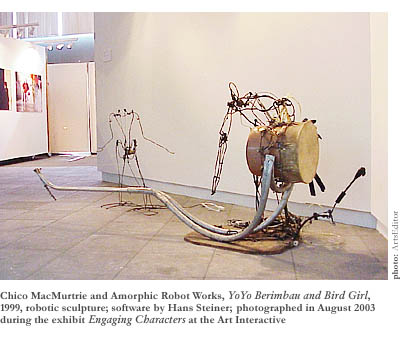

Between the proletariat parody and the remotely ambiguous presentation of four female robotic types, you wonder where you’ll find yourself next—maybe in a kickboxing match with a robot? A couple of robotic sculptures are on hand to greet you after all, and the helpful, very human gallery attendant is happy to introduce you to them. Created with elaborate software and wads of inscrutable wire worthy of the movie Brazil, these machines made by Chico MacMurtrie and Amorphic Robot Works make an awful lot of racket. One wiry robot dances spastically on command while the other engages with an object in the shape of a sled, which trembles fearfully on the floor. Ever since you saw Charlie Chaplin get swallowed by a machine in Modern Times, you’ve leaned toward the Luddite, even if Martin Scorcese did say the robot Hal from 2001 was a great character.

But you can walk toward the small screen set in a nearby freestanding rectangular column and get a better sense of the interactive possibilities of the exhibit. There’s still too much ambient noise to make it easy to appreciate fully, but the sound is easy to assimilate in this one. That’s because it consists of grunts and groans, mostly. A naked green animated character named Pussy Weevil, created by Marina Zurkow and Julian Bleecker, sees you coming. He—if such a thing merits a gender-specific pronoun—quits his foolish noise-making and his acrobatics against an orangeish flat background and exits stage right, or dives mysteriously into the deep orange with a cool little splash, or balls himself up into a seamless green droplet, and disappears, hightailing it away from you, only to emerge a moment later amidst a lot of goofy noise (guttural now, shrill next time) with his big black eyes and infantile nakedness, perhaps leaning over to moon you grotesquely, then leaving behind his green foot in a leap out of the screen. Chest-thumping to intimidate the viewer that he’s been electronically programmed to sense in his presence, mocking the two parts of a conversation he’s been programmed to overhear in front of him, he’s a behaviorist’s project, and he’s a joy to interact with—the little creep. He could be programmed to do anything. His creators chose to program him to make fun of viewers and be a little pain-in-the-ass libido on legs because…well, because that’s the sort of bratty mood the kids are in these days.

What, you are led to wonder by this exhibit, might be the competitive credo of the disaffected art-school crowd who create such cybernetic pieces? The experimental/experiential stuff can be funny, yes, and interactive as well; but why is “interactive” necessarily good? Does the onlooker have to engage the character in a work of art in order to be changed by it? Is it a virtue in itself (and not mainly a thing the spoiled children of the Joneses have to have in order to keep up with each other) to be master of these machines? Is emotional range forsaken in the pursuit of intellectual range?

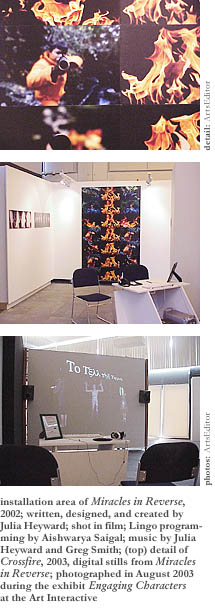

Happily, another clearly interactive piece, Miracles in Reverse by Julia Heyward, convinces you that there’s something to this exhibit beyond cleverness and super-cool satire. It’s a click-and-drag show. Sit at the station and click the mouse on any of the three images—on the back of the cloaked figure, the back of the shaved head, or the back of the girl in the red dress. In that order, you’ll be offered the opportunity to guide the movement of the cloaked figure across an expansive snow field that’s populated by other figures almost as enigmatic as he; to activate a veritable chorus-line of sexless identical figures (pallid pod-people perhaps?), at every sixth or so an actual woman extending to you a capsule (your medicine’s ready, o mad one at the keyboard) to help settle your nerves; and to swing the little girl around with your hands in a circle as she laughs carefreely and delightedly as if you were her parent. Click, click, click—you do it all day at work, and now it’s the weekend and you’re doing it at play—click on the corresponding image and watch the arrangement of figures on the snow field cross and re-cross the white slope on a gray day, the line of nude clones go by with their pill-happy attendant, the little girl swing around and around. And listen to the insane, very possibly inane sound effects meant to drive you mad with their dissonant juxtaposition to the visual imagery and not with their cacophonous interaction with the other pieces in the exhibit.

Happily, another clearly interactive piece, Miracles in Reverse by Julia Heyward, convinces you that there’s something to this exhibit beyond cleverness and super-cool satire. It’s a click-and-drag show. Sit at the station and click the mouse on any of the three images—on the back of the cloaked figure, the back of the shaved head, or the back of the girl in the red dress. In that order, you’ll be offered the opportunity to guide the movement of the cloaked figure across an expansive snow field that’s populated by other figures almost as enigmatic as he; to activate a veritable chorus-line of sexless identical figures (pallid pod-people perhaps?), at every sixth or so an actual woman extending to you a capsule (your medicine’s ready, o mad one at the keyboard) to help settle your nerves; and to swing the little girl around with your hands in a circle as she laughs carefreely and delightedly as if you were her parent. Click, click, click—you do it all day at work, and now it’s the weekend and you’re doing it at play—click on the corresponding image and watch the arrangement of figures on the snow field cross and re-cross the white slope on a gray day, the line of nude clones go by with their pill-happy attendant, the little girl swing around and around. And listen to the insane, very possibly inane sound effects meant to drive you mad with their dissonant juxtaposition to the visual imagery and not with their cacophonous interaction with the other pieces in the exhibit.

You can still hear the working-class animated couple bicker through their bitter script in their tenement from the RL (Real Life) piece on the other side of the gallery, compounding the dissonant juxtaposition of sound and visual imagery in Miracles in Reverse. (You can reverse the action—that’s why it’s called that.) But at least there’s a set of headphones here to block out some of that noise.

Fortunately, that’s also the case in Toni Dove’s Sally or The Bubble Burst, an interactive DVD-ROM that “uses speech recognition and synthesis to allow viewers to enter the world of Sally, an inhabitable responsive narrative character based on the 1930s fan and bubble dancer Sally Rand.” A sexually provocative tease, Sally could draw as many sexually hungry art-lovers as the Trekkie robot on the escalator—but she ought to draw some major-league techies, too. Look at the bizarre images on the screen that you can select. With a click of the mouse, put her face on the translucent surface of the bubble. With another click, let her do her burlesque, draping herself (the artist dressed as the sex doll) with her platinum hair-do and shapely legs across the bubble in her skimpy outfit. Make her say whatever comes to you, whether the William Blake lines about the soldier’s blood running in blood down palace walls or the road of excess leading to the palace of wisdom, or those Emily Dickinson lines about the emperor getting down from his chariot to kneel upon her mat at the gate of her Amherst home. Something you wouldn’t expect a fan and bubble dancer of the ’30s to say necessarily. But listen hard for her parroting of the lines, because that dissonance from the rest of the gallery is getting in the way.

The characters at the center of all the pieces on display at the Art Interactive are engaging to a degree. But the individual pieces need some soundproofing to attain their full potential—and even then, it may be that characterization ought to be left to fuddy-duddy literary fiction, traditional narrative painting, and dramatic theater.