There has hardly been a time when a Coen brothers’ film has not been worth seeing. With fare as wildly diverse as the boisterous comedy, Raising Arizona, to the meditative and eerie Barton Fink, to the 1997 Academy Award winner for Best Original Screenplay, Fargo, the Coen brothers have managed to straddle two very different worlds. They have become virtual critics’ darlings and can boast modest commercial success. Before the critical acclaim and repeated success at various festivals (Cannes and Sundance, among others), the Coens crafted a small masterpiece. Blood Simple, their debut film, was originally released in 1984. The Director’s Cut of this film was released in July of this year, provoking many laudatory responses from Coen critics and fans.

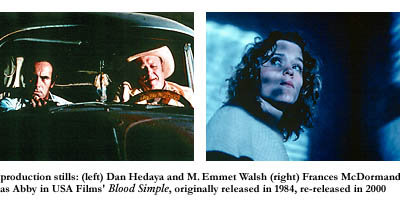

Blood Simple‘s plot is typical of the noir genre—Marty (Dan Hedaya) is a jealous West Texas husband who conspires to have his wife (Frances McDormand) and her lover, Ray, (John Getz) killed. Marty hires Visser (M. Emmet Walsh) to do the deed, but manages to end up on the receiving end of his wife’s pearl-handled revolver, which was lifted by Visser. Before Marty’s demise, Visser manages to convince him that he did kill his wife and her lover, using doctored photographs as evidence. Ray stumbles onto the scene, after Visser has fled, and suspects Marty’s wife, using her pearl-handled revolver as his evidence. He attempts to cover up her supposed crime, only to find that Marty is not really dead…and so on. The plot here is important in the way all neo noir plots are—the characters slip in and out of roles with surprising ease. That is, as the film opens, we tend to identify with the lover, Ray, rather than with Marty, the scheming inattentive husband. The characters make a rapid shift in the scenes where Ray attempts to cover up his lover’s supposed crime, with no questions asked. As we discover that Marty is not really dead, we watch as Ray finishes the job. In an instant, Ray is no longer worthy of our trust or sympathy, because his persona rapidly shifts from savior to criminal, despite his subsequent remorse. With this transition, the characters become fleshed-out and invariably more interesting.

With a series of understated performances by all parties, Blood Simple‘s success owes much to the brothers’ experimentation with style that is now, several films later, unmistakably theirs. That is, Simple is the groundwork on which Fargo, perhaps their best-known film, is built. Stylistically, many elements are the same—the feelings of helplessness and vacancy in Ray and in Fargo’s flawed main character are similar. Simply substitute North Dakota fields of ice and snow for the tilled farmland of West Texas. The immensity of the landscape and the overwhelming disparity of being so small and vulnerable is essentially the same, no matter the setting of the open space.

There is a reason why so many noir films take place in seemingly empty and open space. The vastness of the West Texas landscape, the almost-emptiness of the country in Blood Simple emphasizes every action. There is nothing but the methodical motion of oil drills to dot the skyline. There are miles of open road, straight lines of highway…and little else. It is this open space that enables the Coen brothers to focus on detail, and deem every action significant. These wonderful details—the infamous pearl-handled gun, Visser’s engraved lighter, the doctored photographs of Ray and Marty’s wife, the blip of Marty’s computer screen—seem all the more eerie, claustrophobic even, as they appear and reappear in meticulous and timely fashion.

When speaking of the Coen brothers, most critics cannot help but acknowledge that most of their movies play like an elaborate series of jokes, of which the audience is likely unaware upon the first viewing. Though this statement is a sweeping one, it is true that the Coen brothers manage to give the impression that their films are purely situational. That is, one can easily classify Blood Simple as their “noir picture”—a flick that tells the story of a husband who attempts to exact revenge on his adulterous wife and her lover. But to say just that reduces the film to a one-gag joke.  (Keep in mind that the Coen brothers rarely approach any subject from a one-joke mentality.) Upon subsequent viewings, Blood Simple becomes a figurative and literal execution of the characters. It is a film not only about a vengeful husband and unfaithful wife, but also about how details propel the characters into situations that force them to change roles. This forces us, as the audience, to rethink our initial impressions of the characters. Who do we trust? With whom do we identify? By the end of Blood Simple, our desire to identify with a particular character has been deflected several times. This is the Coens’ great “joke” of the film—we identify with everyone and no one at once. Perhaps an appreciation of this position comes with multiple viewings. For me, the beauty of Blood Simple is the visualization of how the characters negotiate between their various (and perhaps dueling) facets of their personalities. It makes for deliciously twisted fun.

(Keep in mind that the Coen brothers rarely approach any subject from a one-joke mentality.) Upon subsequent viewings, Blood Simple becomes a figurative and literal execution of the characters. It is a film not only about a vengeful husband and unfaithful wife, but also about how details propel the characters into situations that force them to change roles. This forces us, as the audience, to rethink our initial impressions of the characters. Who do we trust? With whom do we identify? By the end of Blood Simple, our desire to identify with a particular character has been deflected several times. This is the Coens’ great “joke” of the film—we identify with everyone and no one at once. Perhaps an appreciation of this position comes with multiple viewings. For me, the beauty of Blood Simple is the visualization of how the characters negotiate between their various (and perhaps dueling) facets of their personalities. It makes for deliciously twisted fun.

The Coen brothers do have fun with the Director’s Cut of Blood Simple. They have taken the word “cut” literally, and shaved several minutes from the 1984 version. They have added a hilarious intro to the film—an American Movie Classics-esque introduction to the “classic” that is Blood Simple. All of the “boring parts” (in the words of the narrator) have thankfully been removed, as the print has been restored to its original splendor. This is, of course, said tongue-in-cheek, and is a fine example of traditional Coen wit. A joke about their inexperience when making Blood Simple is fair game for them—a joke at the expense of the audience, never. See this film, and then see it again.

Blood Simple is playing at the Kendall Square Cinema, the Embassy, and Coolidge Corner.