The clean-cut Methodist history buffs from Ohio, done investigating the Old North Church and Copp’s Hill Burying Ground, have gone away—to Legal Sea Foods in Park Square, probably, or the J. August all Harvard all the time souvenir shop in Cambridge. The North End is hopping once more with secular hedonists and lapsed agnostics in the early evening of a long summer day.

Locals and tourists drink iced espresso concoctions and nibble at biscotti and cannoli in the windows of open-air cafes on Hanover Street. Comely maidens with cover-girl faces greet customers at the doors of side-street trattorias, navels studded with silver, bronzed midriffs and golden calves waxed, menus clutched in polished hands. Hungry bruisers from the loading docks of Chelsea produce warehouses, the boardrooms of State Street investment firms, and the frat houses of Boston College move in herds toward the huge helpings of pasta to be had at La Famiglia Giorgio on Salem Street. Everywhere, couples cuddle and whisper at tiny tables amidst plaster reproductions of Venetian porticos and genuine imitations of Pompeiian murals.

Paul Revere’s old wooden house on North Street, nothing about it even remotely Italian, is closed for the night. Dozens of groomed pedestrians continue to pass it, in triangular, cobblestoned North Square, on the way to Prince Street eateries. Some, though not that many, of the more observant pedestrians notice that Crosstown Art, an elegantly renovated first-floor gallery that has retained the tin ceiling, is open for business, and that it welcomes perfect strangers to its latest exhibit—DreamSicles, A Summer Treat—on display through August 31st.

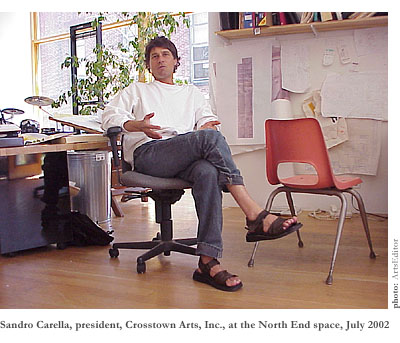

Sandro Carella, the handsome and hip North End native son who spent three years fixing up the space prior to its 1999 opening, thinks he knows why more of the tourists don’t dare to venture into his gallery. It’s not because they’ve already been to the higher-end, long-established galleries on Newbury Street, either. “I doubt that a lot of the people who come to the North End understand what the Paul Revere house is all about,” he says. “So what are they going to say about the artwork they see here?”

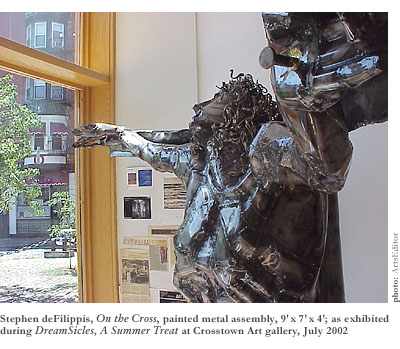

It’s probably true that a certified middle-American from some anonymous maze of shopping malls and housing tracts would be hard-pressed to make sense of Carella’s Crosstown Art. A citizen weaned on video games and cable TV might wonder what that extravagant metal statue of the crucified Jesus is doing in the large front plate-glass window of that finely refurbished commercial space over there on the corner, for example. (Is that a statue of David Bowie, or do they sell religious artifacts for parishioners from the Sacred Heart next door?) It’s a respectful enough rendering of the most readily recognizable icon in the entire Western world, after all. (Still—the tourist might wonder—why is the nine-foot Jesus parked in the window, like the doggy in the jingle, practically at eye level? Isn’t that for some vague reason wrong?)

Not everybody out to down a plate of linguini alfredo on Prince Street is a total dope. Given a minute, almost anyone would want to wander over to take a closer look and see that the statue has been assembled of metal parts (recovered from auto bodies, as it happens) welded together, and that the seams between the painted silver sections resemble stitches in flesh. (So it’s not a religious artifacts store—it’s an art gallery, and this is Stephen deFilippis’ erotically agonized On the Cross.) Angular silver face contorted by pain, silver strings of metal hair curling down his neck, deFilippis’ Jesus hangs on the silver cross in plain view of a gray, mold-formed cement Christ that looks down on North Square’s sinners from the heights above the entrance of the nearby Sacred Heart, projecting by virtue of its proximity at street-level a more personal expression of our collective frailties than the mass-produced icon.

If On the Cross isn’t enough to beckon the passerby inside, then maybe the rocks in the other large window that flanks the door are. There’s nothing remotely controversial about the small, smooth river stones that William P. Reimann has fished from Maine currents and etched with symmetrical patterns, some like exploding nebulae, others like starfish or urchins, all of them as unique as snowflakes. Reimann, a widely commissioned public-works artist whose ornamental, sometimes representational stone reliefs can be seen in Boston-area parks, draws the image onto the already beautiful rock (always one small enough to hold in the hand) and, protecting the surface areas of the stone that are not to be engraved, sandblasts the grooves into the river stones. This happens at a monument-maker’s facility in Scituate—perhaps where they pour cement forms of Jesus. A dozen or two results of Reimann’s diligent draftsmanship and manual labor play an inconspicuously powerful part in the DreamSicles exhibit, along with a large, two-dimensional engraving of a butterfly in a square of slate. His work isn’t particularly “dreamy,” per se, and it wouldn’t put many in mind of popsicles. It’s hard and impersonal—finished work of an earnest craftsman—and a privilege to handle and to see.

Curator and gallery owner, Sandro Carella favors artists like deFilippis and Reimann—the kind, he says, who “would perish if they couldn’t do their work,” and whose work is “unmistakably that artist’s and that artist’s alone.” Carella has particular admiration for the 70ish Reimann, who he feels is under-appreciated, and has a personal as well as a professional admiration for him. “Reimann taught me how to draw when I was a student at Harvard,” says Carella, who studied economics in the late ’70s and early ’80s and later ran the art department of a computer games outfit.

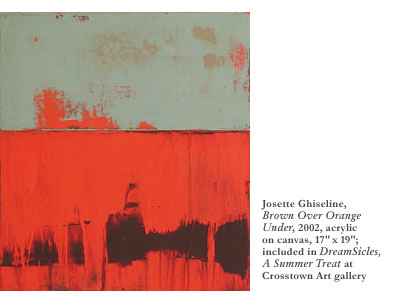

Carella finds artistic integrity in the work of Josette Ghiseline, too. She’s a painter, mainly. Her portfolio includes images of some impressive abstract work that looks like color-field painting with texture and depth. One of those works—Brown Over Orange Under—is on display in this exhibit, along with a sextet of mixed-media pieces made of “paint and photo transfer on Arches paper.” The mixed-media pictures may not be as affecting as the acrylic paintings that Carella represents for Ghiseline—the golden smudge swirls somewhat frivolously over a sepia photo of an ancient tenement’s façade in Rome; and the grainy old photo of the capital letters AURA (from the sign of the now-defunct European RestAURAnt on Hanover Street, according to Carella) might not gain that much in resonance and association from the zig-zag slash of color it wears. The swirls and slashes seem sort of gratuitous. But Brown Over Orange Under and the other acrylics in Carella’s stock—Seven Sentences and Empathetic Transference among them—are great. “She glorifies what nature decays,” says Carella of the representational abstractions.

Trouble is, with six artists, there isn’t room to exhibit more than a small sample of anyone’s work—and that’s a problem generally with the too-cheerily-named DreamSicles, A Summer Treat exhibit. Once the passerby has ventured inside, he or she is likely to have a hard time negotiating the space and paying full attention to any one piece. At the entrance it’s great to see (for reasons of cultural authenticity) that the stairs descend to Carella’s mother’s seamstress shop—Maria Dressmaker—but disconcerting to notice, on wandering deeper into the gallery, that office machinery and furniture gets in the way, drawing attention away from the artwork.

A laser printer on wheels blocks the way to a closer-up encounter with the crucified Jesus. A five-foot-long Hewlett-Packard photocopier (for reproducing the architectural, freelance drawings with which Carella makes ends meet) blocks the approach to the white wall where Reimann’s slate butterfly carving has been mounted. Designer chairs line the wall where Ghiseline’s work hangs. And most of Reimann’s gathering of Maine stones lines a window sill that is somewhat obscured by Carella’s mid-gallery office space on one side and his Crosstown rock band’s instruments on the other.

So it takes a little more effort than one might wish to appreciate the work of deFilippis, Reimann, and Ghiseline, and of Megan McNaught and the Inglis twins as well. McNaught, like the rest of the artists in DreamSicles, is a repeat participant in Crosstown’s exhibitions. She has two acrylic paintings on the wall back near the drum set and amps. Simply titled Words and Drawings, they exercise the optical nerves and entertain the associative faculties—and send one, later, to Crosstown’s thorough Web site for a look at a fuller range of the artist’s successful experiments in colorful, geometric pattern-making.

The Inglis twins are easy to tell apart by their divergent artwork if not by their nearly identical grinning visages and similarly personable presences. Peter does the small, hand-sized sculptures of figures that, suggested by the modeling of just their essential forms and not articulated in great detail, create quietly lonely atmospheres. Lingering nearby, the viewer feels a little sorry for the bronze Sleeping Man lying on his back with hands behind his head and one ankle crossed over the other. (He seems to be the only piece actively supporting the DreamSicles title.) Forming a trinity with Solitary Figure and Full Figure, these tiny statues serve as homely and sympathetic counterpoint to the dramatic ostentation of the Christ in the window.

Paul does the small oil paintings of recognizable Boston settings—a Park Street subway entrance and a Copp’s Hill Burying Ground scene, for example, neither of which could be accommodated in the exhibit—and he also did the ingenious three-dimensional study of light and color titled A Place on the Water. Occupying a discrete slice of gallery wall, this piece consists of nine three-story window frames projected at a perpendicular angle to the wall, each set of three frames painted an ivory white on the front and a different color on the back that in turn blushes the facing window frame a respectively warm or cool aqua, mustard, lime, or dark pink color.

Paul Inglis’ three-story windows may put one in mind of a densely populated neighborhood like the North End. The windows in the North End tend to be tarnished green copper, though—or did before the neighborhood’s gentrification of the past two decades. They are never as neat and clean as those in Inglis’ architectural model, and they still sometimes have people sitting in them. Not usually the kind of people who’d go to Carella’s Crosstown Art maybe. But people who probably know Sandro and his mother, Maria Dressmaker, by name.