At the Berkshire International Film Festival, there are no red carpets leading to press photography shoots. No stretch limousines or swarms of interviewers eagerly waiting to interrogate big movie stars. Instead, there are intimate parties with house bands and an easy air of mingling. There are beautiful, ornate venues, like the Mahaiwe Performing Arts Center in downtown Great Barrington, which hosted the opening night film and ceremony. There’s also just as much enthusiasm, if not more, than at larger, more popular American film festivals like Sundance and Telluride, but tucked away right here in Western Massachusetts.

Alongside such cultural institutions as MASS MoCA in North Adams and Tanglewood in Lenox, the Berkshire International Film Festival is held in great esteem, having celebrated the art of motion-picture making for its 9th consecutive year at the end of May with astounding fervor. Whittling down a selection of over 700 films from 18 countries, founder and director Kelly Vickery and her curating committee selected 75 independently released full-length feature, short, and documentary films to present this year. Such a growth in submissions complemented the growth of the donor pool, which, as chairman of the festival Al Togut mentioned on opening night, has now increased to over 400 donors. This is all to prove just how much the festival, with its dedication to promoting emerging filmmakers, is crucial in bringing a novel life to participating films.

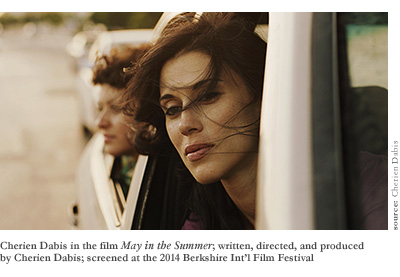

Among those for which a new existence has been created was the opening night feature May in the Summer (2013), presented here as an exclusive East Coast Premiere. It would be an understatement to say that the film—written and directed by Cherien Dabis, who gained recognition for her previous work Amreeka (2009)—is an exploration and depiction of an intercultural encounter. When New Yorker May Brennan, a role comfortably inhabited by Dabis herself, decides to have her wedding in her hometown of Amman, Jordan, tensions rise when her mother (played by Hiam Abbass) learns of the engagement and actively disapproves of her future son-in-law’s religious affiliation. With humor and sensitivity, the film contains an implacable sense of multiculturalism, not as some debated concept relegated to sociology or anthropology textbooks, but as lived experience. During the Q&A session following the film, Dabis illuminated the room with her presence, allowing the audience to get acquainted with the details of her own life that informed the film and filmmaking process. Born in Omaha, Nebraska, and traveling back and forth to the West Bank every summer to visit relatives, Dabis drew on “cultural shifts in perspective” as a theme in the film. She brilliantly etched a semi-autobiographical portrait, operating in front of the camera as actor and behind it as director—something akin to an ethnographer, “taking part in, and stepping outside to observe,” as she stated. For opening night, May in the Summer served as a rewarding selection, embracing a conceptual framework that reverberated throughout the festival as “international.”

Navigating the roster, the diversity of feature films and documentaries proved to be overwhelming. Like Dabis’ film, the documentary Faith Connections (2013) highlights greater cultural differences as filmmaker Pan Nalin travels to Kumbh Mela to explore questions of faith posed against a backdrop of severe diversity. In addition, the documentary Keep on Keepin’ on (2014), directed by Alan Hicks, pushes the boundaries of communication, revealing the narrative of 23-year-old blind piano prodigy Justin Kauflin, who befriends the aging jazz legend Clark Terry to overcome a consequential bout of stage fright. Hank and Asha (2013), a first feature from writer/director James E. Duff and tied for the festival’s Audience Award Winner, remarks on a new degree of stage fright—the online platform—when Asha, a film student studying in Prague, contacts director Hank in New York after seeing a screening of one of his documentaries at a local festival. In a witty exchange of video correspondences, both Hank and Asha simultaneously reveal their most intimate thoughts and feelings to each other while risking the relationship they’ve forged by actually meeting in person. Simulating the concentrated dose of romanticism once presented in films like Richard Linklater’s Before Sunrise (1995), Hank and Asha lent itself nicely in its Berkshire premiere this year, in both content and a form that challenged audiences to rethink motion picture production with its dependence on homemade video aesthetics.

In acknowledging newcomers like Duff and a host of others who have been working diligently to push their work, the festival presented its 5th annual Next Great Filmmaker Award in partnership with Berkshire Bank. The four short films chosen as finalists in the competition were a mixed bag, from complex narratives like If I Tell You (2014) by Brian Russell to immensely captivating animations like David Michael’s Moon Fishing (2013). What is impressive about the short film form is its condensation of both screen and story time, its insistence on how much can be told in so little. With this criteria in mind, Water Dogs (2013), written and directed by Matthew Slamowitz, won the award this year. The commonly-perceived hectic Manhattan assemblage of loud sounds and fleeting faces is deployed, when a disparaged homeless man happens upon a lottery ticket and, through a comical string of fortune, becomes a successful hot dog vendor. Slamowitz, who was in attendance for the brief ceremony, expressed sincere gratitude to the festival team for showcasing his work—a piece, he informed the audience, that took over a year and a half to complete and prepare for submission. A fifteen-minute short, a year and a half. This was a true testament to the profoundly assiduous personalities at the festival.

A fortuitous meeting at an event like this could propel the career of the most diffident artistic talent. It provides such an intimate experience for both the general public and filmmakers that any level of anonymity is virtually expunged. In a moment when I was mistaken for a cinematographer by simply offering to take a photograph of a couple sitting behind me with their iPhone, I realized this festival affords opportunities that could legitimize the position of anyone as a script supervisor, production assistant, a gaffer. With a history of furthering the careers of film crews worldwide (last year, the festival anticipated the 2014 Academy Award selections in presenting the winning films 12 Years A Slave and The Hunt), it also encourages the success of the less well-known. Many filmmakers will go on from here to enter their works at other festivals.

In addition to the enviable selection of films, the allure of the festival also resides in its location. The principal theaters employed—the Triplex Cinema and the Mahaiwe in Great Barrington as well as the Beacon Cinema in Pittsfield—simultaneously sculpted an environment of intellectual exchange and called attention to some of the venues’ charm. The last of a vanishing breed among larger cinema complexes that continue to pop up on the periphery, these movie houses are maintained by a close-knit community of ardent fans. And it was this passion and integrity, as represented in the bold shades of purple and crimson imbuing the cocktail party tents, that saturated every aspect of the festival. With an intensity made palpable for nearly 4,000 attendees this year, it is no wonder why the Berkshire International Film Festival received so much attention inside and outside the region. For at the intersection of travel between Boston and New York, it offers a unique scene situated along the Housatonic River, holding as much visual, cinematic pleasure as the films themselves.