He began his career deeply entrenched in the conventional exemplary work of deceased artists. But while the recognition and realization of art history is vital to the creation of art, Tom Friedman soon found himself dissatisfied with his Thomas Hart Benton-esque drawings and began to search for a new avenue of visual expression. While attending the University of Illinois in Chicago, Friedman emptied out his studio, boarded up the windows, painted the entire space white, and thus wiped the proverbial slate clean. It was this cleansing that was the catalyst for a new form of art that would make Friedman one of the more prominent living visual artists. Little by little, he would bring everyday household elements into his studio space and begin the process of creating artworks that were aesthetically pleasing as well as conceptually founded and culturally relevant. Many young artists often flounder and get lost in the gallery world never to escape, but after Friedman’s work was picked up by Feature, Inc., a gallery in New York City, the artist was able to transcend this intermediate state and garner exhibitions at the Museum of Modern Art (NY), the Art Institute of Chicago, and the New Museum of Contemporary Art (NY), among others.

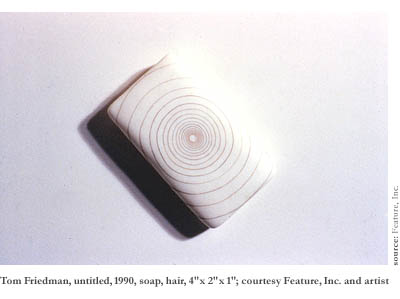

While many artists struggle with the balance of craft versus concept, Friedman seems to be able to dance effortlessly around the two, producing artwork that is visually intriguing as well as rich with underlying commentary. In one piece, he created a seemingly perfect concentric spiral out of a thin black line on a white bar of soap. Further inspection reveals that the black line is in fact the artist’s pubic hair, which has been painstakingly manipulated around the soap to create a perfect spiral. The audience may react to this in a couple of ways: they can be disgusted by the fact that they had gotten so close to pubic hair foreign to their own body, and were (for the time being) enjoying the sight, and/or they can become further intrigued by the meticulous craft involved in the placement of the pubic hair and hopefully arrive at some sort of ideological standpoint regarding the two contradicting elements in the piece. It is this latter reaction that can be a doorway for commentary regarding the conceptual elements involved in the piece, and where the aesthetic elements, as vital as they are, can be left behind.

While many artists struggle with the balance of craft versus concept, Friedman seems to be able to dance effortlessly around the two, producing artwork that is visually intriguing as well as rich with underlying commentary. In one piece, he created a seemingly perfect concentric spiral out of a thin black line on a white bar of soap. Further inspection reveals that the black line is in fact the artist’s pubic hair, which has been painstakingly manipulated around the soap to create a perfect spiral. The audience may react to this in a couple of ways: they can be disgusted by the fact that they had gotten so close to pubic hair foreign to their own body, and were (for the time being) enjoying the sight, and/or they can become further intrigued by the meticulous craft involved in the placement of the pubic hair and hopefully arrive at some sort of ideological standpoint regarding the two contradicting elements in the piece. It is this latter reaction that can be a doorway for commentary regarding the conceptual elements involved in the piece, and where the aesthetic elements, as vital as they are, can be left behind.

The white bar of soap represents a cultural cornerstone for cleansing and hygiene, which could also act as a metaphor for sanctification, embraced and/or beautifully strangled by a grown man’s black pubic hair. Not only are the two values (black and white) visual opposites, but the idea of something so human and sexual coming into contact with something so pure becomes vexing.

What further augments this artwork, and detaches it from a lot of the elite indoctrination that is often associated with “conceptual art,” is that it is created with a cultural vocabulary to which most everyone can relate. We have all seen the image of hair stuck to a bar of soap while in our showers, and just like when Marcel Duchamp placed the R. Mutt urinal in his exhibition, it is the transferal from the external world and into the gallery setting that gives way to a slew of discussions, such as the constant battle between cleanliness and inherent human interaction, the sanctity of privacy, or perhaps even the sanctity of fine art. In this one piece, Friedman has not only dealt with the concept of craft versus content and the notion of purity, but he has also dealt with the idea of art and impermanence. So often we hear in the art world about the importance of archival-quality materials in creation. Photographers, sculptors, and painters alike all make great attempts at having their work stand the test of time, but in Tom Friedman’s case, while all possible archival processes are implemented, the work sometimes necessitates a transient nature.

Another work that deals with the same balance of craft and concept is Friedman’s reproduction of a ruler from memory. Here, the artist uses an element in our culture that we refer to on a regular basis, one where the concrete and specific aspects of the object are that which validate its existence and necessity in our daily lives. However, Friedman refutes this idea of exactitude and creates, as precisely as humanly possible, a reproduction of our standard of measurement. Not only is he accessing information from his own memory to create this work, but he is again manipulating an icon from our own culture to which everyone can relate. The craft involved in creating a ruler from memory to look like a machine-made piece is impressive, but what furthers the work is the associative conceptual angle. Here, the artist deals with an almost John Henry-esque story of man versus machine. The only difference is that in the story of John Henry, who attempts to drive railroad spikes as fast as the machine, the competition involved speed, where this competition involves accuracy. This analogy extends itself to painters such as Vermeer and Titian, who were constantly trying to achieve photo-realistic paintings. In this case, the idea of man-made art versus machine-enhanced art is the same; just the competitor has shifted.

While some of Friedman’s work involves a specific, conclusive piece of artwork, some of the work leaves the idea of having a finished product behind, and focuses more on the process. Not unlike the artists Sol Lewitt and Jeff Koons, he has been able to take the artist’s hand completely out of the equation. One Friedman piece involves only one sheet of ordinary paper that was pinned to the studio wall. He then stared at the paper for 1,000 hours, thus completing the work. Inasmuch, while all the physical elements of the paper stayed exactly the same, the inherent value and history of that piece of paper was drastically changed by the process. Friedman took this concept a step further with his piece Untitled (A Curse). He was able to take any tangible element out of the work by simply placing a pedestal in a gallery space and then having a witch curse a 28-cm sphere of space just above it. While nothing was physically observable, that space was (or was not) completely altered, based on your belief in or skepticism of cast curses. With the aforementioned work comes a necessity for trust between the artist and audience. Friedman is playing with the notion of a “creation” that sees no physical fruition. The audience must trust that the artist has indeed created artwork. Works such as these not only redefine the artist and audience relationship, but also push the limits of what can be considered “creation.”

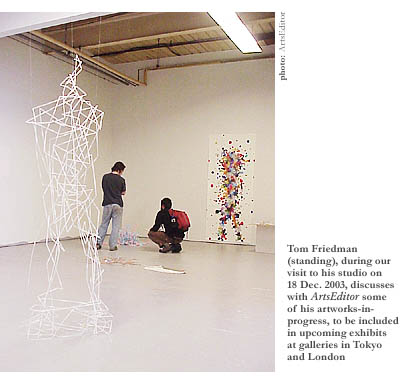

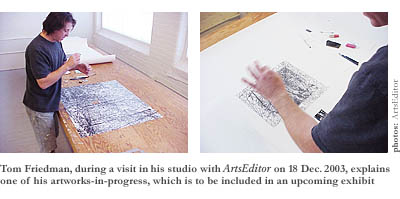

After meeting the artist in his Easthampton, Massachusetts studio space, it was clearly evident that his studio is still the birthing ground to a wealth of evolving ideas. Currently, Friedman is preparing a number of works for two upcoming exhibitions, the first of which will open in late March at the Tomio Koyama Gallery in Tokyo, Japan. One of the works for this exhibition is a larger-than-life sculpture of a urinating figure made completely out of clear standard drinking straws. While the piece was unfinished, the busyness of the connected straws still held a clear figural form while getting across the notion of the body as a vessel. All of the straws are connected by simply wedging the end of one straw into the end of another. However, one important aspect of the work is that the linear composition starts specifically at the top of the head, progresses through the entire body, and ends as the urine stream makes contact with the ground. When asked about this work, Friedman suggested that the piece was about the “idea of origins” and the thought that many ideas and thoughts enter the mind, are processed by the person, and are many times discarded just as easily as they were introduced.

Another unfinished piece during our studio visit in December that deals with the same concept of “origins” was a more conventional, two-dimensional work where Friedman used colored pencils, varying applied pressures and one-point perspective to suggest an infinite, concentric, receding space. While this work employs different art-making methods, the concept of something with a specific origin and the importance therein is vital to the work.

Friedman is also producing other two- and three-dimensional pieces for an exhibit this June at the Stephen Friedman Gallery in London, England. One of these pieces falls into a more conventional setting, while still maintaining a very specific Friedman-esque quality and attention to detail. With this piece, Friedman is creating a hyper-realistic drawing of trees, brush, and forest-related imagery, which is a reference to a specific scene that he passed on a recent drive. Even though the content consists of a forest scene, the composition and placement of the branches and flora develops an almost anatomical feeling of veins, arteries, and capillaries running through a body. While the work is composed solely of pencil on paper and seems to be a bit removed from some of the other pieces, the importance of minutiae and fine craftsmanship creates a certain interplay and relative dialogue among the rest of his recent works. When asked about this drawing’s subtle removal from what I had been expecting to see, Friedman suggested that it is very much aligned with the rest of his work, and it is the very idea of seeing the works together and having them contradict one another that gives them weight and a necessary opposing viewpoint.

When viewing Tom Friedman’s entire oeuvre, it is clearly evident that his artworks all seem to have a certain feel of modernity. Whether it is something that is relative to the life of Friedman himself, such as the forest scene he found on the side of a road in Massachusetts, or the immeasurable references to popular culture, it is an art that is very reflective of today.