“Don’t give me any of that ‘intelligent life’ stuff. Find me something I can blow up!”—Lt. Doolittle (Brian Narelle)

It has been my belief that the best way to gain an appreciation for an established filmmaker is to visit his early work. In those first rough-hewn gems one can see not only the promise of brilliance to come, but also moments of inspiration unique to time and place, never to be seen again. For example, while critics have smirked at Alfred Hitchcock’s dark humor in his popular films like Psycho, who would have known that in his early work, like The Lady Vanishes or Young and Innocent, he was flat-out funny? Or how about cinematic svengali Stanley Kubrick? It seems impossible to imagine one of his films with a positive, upbeat ending—excepting 2001: A Space Odyssey‘s ambiguous-at-best conclusion. But take one of his earliest works, 1955’s Killer’s Kiss, and there you have it: the glimmer of genius, with something entirely unique when placed alongside the auteur‘s body of work. It is with this interest in a director’s less-known early work that I visit John Carpenter’s 1974 opus, Dark Star. As with Kubrick, it plants the seeds for a long and prolific career in genre filmmaking, and as with Hitchcock, this early work is funnier than any of Carpenter’s later works.

To hear the pitch, one might just get the wrong idea. It is a science fiction tale of isolation, desperation, and technology gone awry. It features four astronauts; their cryogenically frozen, dead captain; a vicious alien; and nuclear “smart bombs” that are too smart for their own good. At first glance, the film’s pedigree-before-the-fact is impressive. John Carpenter, director of 1982’s The Thing, as well as horror classic Halloween, directs. Co-writing with Carpenter is Dan O’Bannon, whose body of scripts includes Alien, Total Recall, and 1986’s Invaders From Mars. O’Bannon also stars as Sgt. Pinback, an astronaut with a secret. One must note, as said before, that this is their earliest work. It began in 1970 as a student film for USC, alma mater to the likes of George Lucas and Ron Howard. By the time the film was finished, four years later, it was 68 minutes long and had cost $55,000 to make. After a promising festival run, Hollywood producer Jack Harris asked the filmmakers to add some footage to make it a full-length feature, ready for theatrical release. O’Bannon, in his introduction letter to the 1983 home video release, recalls what happened next:

“…on opening night, John Carpenter and I went around to a few of the 40 theaters it was saturation-booked into, to see how people liked our movie. It was our very first feature film and we were both wound up tighter than a drum. So we introduced ourselves to the theater manager and said we’d like to take a peek inside to judge the audience reaction. In the sourest tone of voice imaginable he said, “What audience?” There were 5 people in the house and they looked like they were attending a funeral.”

The downside to making a cult classic is that, usually, it has to bomb first. Fortunately, both got back on their feet—Carpenter with Assault on Precinct 13 and then Halloween, O’Bannon with Alien—soon enough. The problem may have been a misunderstanding of tone. O’Bannon wrote in his introduction, “This movie is a comedy. I wanted to be sure and clarify that right up front, because when the film was first released to the paying public they didn’t seem to realize it was supposed to be funny.” It’s true; the trailer, included on the DVD, makes Dark Star seem like any number of pre-Star Wars sci-fi of the 70s: low-budget, well-meaning, but ultimately, silly. If, however, those in charge of promoting the film had presented those attributes as deliberate and the tone as intentionally silly, the film would have faced a much more prepared audience.

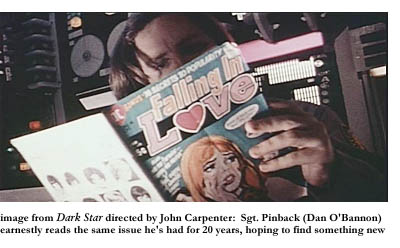

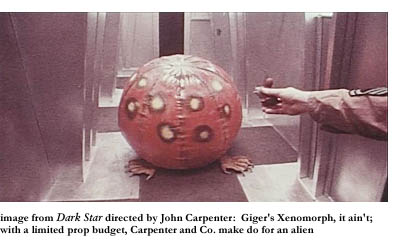

With that in mind, let’s take another look at the concept: the four astronauts, deep space’s version of Easy Rider, spend their time going from planet to planet, annihilating those unstable bodies that would pose a hazard to colonization. They have been on this mission for 20 years, with no hope for homecoming. Their captain, Cmdr. Powell, has recently died as a result of a faulty seat panel. Add to that the fact that their entire supply of toilet paper has been destroyed. Pinback, reading a romance comic book during the credits, is clearly the comedic foil to the otherwise serious crewmen on board. One of the film’s highlights involves his video diary, showing not only the passage of time, but Pinback’s emotional, mental, and physical decline over that time. During one of his outbursts, the computer heavily censors his entry. Owing to this, as well as a deliberately blurred-out wall of centerfolds in the crew quarters, Dark Star received a “G” rating from the MPAA. In another scene, Pinback has to wrangle the ship’s “mascot,” a bulbous, tittering alien. No joke: they used a beach ball, stuck latex claws to the bottom, and painted spots on it. Once again, this is a comedy, so we can allow it. Otherwise, it would just be sad. Pinback’s encounter with the alien is very cartoonish, thanks in part to the addition of Rossini’s Barber of Seville (the basis of a classic Bugs Bunny short) playing in the background.

Taking in all of his absurd moments, it’s clear that O’Bannon gave himself the best bits, leaving expository dialogue to trigger-happy Boiler (Cal Kuniholme), Lt. Doolittle (Brian Narelle), and the loner of the crew, Talby (Dre Pahich). Still, they each have their moments, such as Doolittle’s nostalgia for his surfing days back on Earth (a setup which has the most bizarre payoff imaginable), or Talby’s fascination with a mysterious asteroid field. Boiler’s interests are mostly limited to target practice. Interestingly enough, the late Cmdr. Powell gives some posthumous advice to the Doolittle, a la Ben Kenobi in Star Wars. Some of the most sincere science fiction dialogue comes from Bomb #20 (Adam Beckenbaugh), a distant cousin of 2001‘s HAL 9000.

Originally shot on 16mm, the image quality is less than pristine. But keep in mind that it’s most likely the best this movie will ever look. VCI and the Roan group put together this “special edition,” featuring both the original 68-minute and extended 82-minute cuts. For this review, I screened the extended version. Seamless Branching, the same technology that allows for two versions of The Abyss on DVD, picks and chooses which chapters to play. In the menu, you can see chapter 5, “Extra Scenes from 1974 release.” The video is letterboxed at 1.85:1 without anamorphic enhancement, and it doesn’t look likely that it will be made 16×9-ready anytime soon. One’s interest in getting this disc should be historical, not visual.

Originally shot on 16mm, the image quality is less than pristine. But keep in mind that it’s most likely the best this movie will ever look. VCI and the Roan group put together this “special edition,” featuring both the original 68-minute and extended 82-minute cuts. For this review, I screened the extended version. Seamless Branching, the same technology that allows for two versions of The Abyss on DVD, picks and chooses which chapters to play. In the menu, you can see chapter 5, “Extra Scenes from 1974 release.” The video is letterboxed at 1.85:1 without anamorphic enhancement, and it doesn’t look likely that it will be made 16×9-ready anytime soon. One’s interest in getting this disc should be historical, not visual.

Pretty much the same goes for the audio department, which the box (a standard keepcase) claims is “Dolby Digital 5.1.” I didn’t notice any surround activity on my Cambridge Soundworks Desktop Theater 5.1. It’s not such a big deal, because the only moment in the movie worth cranking the speakers for is the opening credits, where, of all things, a country-western ditty, “Benson, Arizona,” plays. John Carpenter composed this song with Bill Taylor, who wrote the lyrics and worked on the film’s effects. Listening carefully, one will notice that the lyrics allude to Einstein’s theory of relativity: “The years tear us apart/I’m young, and now you’re old,” a concept touched upon by the astronauts, 20 years out, but only three years older. Boiler asks Doolittle what Talby’s first name is. Doolittle replies, after a long pause, “what’s my first name?”

The first name in sci-fi/horror inventiveness is John Carpenter. He’s certainly come far in the past 25 years, but if you really want a look at where it all started, check out Dark Star. And remember, it’s a comedy. They know it looks like that.