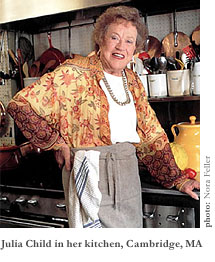

I was cooking dinner for my friend Cathrine recently when word came over the radio that Julia Child had died. Even though I knew she was very old (ninety-one) and that she had moved from her longtime home in Cambridge to an assisted living center in her home state of California, I was surprised at my own surprise and sadness. Improbably tall, exuberant, no-nonsense, down-to-earth, ubiquitous, and (my hunch is) exceedingly sane and happy, if anyone could outlive a life’s normal span, it was Julia Child. Still, ninety-one seemed a sweet enough reward for a life lived without regard to weight, cholesterol, low fat, high carb—low carb, high fat—or any of the other fads and diets that sweep our roots-starved culinary nation. Child practiced moderation in all things, a practice currently headed towards extinction.

While most people might think of Julia Child as the much parodied and loopy doyenne of cooking TV, those of us who actually prepare meals day-in/day-out know she was much more than that. Part of a distinguished lineage of American cookbook writers and food lovers, Child, like James Beard, M.F.K. Fisher, Marion Cunningham, and Alice Waters, mixed a thorough grounding in the fundamentals of cooking with an enthusiasm and appreciation for superb local ingredients. Child demystified French cooking—pulling it out of snobby (and no doubt mediocre) restaurant kitchens and bringing it into the home. According to Child, Americans could cook as well as anybody else and had no reason to feel second-class.

While most people might think of Julia Child as the much parodied and loopy doyenne of cooking TV, those of us who actually prepare meals day-in/day-out know she was much more than that. Part of a distinguished lineage of American cookbook writers and food lovers, Child, like James Beard, M.F.K. Fisher, Marion Cunningham, and Alice Waters, mixed a thorough grounding in the fundamentals of cooking with an enthusiasm and appreciation for superb local ingredients. Child demystified French cooking—pulling it out of snobby (and no doubt mediocre) restaurant kitchens and bringing it into the home. According to Child, Americans could cook as well as anybody else and had no reason to feel second-class.

My battered copies of Mastering the Art of French Cooking, Volumes I & II, (which she co-authored with Louisette Bertholle and Simone Beck) stand amidst my other cookbooks. I inherited them from my mother twenty-five years ago, along with her love of cooking and good food, and turn to them a few times a year—whenever I want to make a summertime soupe au pistou, cheese puffs, salade Niçoise, or the chocolate almond Reine de Saba cake. But more than the individual recipes, I know I can always turn to Child for technique. What’s the best cut of beef for a stew? What’s the most efficient way to cut a whole chicken into eight pieces? How do I hard-boil an egg without toughening it? Child’s instructions are detailed, precise, unworried, and encouraging. As she reassures her readers in the Forward to Volume I—”No out-of-the-ordinary ingredients are called for. In fact the book could well be titled ‘French Cooking from the American Supermarket,’ for the excellence of French cooking, and of good cooking in general, is due more to cooking technique than to anything else…anyone can cook in the French manner anywhere, with the right instruction.”

Child always decried food fads and diet crazes. But even as she was debunking the myth that only highly trained chefs could prepare French meals, rather than embrace her ideals at home in the kitchen, many Americans swung with the pendulum from canned and frozen foods and TV dinners to arcane, artisanal, gourmet delicacies. Self-proclaimed “foodies,” these folk search out the best “unknown” gelateria in Florence or the only authentic blue cheese maker in Vermont, without necessarily knowing how to roast a crisp but juicy chicken, mix up a simple vinaigrette, or choose a ripe cantaloupe from the supermarket mound. I suspect that Julia Child would be just as discouraged by the foodies as by the fast food and packaged dinner crowd.

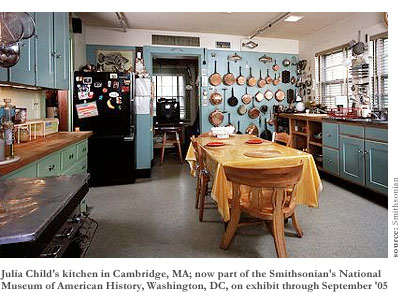

Child’s commonsensical love of all things delicious seems archaic in our current feast-or-famine climate where the bizarrely austere Atkins (yes, you may eat well-marbled steak and butter, but no, you may not eat a good, ripe peach?) competes with the snobby Slow Food movement. Also headed towards extinction, I fear, is a nation of home cooks. If my younger colleagues are any indication of trends, most Americans eat take-out on the run more often than they cook and sit down to dinner. And my high school students often write fondly of their weekly family dinner night. Why does it seem both fitting and depressing to hear that Julia Child’s Cambridge kitchen has been reinstalled at the Smithsonian—relegated to the past, a piece of museum history?

As I cooked, I listened to the various remembrances on the radio—Jacques Pepin, Todd English, visitors to the Smithsonian. I basted the barbecued beef brisket, sliced up red and green cabbage for coleslaw, steamed the home-grown green beans, mixed up the dough for sweet potato biscuits, and looked forward to Cathrine’s arrival. She came with reports of further tributes to Child she had read on the Internet. We sat down, sipped our beer, and ate. “What better place to be than here, eating a good home-cooked dinner the day Julia Child died?” Cat declared. What better compliment to receive from a friend? Jacques Pepin said that Child’s cookbooks will never go out of fashion or print. I hope he’s right.