Painting has always courted change with breathless, barreling enthusiasm—and a medium that’s declared dead so often has done well in choosing resurrection as its lifeblood. New technologies have invoked new modes of experiential expression, imbuing painterly practice with a relentless urgency to prove its relevance in an ever-shifting marketplace. So-called post-digital painting discloses its intent to account for modernity through the prism of an ancient art form. Whether that connection is antithetical, integrative, or contentious varies, but cognizance remains the key to its application, and art history is replete with examples of parallel dialogues in which new technologies refresh artistic perspective. Author Dominique de Font-Reaulx posits the daguerreotype’s advent as impetus for Impressionism’s soft-focus finish; renowned painter David Hockney theorized that stringent realism in Renaissance art was a byproduct of new optical aids, most prominently the camera obscura. Yet what happens when an artist tries to capture the essence of new technology in two dimensions? That question is interrogated by Salem’s Peabody Essex Museum (PEM) in its current exhibition, American Epics: Thomas Hart Benton and Hollywood. On view through September 7th, it provides an insightful and novel perspective on the nearly forgotten former art-star, and his fraught relationship with Hollywood. The exhibit will travel to the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, then to the Amon Carter Museum, and the Milwaukee Art Museum as the final venue.

Benton (1889-1975) may no longer be a household name, but he enjoyed significant celebrity in his prime. Widely considered a preeminent muralist among 1930s American Scene painters, his rich, stylized depictions of preindustrial agrarian life—along with his more controversial investment in representational narrative as social activism—typified the anti-abstraction, Regionalist movement. He graced the cover of Time magazine in 1934, and was commissioned for film advertising campaigns and Whitney Museum murals alike. He mentored Jackson Pollock. He exhibited internationally, and enjoyed close relations with Marlon Brando, Jimmy Cagney, and other Hollywood stars. Yet in spite of all his accolades, there hasn’t been a Benton retrospective in over 25 years, an oversight PEM’s George Putnam curator of American Art, Austen Barron Bailey, aims to correct. The exhibition, centered on a large scale 1937-8 mural of a showgirl on set, bears the apt and telling title Hollywood.

In 1919, Benton, a Missouri native, moved to Fort Lee, New Jersey to find work as a prop and set designer on silent film productions. Once talkies came on the scene, however, his involvement with the industry grew more complicated. In an unfinished account of his time in Hollywood (one of his three published autobiographies), Benton insisted that the Golden Age entertainment machine was “fake” and “empty,” but nevertheless he continued accepting publicity assignments for movies including The Grapes of Wrath and The Long Voyage Home, projects whose reach would outstrip that of his public works projects. He was particularly captivated by the story-telling capacity movies monopolized in the popular consciousness, and a quotation emblazoned on the entryway of the first gallery sums up this attitude: “History was not a scholarly study for me, but a drama.” Hollywood definitely brings the drama. There’s illusionistic three-dimensional space, garishly projected light-sources, and, naturally, a scantily clad actress posing amid the bustling central activity. LIFE magazine commissioned Benton for Hollywood and forty-odd ink drawings to accompany the painting after the successful release of his 1937 book, An Artist in America. During his subsequent month-long assignment in Los Angeles, Benton produced hundreds of preliminary sketches, or “notes”, depicting behind-the-scenes moments in motion-picture making.

These lively, intimate pieces represent the heart of this exhibit, which explores Benton’s relationship with film by pairing his images with rolling footage. Some combinations are little more than obvious context—the Grapes of Wrath lithographs hang in the same room as an embedded screen console playing footage from the film—while others are associative, like the mural-size, noisy projection of A Star Is Born, rattling ten feet away from the spot-lit space where Hollywood hugs the wall. While the film tie-ins function well overall—Matthew Bernstein, a professor in Emory University’s Department of Film and Media Studies, served as a consulting film curator—the Hollywood-themed exhibition production occasionally falls flat. Pockets of darkness detract from any atmosphere the theatrical lighting choices might have achieved, and the movie paraphernalia sprinkled throughout—director’s chairs, theater seats—seem more like misplaced props than art objects contributing to a deliberate environment.

The exhibit marches more-or-less chronologically through Benton’s career, with the video clips providing context and reminding viewers of dialogue between media throughout. At times, this choice feels distracting, but it also honors Benton’s relentless didacticism: he was committed to primary colors and broad generalization, and curatorial notes for the exhibit repeatedly mention Benton’s concern for “capturing certain American types.” Perhaps most importantly, the exhibition is designed to prompt viewers to look beyond Benton’s explicit, commercial link to film as a key influence on his work, and to explore the artist’s oeuvre as fundamentally cinematic—a static metaphor for early film’s entrancing accessibility. Popular art has always trafficked in archetype—perhaps even erring on the side of prejudice—and Benton’s work doesn’t stray from that precedent.

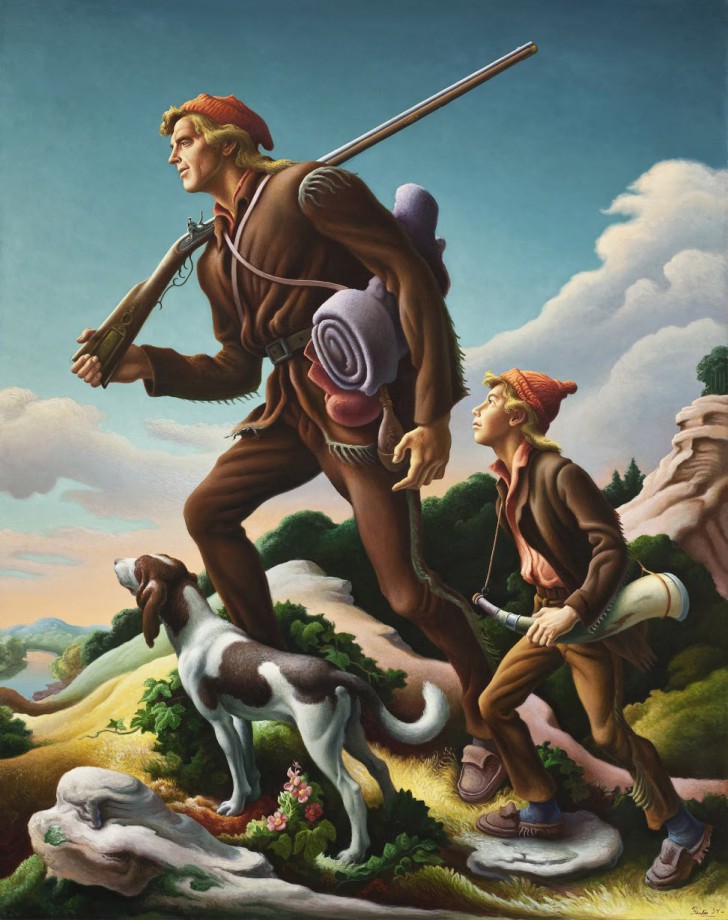

A 1942 Paramount newsreel titled War Art Creates Sensation plays loudly upon entry to the exhibit’s World War II Room, which follows the galleries dedicated to the artist’s more glamorous works. Here, viewers watch Benton somberly skulking about his New York opening, warning America against complacency in the face of a foreign war. He scowls as the camera pans to a crowd of gallery-goers in black tie surveying his Year of Peril painting collection, cocktails in hand. A six-foot-plus canvas entitled Exterminate! hangs directly opposite the video installation. The piece portrays a heavily caricatured, shirtless embodiment of Nazi Germany (Chaplin mustache and all) standing behind a similarly steroid-riddled representation of Axis Ally Japan, who begins to slump as a lithe American soldier stabs him in the chest. As a painting, the work is fluid and dynamic, with clear nods to surrealism, Diego Rivera, even newspaper cartoon satire. Notwithstanding, it is unquestionably a work of propaganda, and even more strikingly, Benton’s portrayal of the Japanese soldier betrays unmistakable racism. Exterminate! isn’t the only problematic canvas on view at PEM—Minstrel Show feels far more like nostalgia than reportage; Negro and Alligator illustrates a prejudicial prank in breezy earth tones—but it is the only such work that omits commentary on Benton’s questionable attitudes. Further, even when the labels do address race directly, the analyses are brief and superficial, without any honest criticism beyond simple acknowledgement. This is not an anachronism issue, necessarily—it’s a tone problem. That all artists are products of their era is given, and any painter dedicated to mythologizing 1930s and ’40s American identity will seem out-of-step with political attitudes in 2015. Nevertheless, we hold our institutions liable for framing these issues in a responsible, ethical fashion, with equal attention to providing a contextual reference frame for the artist’s attitudes, as well as a contemporary criticism of any inherent prejudices that qualify our estimation of that artist. American Epics remains fascinating, yet it falls short of this essential goal to interrogate even the ugly underpinnings of an artist’s themes.

Another movie reel from 1942 loops silently on a wall directly behind Exterminate!, a punchy call for African American recruits, with various draft demographics adorning the adjacent wall. Negro Soldier, the companion painting, hangs a few feet away, depicting a young African American man in uniform, bayonet aloft, standing before a low, molten horizon punctuated by a tank grinding into the distance. According to the commentary provided, Benton intended this figure as a criticism of army segregation, but no visual cues support that conclusion. The painting’s proximity to Shipping Out—a tender portrait of a young man gazing over his shoulder towards the viewer as he boards a barge to war—further illuminates the discrepancy, in which subjects of color are painted from behind, at three-quarters, or in profile, and with minimal attention to discriminating between the appearance of each minority individual.

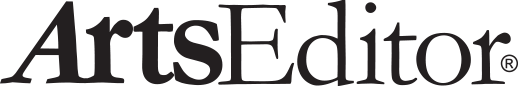

By contrast, Benton chose to dignify his white sitters with frontal composition, eye contact, and feature specificity. These inequities are not deliberately malicious—to wit, the exhibit opens with the fourteen-panel mural series American Historical Epic, which expounds upon the persecution of oppressed minorities in the country’s early history. These were uncommissioned works, and a credit to Benton’s overt and impassioned leftism. Still, his bombastic, wavy brushwork and indiscriminate facial modeling suggests a persistent, underlying prejudice found subtly throughout the exhibition. Its final segment focuses on Benton’s 1950s and ’60s depictions of the American West in saccharine palettes heavily influenced by Westerns. His final film commission hangs at its center—a 1954 promotional painting for The Kentuckian—in which a tremendous, detailed paean to Burt Lancaster is flanked on all sides by diminutive, cookie-cutter Native Americans—faceless, anonymous, and irrelevant, whether in conflict or repose.

The PEM needn’t sterilize Benton’s history, nor should an exhibition focused on escapism and the dialogue between painting and film necessarily delve deeply into critical analysis of the artist’s prejudices. Thomas Hart Benton’s work might have not aged perfectly, but that doesn’t erase his impact on subsequent artists and movements. Notwithstanding, there is potentially controversial imagery on display, and surprisingly little context or commentary is provided—if anything, the institutionally sanctioned platform swings from celebratory to intolerant in the span of a room, which seems strikingly insensitive in the age of #BlackLivesMatter. This may ultimately be attributable to a bloated sensibility: American Epics frequently strays from the Hollywood / fine art dialogue it set out to explore, and correspondingly many of the works like Exterminate! are left to fend for themselves. Benton’s work might have not aged perfectly, but that doesn’t erase the impact it’s made on artistic movements hence. Many of the topics raised by Benton’s paintings are still pressing today. Just as pressing are the reasons his expression of these topics could be considered exclusionary. The same, of course, could be said of movies, then and today.