I have never been especially fond of overtly political paintings—or people for that matter. There is something base about them, something contrived.

Former New Yorker art critic Harold Rosenberg said that the opinions of painters do not decide elections, and, as a political tool, painting in this century has been meaningless. Naturally! Painting is something altogether finer than oppression, deceit, gunpowder and fabrication. People with money and property have long felt it their God-given right to wield power over artists, which is something akin to slavery, and is the very reason I believe that as with the separation of church and state, so should it be with painting and politics.

The most noteworthy example of modern political painting is Picasso’s Guernica. While his genius and fecundity are unquestionable, a question remains: Did the painting ail the Fascists with whom it was at odds? Hardly. They wanted to acquire it. Or did it give rise to the people who suffered at the hands of their enemy? Perhaps, but only in recompense, for already the horrors had been committed. No, the single most effective political message Picasso ever sent was not in Guernica or in any other of his works, it was when he left his homeland to live in France.

Throughout history artists have been thought of as second class citizens and serfs. If history has taught us anything, it is that those involved with politics in one way or another fall prey to the nature of its conceit.

New York artist, international instructor and lecturer, Bruce Dorfman, feels that politics suggest negotiation, and subject an artist to innuendo. In the 1950s, he was approved for a Fulbright grant, but because he was friends with a man who at the time was on Joseph McCarthy’s red list, Mr. Dorfman’s funding was canceled. Despite the government’s despicable behavior, he persevered and is among the finest contemporary artists alive.

“As an artist, I don’t make a conceit that I need other people’s money to create,” he said. “I can do whatever I want. An artist will do what they need to do to get something to work. But Art, with a capital A, just happens. It may be beautiful or it may be ugly. But it does not negotiate.”

Unfortunately, those in power do negotiate. They live for it, their eyes ablaze with dollar signs. They thrive on it. And when an artist is involved with public policy, the intangible circumstances of bureaucracy inevitably cause delay, secrecy and misunderstanding.

The early commissars, whether they were of a religious deputation or a governmental one, rarely allowed artists to even sign their own work. And what of the NEA? It is a calamity wrought with decades of cronyism. The decisions on which artists receive endowments are all made on a purely political level; nevermind the artists’ merit. Politics prove that in order to “succeed” in the arts, it’s not what you know, it’s who you know—one of art’s tragedies.

By now most people know the story of Diego Rivera’s coronation by Rockefeller, and his work’s subsequent destruction due to

its overtly political content. There is an extent in art that is successful when it speaks in a singular expression which leads to

revolution, but Goya and Rivera, i.e., attempted to elevate political gestures or scandals and then rode the popularity in the name

of revolution. Nobody questioned those artists’ abundance of passion or talent. But why should painting cease to be the pursuit

of beauty to instead become a reactionary recording of history?

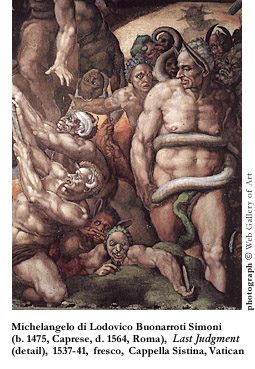

A Michelangelo mosaic in the Vatican in Rome, of Minos, the Judge of the Underworld, depicts a snake ascending the leg of Biagio da Cesena, the Pope’s Master of Ceremonies, with whom the artist had had many public disagreements. The artist likened Minos to Biagio, and the snake’s teeth are sunk to the gums in Biagio’s johnson—a vengeful and spirited act against Biagio’s publicly insisting that Michelangelo’s work “was a most dishonest act in such a respectable place to have painted so many naked figures immodestly revealing their shameful parts… it was not a work for a papal chapel but for a bathhouse or house of ill-fame.” Equally ridiculous is the recent discovery through renovation that that particular painting, and many others besides, had been covered over because some bishop/politician or other disapproved of them.

A Michelangelo mosaic in the Vatican in Rome, of Minos, the Judge of the Underworld, depicts a snake ascending the leg of Biagio da Cesena, the Pope’s Master of Ceremonies, with whom the artist had had many public disagreements. The artist likened Minos to Biagio, and the snake’s teeth are sunk to the gums in Biagio’s johnson—a vengeful and spirited act against Biagio’s publicly insisting that Michelangelo’s work “was a most dishonest act in such a respectable place to have painted so many naked figures immodestly revealing their shameful parts… it was not a work for a papal chapel but for a bathhouse or house of ill-fame.” Equally ridiculous is the recent discovery through renovation that that particular painting, and many others besides, had been covered over because some bishop/politician or other disapproved of them.

An artist’s original expression? An artist’s opinion? Blasphemy!

Bullfighters speak of their Duende—the deep rooted dignity and spirit of their artform. They pride in the extraordinary stillness in the moment before the fight, and the blaze of color and light during it, where a deeper sense of nature springs forth. It is visceral and everlasting, albeit violent, and is but one source of true inspiration.

New York artist SICA blends excerpts in her paintings from the 11th Century Chinese poet Su Tung-Po to create the idea of space,

or in SICA’s words, “the absence of objects.” Space is the essence of immortality, and politics its antithesis.

With the news that 70 artists—Elizabeth Murray, Yoko Ono and Frank Stella, i.e.—donated their works to benefit Hillary Clinton’s Senatorial bid, one may get the sense that artists do indeed make a difference at the polls, or at least try to. What is more likely, though, is that these artists are simply stating their disapproval over a mayor’s tiff with a museum’s exhibition. I hardly believe that a politician’s campaign is what inspires an artist to paint. Now, what once was art is merely cold cash fueling the rhetoric machine.

I do acknowledge that regardless of its effects, political consciousness is necessary for an artist in order to view the world objectively. However, because politics inspires deception for the sake of domination and power, artists must distance themselves from such dealings, for it is perfectly conceivable that a religion, corporation or government could be commissioned to adhere its system to the artist’s aesthetic, rather than the other way around. If ever the notion of a cultural revolution were to take place, this reversal of history, instigated and realized through the arts, would be intrinsic to the realization of true beauty and freedom.

Cultural Mirror is a featured section of ArtsEditor. “Paint and Politics” also appears in our Annual Print Issue 2000.