It’s fascinating when a group of 400-year-old religious paintings can elicit strong emotional reactions from a modern museum visitor. “Fresh,” “visceral,” and “passionate” are words not often associated with the biblical narratives that line so many gallery walls. But this lofty and sometimes remote-feeling subject matter is given a compelling down-to-earth twist in the revolutionary work of Italian artist Caravaggio. Eschewing the idealized classical face and figure prevalent during his time, Caravaggio used ordinary working-class people as his models. While sticking to traditional themes, he captured every wrinkle, flaw, and gesture of his subjects with a startling naturalism that was groundbreaking in its day. Working in early 17th Century Italy, the realism and expressiveness of his figures feels so contemporary and immediate that some scholars laud him as the “first modern artist.”

Sixteen large-scale oil paintings created over the last turbulent four years of Caravaggio’s life are currently exhibited together at the National Gallery, London in Caravaggio: The Final Years, on view through May 22nd. Co-organized with the Soprintendenza Speciale per il Polo Museale di Napoli, this exhibit is unique in that it focuses on works that are lesser known than those from his earlier Roman years. Even people very familiar with the artist’s work will most likely encounter something new, as some pieces have not been lent outside of Italy before.

Working during the Catholic Counter-Reformation, Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio (1571-1610), named after the town in which he was born, pleased many of his religious patrons because he added an approachable human touch to his work. This seemed to fit the Vatican’s plan to reinvigorate the Church and combat the Protestant Reformation by reaching as wide an audience as possible. Caravaggio’s personal life, however, was tainted with so much violence that it jeopardized his career. Frequenting seedy taverns and prone to barroom brawls, in 1606 he killed a man in a duel and was forced to flee Rome. Spending the last four years of his life traveling to Naples, Malta, and Sicily, searching for work and ever hopeful of a papal pardon, he produced more introspective and subdued paintings reflecting the psychological toll his lifestyle had taken. Only in his thirties when he died prematurely, Caravaggio epitomized the stereotype of the artist as a tormented genius.

Held in the basement level of the National Gallery’s newer Sainsbury Wing, the six rooms that comprise the exhibit are appropriately intimate in scale. Creating the reflective atmosphere of a chapel, the dim lighting and dark, jewel-toned walls are a subdued but fittingly dramatic match for Caravaggio’s theatrical scenes. Timed ticketing maintains a relative order in what is a well-trafficked space. It’s worth the occasional jostling and neck craning through the crowds to spend time quietly contemplating the works, and the available acoustic guides help flesh out the experience with useful background information.

The first piece in the exhibition is The Supper at Emmaus from 1601 and is in the National Gallery’s permanent collection. This large oil and tempera on canvas depicts the story of two disciples learning of the Resurrection. Walking to Emmaus, they were joined by Christ, who they did not recognize until they all sat down to supper and Christ blessed the bread. Caravaggio has captured that revelatory moment at the table, and the viewer is drawn into the astonished expressions of the apostles. Christ sits serenely in the middle of the picture with his right hand raised in blessing, but it is the two older, bearded apostles flanking his side and the innkeeper standing next to him that add an immediacy and physicality to the scene. The disciple on the right throws out both arms, and one hand seems to jump off the canvas. The one on the left grasps his chair as if to leap out of it, and the viewer is confronted with his jutting elbows, complete with a tear in his overcoat. The innkeeper, looking like a stocky Italian peasant, is standing bemused, trying to comprehend the immensity of the moment.

Compositionally, Caravaggio has used the table and the figures to dominate the canvas, creating an intimate feel, as if the viewer is sitting down with them. Among the items served at the meal, an overflowing basket of fruit is perched on the edge of the tablecloth, looking like it will topple over at any moment. The background is darkly shadowed, employing the drastic light and shade technique of chiaroscuro the artist is so well-known for. This work is hung next to another Supper at Emmaus from the Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan—painted in 1606, soon after Caravaggio fled Rome. Similar in scale and composition, the later work is however more pensive and reflective, the wild gesturing gone. The tones are more muted and brown, the figures are clustered to the right, and the background has gone completely black. The innkeeper is now joined by an old serving woman whose downward gaze and deeply wrinkled brow seems to reflect the new overall somberness of Caravaggio’s painting.

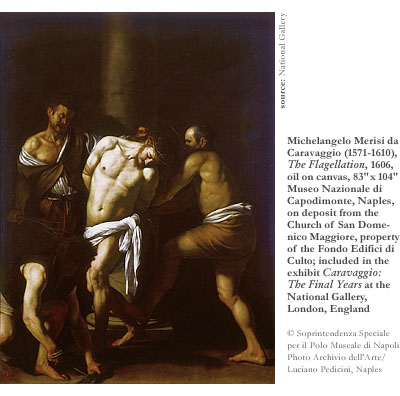

While all sixteen paintings in the exhibit are masterpieces, it is worth noting a few in particular that marry grand subject matter with the gritty realism the artist is celebrated for. The Flagellation, from 1607, is a large-scale work showing Christ being bound to a column for whipping before his crucifixion. Christ’s graceful body is twisted into an agonizing pose, and the rough muscular bodies of his tormentors show the physicality necessary for this brutal job. One guard is yanking Christ’s hair, forcing a few droplets of blood from the crown of thorns to splatter on his chest. Another has placed his bare foot on Christ’s back leg to steady himself while securing the ropes. And a third man is bent down in the foreground, binding the sticks that will be used for the flagellation. The scene captures a tense anticipatory moment that evokes empathy from the viewer for what is about to transpire.

The Crucifixion of Saint Andrew, 1606-7, is another heart-wrenching piece, placing the viewer right at the foot of the cross, as though witnessing the execution firsthand. Andrew preached from his cross for two days, stirring the crowd to win his release. However, when the guards tried to take him down, they were miraculously paralyzed as Andrew’s prayers to die on the cross were answered. Once again, the sublime nature of the painting is imbued with realistic detail—Andrew’s neck and face are sunburned, a guard’s feet are barefoot and dirty, and a woman standing at the foot of the cross has a goiter on her neck, a common ailment among the poor during Caravaggio’s time.

Taking a more classically themed and humorous turn is Sleeping Cupid from 1608. Made for a Florentine Knight of Malta pledged to chastity, Caravaggio turned the pretty little cherub into a snoring, chunky imp. The god of love is fast asleep, wings spread out, with his mouth open and his head resting on his quiver full of arrows. Questioning ideas of profane love and beauty, Caravaggio created a simultaneously charming and unsightly Cupid.

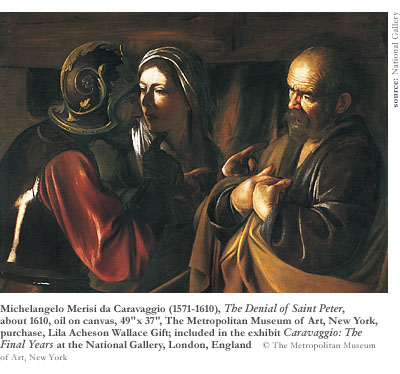

Caravaggio explores dramatic confrontations in two works from the last year of his life, The Denial of Saint Peter and The Martyrdom of Saint Ursula. Completed in 1610, The Denial is both concise and intense as Peter denies knowing Christ after his arrest despite three fingers accusingly pointed at him. In The Martyrdom, which some scholars argue is his final painting, Caravaggio has captured the terrible moment when the spurned pagan prince of the Huns releases an arrow that pierces the virtuous Princess Ursula’s heart. The young, beautiful Ursula stares transfixed at the arrow in her chest and in shock. The prince, who is still holding the bow, seems to immediately regret his transgression. His wizened face looks crestfallen, as if fully comprehending his crime.

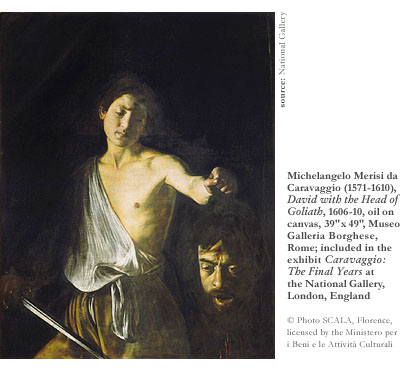

The last painting in the exhibit, hung on its own in a small gallery, is the haunting David with the Head of Goliath, and should not be missed. Scholars debate the precise age of the work, but it is placed somewhere between 1606 and 1610. A young David looks down on the freshly severed head of his enemy. Hardly exhilarated by his triumph, the boy instead looks pensive, suggesting his disgust with the whole enterprise. Holding Goliath by the hair in his left hand and holding his sword in the other, David’s pained face and furrowed brow gives the painting an anxious feeling. Perhaps this reflected Caravaggio’s personal awareness of what it felt like to kill a man. Most shockingly, the large head of Goliath is seen as a self-portrait. Freshly severed from its body, his head still seems alive with his mouth caught in a scream and his eyes wide open while blood gushes from the neck. The look of anguish is chilling and could easily reflect the inner turmoil of the artist. Is Caravaggio damning himself for his mortal sin or is this a mea culpa meant to elicit sympathy from the papacy that condemned him?

These kinds of troubling and beautiful tableaux evoke an impassioned response in contemporary viewers that can be lacking in drier art historical exhibitions. Painted so many years ago, the work deftly avoids the trap of feeling obsolete. These highly personal and emotionally charged scenes have sustained Caravaggio’s standing as a relevant painter today.