There is a convention of reverence involved in most current figurative painting. As if a painting that displays a figure must be about the figure, because of an inherent iconic representation of something greater than itself.

Then every once in a while, there is a figure about painting.

It’s hard, on first glance, not to tag Jorge Drosten’s portraits as a Latin American bubble thrust into Newbury Street and looking inward; they’ve got all the symptoms of what we’ve come to expect as “pre-Columbian.” The vibrant warm colors and tropical settings call to mind the familiar folkloric tradition that continues to inspire and re-inspire the turbulence of art throughout Latin America. Drosten’s paintings of twin dolls, for instance, peaceful and benevolent, are not without idolatrous authority. In the exhibit Twin Allegories, on view at Arden Gallery through July 31st, Drosten’s human figure, however, is only a thinly-stretched skin over a massive resurgence of something deeper.

Within the last few years, Newbury Street has seen a return of figurative painting and sculpture as a vessel for what people often call a celebration of the human form. This tends to carry with it, above all else, psychological or spiritual implications. A “looking inward,” without regard to an environment outside the individual. Jorge Drosten’s work, on the other hand, seems to twist violently away from this convention. His “humans” are tools of their environment—practically byproducts. And his pre-Columbian element isolates him from other Boston art as well, as it is literally of foreign influence.

Consider, for example, the human form in the work of Sam Messer. Or in that of Mark Chatterley, currently exhibiting just next door at Chase Gallery. The figure is corroded, bent, and the use of texture and color recall German modernists such as Emil Nolde, self-enclosed and concerned with (as he calls it) “the intense and often grotesque expression of power and life in very simple forms.” Drosten’s grotesque expressions are indeed intense, but they are not of life.

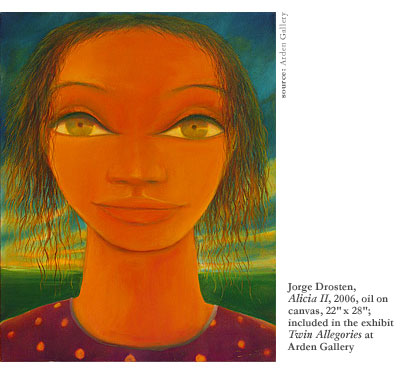

So with the resurgence of the human form as a platform for expression, is it okay for a portrait to not have psychological profundity in the way that the modernists would have demanded? Ernst Kirchner no doubt would have sneered at the exact same thick-lipped “Mona Lisa smile” on every one of Drosten’s portraits. But Drosten’s vocabulary stems from a convention still very new to Boston, and challenges the role of a portrait, prompting a reconsideration of the term “expression.”

Admittedly, pre-Columbian influence does not make a “Hispanic painter.” Nevertheless, Drosten’s work does represent a trickling in of Hispanic influence, which is still relatively new in this city. On a macro scale, it’s interesting to consider any influence of the Hispanic art world on the United States, after the heavy influence this country held over that world during the 1950s and ’60s, when most of the exhibitions conducted in Columbia were operated by major American industries—particularly affiliates of Standard Oil, Braniff Airlines, and Shell and Phillips Oil Companies. The subsequent rise of inter-American art competition led to the suppression of pre-Columbian themes. It will be interesting to watch over the coming years to see if this trickling becomes a downpour.

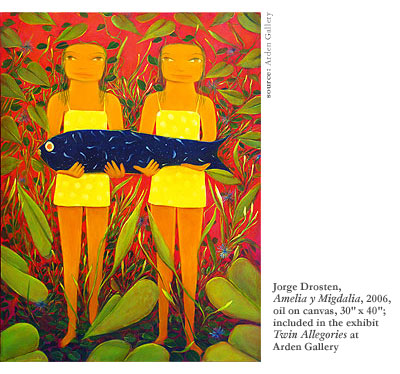

Two tell-tale pre-Columbian aspects of Drosten’s art are its flat shapes and the repetitive, single face that peers out from every single canvas in the room under different guises. That’s to say, the Captain, the Tattoo Man, the twins, and every other figure portrayed share the same oval eyes, the same flat nose (chata), and the same wide grin. They’re not individuals, but rather manifestations of a common face. We see this idea in pre-Columbian religious artwork, and it comes back tenfold in Mexican murals—waves of aristocrats in Jose Clemente Orozco’s work, waves of proletarians in Diego Rivera’s, and waves of American soldiers in David Alfaro Siqueiros’—all with the same face. It makes a clear point. At Arden Gallery, every last canvas stares back at you with the same haunting eyes and faint smile.

This creates a funhouse effect. There is a feeling of the uncanny, like flipping through a photo album and seeing the same face on every member of the family, with the same expression and the vibrant, supersaturated color palette characteristic of Caribbean art. Moreover, each and every subject here is literally offering something to the viewer, such as a snake in Tattoo Man, a ship in El Capitán, a fish in Amelia y Migdalia, or a pair of pearls in Anadia y Anidia. It’s the only significant thing that separates one work from the next, and thereby the painting’s entire identity—there, held out before them in both hands, for you. How’s that for a psychological rendering of the human form? Really, this entire exhibit is a single collective piece with a cumulative haze. And each painting is but an agent to that greater effect.

There is a drawback to this unique “collective experiment.” Many viewers, expecting a variety of ideas integrated (but not united), may find it repetitive. It is, after all, only one face, distributed to a whole room full of portraits. Seen in that regard, the work lacks structure and depth because there’s no interplay of ideas. It’s basically an extrapolation of an idea found in a single painting. There’s only one experiment in the whole room.

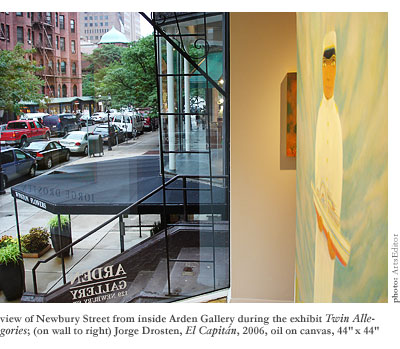

Consider one of the paintings in a space by itself—El Capitán, looking out at Newbury Street from his post by the window and offering us his ship. The face with the oval eyes and the Mona Lisa smile, ideal for repetition throughout the gallery, loses a layer of purpose. By itself, it could be any face, a pleasant happenstance of the folkloric prototype. When the walls are covered by Drosten’s “allegories,” the single visage serves as a common thread to create a stronger, more unified idea. The work is beautiful and unsettling. But any one of the paintings alone is only beautiful.

The question remains: is our interpretation of the psychological depth of a painting necessary to our appreciation of it? A common expectation is that there must be multiple layers in the representation of the figure. We’re still standing on the shoulders of Lucian Freud, David Hockney, and even Egon Schiele. We find ourselves still close to their philosophies and their approach to the question of “us.”

But Jorge Drosten isn’t accessing the same history most other figurative artists are. His is another convention entirely, and its intentions are different. In this introduction of pre-Columbian influence to Newbury Street, this artist has separated himself from the more popular vein of New England art, almost to the point of creating the hyperbolic folkloric prototype: the Latin American painting, made more so by its immersion in the Boston tradition. The function of the figure in its space is different than that which we’re accustomed to. It’s thin, fleeting, central in placement but marginal in its role. It doesn’t elicit empathy and it doesn’t claim to. If there is a psychology, it’s in the painting itself, not the figure. Don’t look for psychology in Anadia y Anidia, but accept their pearls and say “thanks.”