Having written a few profiles of New England potters for ceramics magazines in recent years, I entered Our Cups Runneth Over, the exhibit at The Society of Arts and Crafts (SAC) through January 5th, with some anticipation. I wondered especially if I’d see work by any of the potters I’ve profiled—Judith Motzkin, maker of serene Zen teacups; Sarah Spademan, mass-producer of white novelty mugs with three-dimensional creatures inside; or Paul Heroux, creator of traditional Japanese oribe ware tea sets.

At the top of the carpeted stairs that took me from the SAC’s gift shop to the gallery, I glanced this way and that at the colorful ceramic vessels. The recent works of still-living clay artists, they’d been placed at immaculately precise intervals, each on its own little Plexiglas shelf, more or less at shoulder-level to allow maximum optical intimacy, on every available wall of the gallery’s two large wings. Alas, I spotted no immediate sign of Motzkin, Spademan, or Heroux work; but with one long pan of the place, I saw plenty of good stuff by a lot of potters I’d probably never heard of. Then I saw exhibition manager Margaret Pace DeBruin, who curated the exhibit with SAC director Beth Ann Gerstein, stepping out from behind a partition at one end of the gallery to offer her assistance.

At the top of the carpeted stairs that took me from the SAC’s gift shop to the gallery, I glanced this way and that at the colorful ceramic vessels. The recent works of still-living clay artists, they’d been placed at immaculately precise intervals, each on its own little Plexiglas shelf, more or less at shoulder-level to allow maximum optical intimacy, on every available wall of the gallery’s two large wings. Alas, I spotted no immediate sign of Motzkin, Spademan, or Heroux work; but with one long pan of the place, I saw plenty of good stuff by a lot of potters I’d probably never heard of. Then I saw exhibition manager Margaret Pace DeBruin, who curated the exhibit with SAC director Beth Ann Gerstein, stepping out from behind a partition at one end of the gallery to offer her assistance.

I didn’t think I needed much help—just the press release and the artists’ statements would be nice, thanks—but I did wonder how many artists had contributed to the exhibit and how the SAC had gone about selecting their work. “There are 51 artists in the show, from all over the country, plus two Canadians,” she answered, “and we selected the work by invitation only. You’ll notice that some of it’s functional and some of it sculptural; some limited edition, some production.”

Though the prices find their center of weight around $100 or so, many of the cups, especially the “production” pieces (those reproduced in large quantities for wide distribution), sell for under $50 per piece—affordable enough for holiday shopping by aspiring middle class standards—while some of the sculptural cups (comically difficult to drink from) go for as much as a thousand dollars a piece. DeBruin stressed that she has more cups in store than meet the eye, because as pieces are purchased—and I can say from eyewitness experience that they do get purchased at a rapid rate—they are replaced by others.

Starting my tour of the work on the walls, I walked in that trance-like, underwater way you do in a gallery where there’s a lot to look at and not much time to devote to each piece. Before long I was able to corroborate DeBruin’s implicit suggestion that the exhibit has a little bit of everything, something for everyone. It seemed that with every third, fourth, or fifth step I came across some whimsically decorated tumbler that put a kink in my otherwise fluid motion, syncopating my gait. It might have been one of the giddier objects, such as Irina Zaytceva-Freres’ porcelain mug, a tall piece rather garishly adorned with the face of a blue-eyed joker, his black-and-white-sleeved arm forming the handle; Michaelene Walsh’s earthenware Santa cup, a rosy-cheeked St. Nick mug (pun intended) capped with the legendary red stocking that features a certain white pom-pom, this piece a nod to kitschy holiday kitchen crockery; or Eunjung Park’s viscerally expressive sculptural cups, including one attached only as an afterthought to an eggplant handle at an untenable angle for drinking, and two other untamed animal cups (a pheasant and a chameleon) depicted with fierce nerve on a pair of pedestals, both likely to come alive, I was sure, to chase me down the stairs and back onto Newbury Street, where wild things in furs and leather jackets roam.

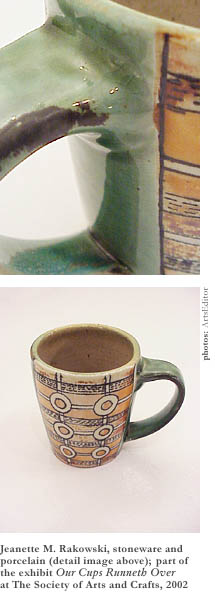

On the somewhat quieter side, the syncopating subject might have been Elisabeth Maurland’s white stoneware rabbit cup, two long-eared white wabbits (misspelling mine) on either side, face-to-face, upright on their hind legs as if in a mating dance, their eyes like wheels, background a blue jigsaw of geometrics (hexagonals, mainly?), the brim, base, and handle all a warm red—a cup you could really drink your java from. Or it may have been one of Jeanette Rakowski’s numerous contributions, accessible and useful tumblers prominently displayed in a row above the partition and crammed shoulder-to-shoulder on a shelf in the store room—all of them elegant and yet still earthy, glazed with symmetrical geometric designs or with figurative representations of green fish rising (on a white background bordered by black zigzag markings) toward the lips of the sipper.

On the somewhat quieter side, the syncopating subject might have been Elisabeth Maurland’s white stoneware rabbit cup, two long-eared white wabbits (misspelling mine) on either side, face-to-face, upright on their hind legs as if in a mating dance, their eyes like wheels, background a blue jigsaw of geometrics (hexagonals, mainly?), the brim, base, and handle all a warm red—a cup you could really drink your java from. Or it may have been one of Jeanette Rakowski’s numerous contributions, accessible and useful tumblers prominently displayed in a row above the partition and crammed shoulder-to-shoulder on a shelf in the store room—all of them elegant and yet still earthy, glazed with symmetrical geometric designs or with figurative representations of green fish rising (on a white background bordered by black zigzag markings) toward the lips of the sipper.

Admitting my preference for the earthy, modest ceramics style that owes its charm as much to Asian crafts traditions as it does to countercultural American attempts to find some footing in forgotten folkways, I appreciated (and generally do appreciate) these less ostentatious functional cups more than the sculptural cups. That’s why it was so easy for me to take to the third, unselfconsciously inconspicuous class of cups in this exhibition. I liked well enough Michael Corney’s Day of the Deadish skull mugs—kind of ghoulish, but better than those ghastly Toby mugs the Anglophiles like. But really (confessing a certain stodginess) I guess I preferred the porcelain faux-antique production pieces of Dale Mark—celadon tumblers in a number of rich colors (including copper red and pale green)—and not just because a nearby customer was oohing and ahhing about them. And, also on the simpler side, I really, really liked Chris Gustin’s lovingly lumpy pale green porcelain mug, irregularly large and nice to hold in the hand. (Note: here’s a gallery where you can actually pick things up!) Gustin’s work is as functional as can be, imprinted with the potter’s handiwork all over it, embedded in it even, his very spiritual essence, it may be, distilled in the form that you take your sips from. His trustworthy cups would probably bore a lot of people to tears—until begged to look at them closely.

As I took my solo-improv turn around the two wings of the gallery, I wondered if the title of the exhibit hadn’t been intended to celebrate the fountain-like source of creative energy that potters and other artists must find a way to tap—that inexhaustible aquifer from which the creative juices flow. I didn’t know if I’d like the taste of those creative juices, and winced at the association, thinking its taste probably more akin to bile than to a sweet Indian mango lassi. And I wondered which beverage would best suit the individual pieces—lemonade from a tall tumbler? Chamomile or mint from a teacup? I liked looking at it well enough, but couldn’t imagine drinking anything at all from Timothy Foss’ and Ursula Gullow’s mustard-yellow tumbler with the line-drawn impression of a chimp playing drums, or from Sue Katz’s porcelain birds’ nests (unglazed, beige, circular arrangements of clay coils big enough for wrens, swallows, and hummingbirds). I could, however, picture my morning coffee steaming in Barbara Knutson’s white stoneware fish cup—a pleasantly irregular and reassuringly heavy-bottomed mug with its own arrangement of vertical fish perched (pun unintended) on their tail fins, coming up toward the surface for a nibble at the toast crumbs; and I could see my bedtime herbal tea steaming in Friederike Rahn’s polychromed cup, a fish-scale pattern worked into the top blue section of the otherwise iron-red cup.

Somewhere along the line, I wondered why so much animal imagery appears in the figurative décor of ceramics work these days. Perhaps it’s part of the countercultural, anti-consumerist, utilitarian artist’s inclination to “animalize, vegetableize, and mineralize” herself or himself, as poet Galway Kinnell said he and his generation of “deep image” poets were trying to do during the 1960s and ’70s in their self-surrendering nature poems.

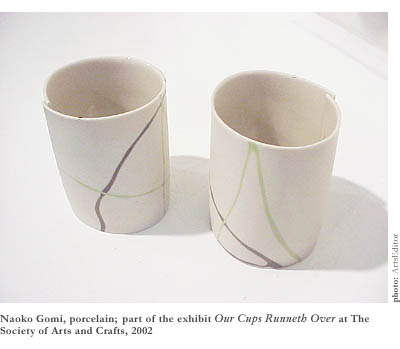

I glanced at Naoko Gomi’s inexpensive (at $35) porcelain cups, scattered modestly around the gallery, for an answer. I saw potential refuge from psychic distress in a slender cylinder quietly adorned by a delicate burst of five-petaled florets with raised yellow centers on an enamel-white surface, a cup made not by setting clay coils one on top of another but by rolling out a single slab of clay and sealing it irregularly along one side, so that it ends up looking more like a little vase than a drinking cup. I felt properly vegetableized by this cup, and also by two or three other pieces of Gomi’s—Meoto cups with large pink and small yellow bumps on the immaculate porcelain surface, likewise made of a single rolled slab of clay, likewise sealed loosely and irregularly on one side.

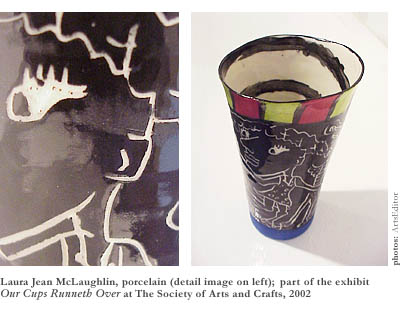

And then I stopped at another fanciful piece I wouldn’t necessarily want to drink from—Laura Jean McLaughlin’s wine glass, a porcelain representation of a little blonde girl in an orange scarf and red dress bearing a bulging basket of grapes, looking off somewhat forlornly, and balancing on her head the actual “cup”—a bowl, really, with horizontal black and blue stripes, a pagan image of Bacchus or someone inside (half classical drawing, half cartoon caricature), like much of the sculptural work, purposely disjointed for dissonant effect, juxtaposing three or more areas of contrasting surface decorations. At first I didn’t care for this piece—but then saw more of McLaughlin’s work on a shelf back in storage—including a tall black tumbler with a white line drawing of dogs, minotaurs, satyrs, etc.—and, again taking note of that hybrid of the classical and the cartoony, decided I wouldn’t mind it if someone were to give me one for my upcoming birthday.

I wasn’t twirling or prancing along the walls by this time—an hour and a half had gone by like that. I was back to walking in that underwater trance. And as I passed the windows overlooking Newbury Street at one end of the gallery, I got a pleasant surprise from the sight of a small, faceted, brown cup marked by a sort of calligraphic parabola in black on the side. I’d seen this serene and sturdy little Zen-master of a cup somewhere before. Wasn’t it—yes, it was!—one of Mark Shapiro’s? I’d written an article about an exhibit of his at the Lacoste Gallery in Concord last fall! I’d even visited him at his idyllic Western Mass. digs while six or seven of his best friends and apprentices came by to help load his kiln for one of his quarterly firings! I would have known that little teacup anywhere.