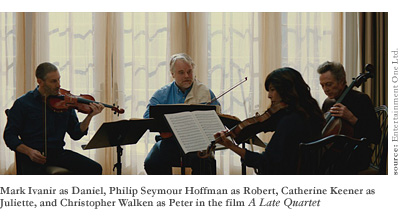

At the start of the film A Late Quartet, members of The Fugue—Daniel, Peter, Juliette, and Robert—walk across a brilliantly lit stage. The crowd holds its applause as the musicians take their seats. Cradling their stringed instruments, the members look at each other in congratulations for celebrating a rewarding twenty-five years together. In a graceful turn of her head, violist Juliette (Catherine Keener) nods to the esteemed cellist and music teacher Peter Mitchell (Christopher Walken), as if to signal the beginning of their performance. Yet, calm and subdued, her glance could quickly be taken for that of pardon, perhaps even consolation. For this ambiguity, we owe our full attention.

A Late Quartet, directed by Yaron Zilberman, would have us first think that a film story, much like a great piece of classical music, moves with purpose. Musical bars become scenes; momentum builds to narrative crescendos; passages lead to resolves. And while the film does certainly assimilate some aspects of this musical scaffolding, Zilberman and co-writer Seth Grossman chose a peculiar piece in which to have the story enveloped—Beethoven’s quartet (Opus 131) in C sharp minor. It is this piece, we soon discover, that The Fugue has practiced relentlessly for their performance at the beginning of the film. It is this piece that haunts the film’s soundtrack periodically. It is also this piece, as Peter informs his students, that was so novel at the time of its creation because Beethoven wrote it in seven movements, as opposed to the traditional four. So then, if we were to continue with the analogy between what is thought to be conventional narrative and classical music structure, we may find a pleasant discord. We bear witness to the imminent dissolution of The Fugue and the odd, creative dynamic of its members as two distinct thematic categories emerge—old vs. new, tradition vs. change.

When the ever-eloquent Peter discovers that his time performing with the quartet on stage will soon come to an end with the onset of Parkinson’s disease, Daniel, Robert, and Juliette are stricken with the utmost conflict in seeing their friend transition out of lifelong musicianship and into compromised health. However, Peter placidly absorbs the predicament, taking it for what it is. His calm demeanor, which makes it appear easy for him to advise the remaining members to continue playing, is only echoed in the life he leads as a widower in a historic Manhattan penthouse apartment. Yet, as only an aging Christopher Walken’s eyes could suggest, Peter is on the verge of an emotional break, and it could not be more apparent than when he attends a therapy session for others suffering from Parkinson’s. As the instructor tells of the muscular restriction caused by the disease, she states “everything gets smaller”, from posture to gait. For Peter, as he vapidly watches others stretch their arms and hands out in what the instructor calls practicing “conscious movement” to improve muscular mobility, nothing could be more challenging to a seasoned cellist’s dexterity or occupation.

To move consciously—something with which the remaining members of The Fugue will have to cope. Aware of a potential disbanding, Robert (Philip Seymour Hoffman), the second violinist, suggests “alternating chairs” with Daniel (Mark Ivanir), the first. As the film progresses, we learn just how significant Robert’s dissatisfaction with his role in the quartet is, despite his confession that the positions of a quartet’s two violinists should never be considered “hierarchical”. Always the provocateur, the one willing to take risks when risks count, Robert finds his ego belittled when his wife Juliette insists he is the best second violinist she knows. Switching positions with Daniel would alter the sound they have spent years refining. In the feud, Robert consummates his casual affair with his occasional jogging companion, much to the dismay of Juliette. With all that transpires, the industrious Daniel, considering a proposal by Peter to take in Nina, a sub-cellist with which they have played well before to finish the season, reluctantly romances Robert’s and Juliette’s younger daughter Alexandra (Imogen Poots), who just so happens to be living in the city on her own and taking lessons from him. To move consciously now is to move ethically. The relationships and egos presented in A Late Quartet are revealed to be more entangled and enthralling as the story progresses. Compatibility preserved in The Fugue’s musicianship has much more to do with the intimacies the members share with each other than the professional and artistic ties that bind them to the music played as one.

Just as rapt as the main characters’ frailties and flaws is the way in which New York City is depicted in winter, an expression of playing with exteriors and interiors. Where there exists a cacophony of sounds in a metropolis like NYC and the streets seethe with automobile and pedestrian traffic, somehow exteriors in the film become quiet, neutral landscapes. The snow-covered sidewalks and frozen ponds of Central Park serve more often than not to sublimate characters’ emotions. It is inside taxi cabs, apartment rooms whose walls are bathed in bold colors, where fervor shows its embittered face. As Robert admonishes the cautious Daniel—more a prelude to his courting Alexandra than a comment about carrying his “safe” playing to obsession—”Unleash your passions!” This tête-à-tête impels both to see beyond what they think is best for the survival of the quartet and directly into their relationship.

All this is done to disclose the beautiful and often insular nature of a musician’s connection with his or her instrument. Potential lies within—the stringed instrument must be played in order for sound to resonate in the chamber defining its body. Perhaps it is then, with no required verbal communication, feelings of the musician are exposed. For Robert, Juliette, Daniel, and Peter, the spaces they inhabit become the chambers where emotional revelations reverberate. If only they would heed the sounds they make, rather than airing their grievances in the form of running their horse-hair bows across whining strings, we could be assured The Fugue maintains its esteemed position in New York’s classical music scene after Peter’s last performance.